From the Who, to Hendrix and The Strokes - a history of the unrelenting high frequencies rock music has come to know and worship.

“Feedback is just an extraordinary sound, like an enormous plane. It’s a wonderful, optimistic sound.”

So said Pete Townshend of The Who, who incorporated feedback squeals and super-distortion into the band’s self-described “auto destruction” live sound in the mid ‘60s.

Read up on all the latest features and columns here.

But Neil Young permanently damaged his hearing while mixing his 1991 live album with Crazy Horse, Arc-Weld – a record comprised entirely of a sound collage of guitar noise and feedback.

“That’s why I really regret it,” he admitted. “I hurt my ears and they’ll never be the same again.”

The first record to use feedback was The Beatles’ ‘I Feel Fine‘, recorded in October 1964. During a playback during the Beatles For Sale album sessions, John Lennon leaned his Gibson J-160E – a semi-acoustic with a pickup to amplify – on Paul McCartney’s bass amp.

“It went, ‘Nnnnnnwahhhhh!” remembered McCartney, “We went, ‘What’s that? Voodoo!’ ‘No, it’s feedback.’ ‘Wow, it’s a great sound!’”

Lennon then asked Beatles producer George Martin if they could use it on a song he’d just written. In those days, any trace of feedback on a record suggested sloppiness on the part of a producer, but Martin loved new sounds, and OK’d it for the start of ‘I Feel Fine’, which went on to reach #1 in the UK and the US.

Lennon told Playboy in 1980, weeks before his assassination in New York City, “I defy anybody to find a record – unless it’s some old blues record in 1922 – that uses feedback that way” – ‘30s and’40s guitar pioneers like Willie Johnson, Johnny Watson and Link Wray had used the effect.

After The Beatles, feedback went on to feature on many British hits, including The Who’s ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere’ and ‘My Generation’, the latter gaining its effect by Townshend standing in front of his amp and vigorously shaking his guitar. Intentional feedback was part of Jeff Beck’s aggression arsenal, particularly on the solo on The Yardbirds’ February 1966 ‘Shapes Of Things’, mixed with Indian sitar drones.

Beck recalled using feedback:

“That came as an accident. We played larger venues, ’round about ’64-’65. And the PA was inadequate.

“So we cranked up the level and then found out that feedback would happen.

“I started using it because it was controllable, you could play tunes with it.”

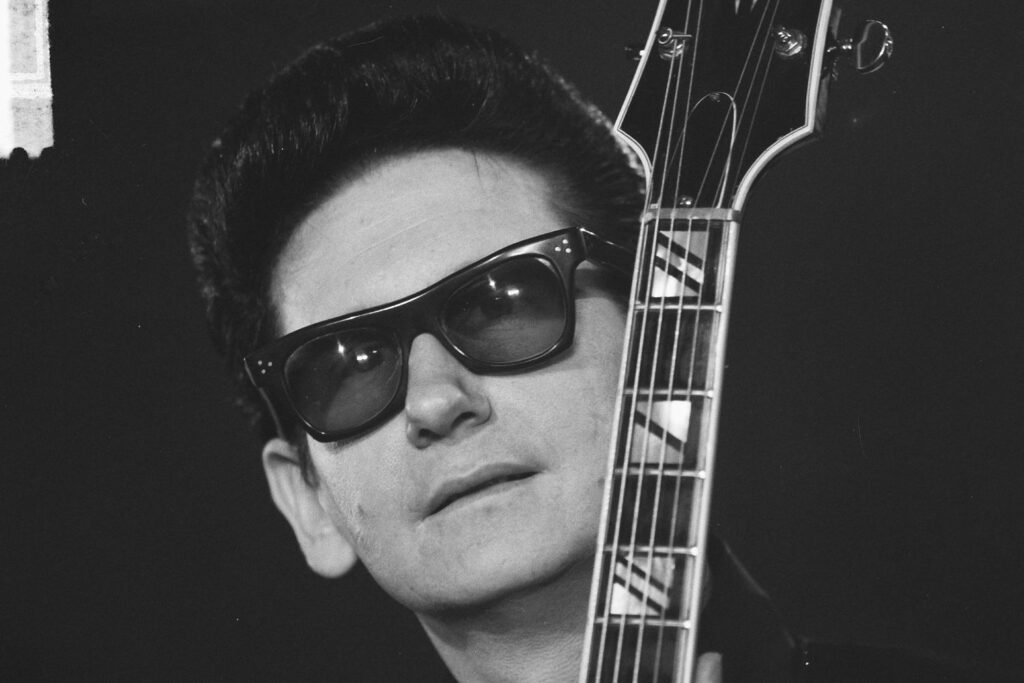

Jimi Hendrix got a more piercing effect by placing pickups closer to the strings than usual, got more sustain via a fuzz or overdrive pedal, and experimented with different types of pickups that all interact with feedback differently.

He used the effect on chart hits as ‘Foxy Lady’ and ‘Crosstown Traffic’.

But his most illustrious moments are on the soundtrack albums of two festivals, ‘Wild Thing’ from Monterey Pop (1967) after which he burned his guitar, and Woodstock (1969) during the American national anthem ‘Star Spangled Banner’ which he brilliantly turned into a sonic protest against the Vietnam war using his box of effects to denote sirens, helicopter blades and bombs falling on unarmed villages below.

Another good example of the use of feedback in rock music was Peter Green’s during his John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers days on ‘The Supernatural’ from the A Hard Road album.

The Missing Links, billed “Australia’s wildest group” in the 1960s, and banned from TV, were the first in this country to use feedback.

A report said of the Sydney outfit:

“On one occasion the squealing pitch of their guitars caused a mirrored ceiling to shatter and collapse into the audience.”

US bands Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead and Velvet Underground were also feedback aficionados.

The Dead dedicated a near-10 minutes on Aoxomoxo (1969) to the effect, called, what else, ‘Feedback’.

The 11-minute ‘Fried Hockey Boogie” from Canned Heat’s Boogie With Canned Heat (1968) featured another feedback ceremony from Henry Vestine during his solo.

It was one of the highlights of their live show, but entered folklore for another reason, more to do with their first singer Bob Hite, nicknamed “The Bear” because of his massive frame, who had a prodigious appetite for drugs.

According to Classic Rock, Hite overdosed frequently, onstage or backstage, and the band would continue their show nevertheless.

“Who can lift a 300-pound man?” drummer Adolfo “Fito” de la Parra shrugged to the magazine.

“Every other time, he’d wake up in the morning and say, ‘What the f— happened?’ … Er, you got wasted again.”

But on April 5, 1981, before a show at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood, a fan had slipped him a vial of heroin.

When Hite collapsed backstage before the second encore, Canned Heat returned to the stage and went into “Fried Hockey Boogie”.

Meanwhile, roadies were dragging him by his feet into a van to take him to Fito’s nearby home when his heart finally stopped as Vestine sparked into his blissful feedback orgasm.

King Crimson founder Robert Fripp’s guitar line on David Bowie’s “Heroes” (album version) is considered a standout use of feedback. His positioning of himself and his guitar at various points around the studio to record each note created the pitched, sustained feedback effect.

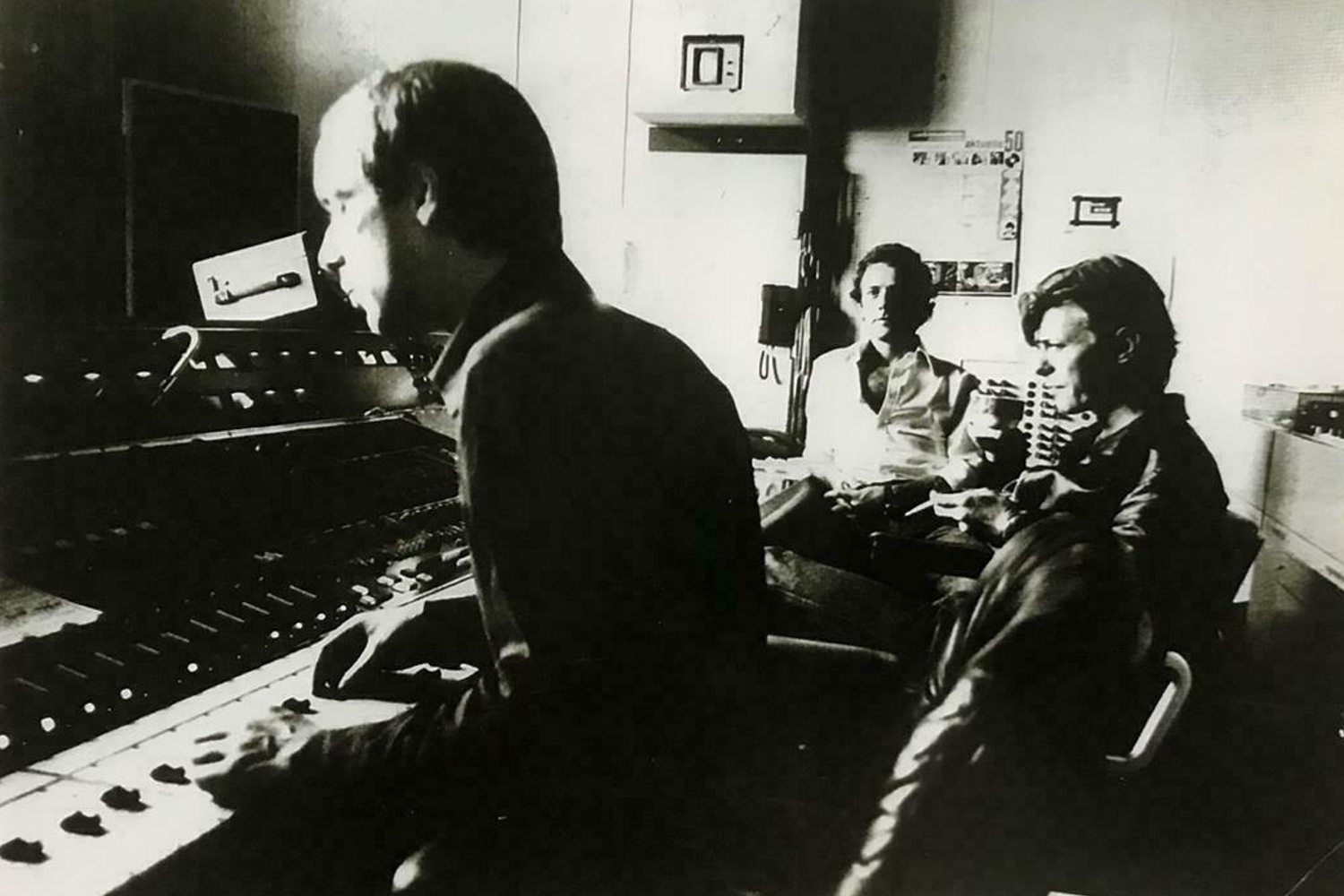

Bowie producer Tony Visconti recalled:

“Fripp had a technique in those days where he measured the distance between the guitar and the speaker where each note would feed back.

“For instance, an ‘A’ would feed back maybe at about four feet from the speaker, whereas a ‘G’ would feed back maybe three and a half feet from it.

“He had a strip that they would place on the floor, and when he was playing the note ‘F’ sharp he would stand on the strip’s ‘F’ sharp point and ‘F’ sharp would feed back better.

“He really worked this out to a fine science, and we were playing this at a terrific level in the studio, too.”

Readers interested in the art of feedback should check out Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music (1975), a double album of feedback loops fed at different speeds into two stereo channels. Even now, 47 years later, Metal Machine Music remains one of the most polarising records ever; a gorgeous electronic suite which later inspired noise and industrial music, or a piece of self-indulgent snot-gobble?

When it was first released, RCA Records saw it as an exciting opus and released it on stereo, quadraphonic vinyl and eight-track tape. Within three weeks, after it became the most returned release by the stores, they pulled it. Creem reviewed it with just the word “no” repeated, as in “nononononono” unceasingly.

Reed described it as “the perfect soundtrack to the Texas Chainsaw Massacre” and claimed to the BBC that many of the frequencies used were dangerous, and even illegal, to put on a record.

Some call MMM an extension of his feedback excursions with The Velvet Underground, while others query his state of mind at the time – he’d just gone through a divorce, was living with drag queen Candy Darling and injecting himself with speed due to exhaustion. To top it all off- he’d been hit in the face with a brick while performing in Europe.

Other commendable examples of feedback use include Nirvana’s ‘Radio Friendly Unit Shifter’, The Strokes’ ‘New York City Cops’ and ‘Reptilia’, Slayer’s ‘South of Heaven’, Midnight Juggernauts’ ‘Road to Recovery’, The Jesus and Mary Chain’s ‘Tumbledown’, ‘Catchfire’, ‘Teenage Lust’, ‘Sundown’, and ‘Frequency’, Meek is Murder’s ‘Sundowners’, At The Gates’ ‘The Flames of the End’, Weekend Nachos’ ‘Worthless’, Stone Roses’ ‘Waterfall’, Porno for Pyros’s ‘Tahitian Moon’, Tool’s ‘Stinkfist’ and ‘Jambi’, and Weezer’s ‘My Name Is Jonas’ and ‘Say It Ain’t So’.

Looking to learn more about feedback? Fender has you covered.