Who doesn't love them? Drum fills tips and tricks to make things interesting!

I thought, given it’s the education issue, that I would show you some cool drum fills. Warning however – it might get a little nerdy. If you don’t mind a little bit of technique and even a little math, read along! But who doesn’t love a good drum fill? Hopefully some of these are useful. I’ll also include some tips for extending these ideas later on if you want to nerd out a little more!

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

The background

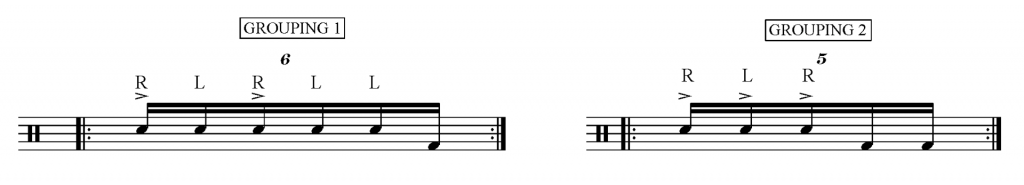

The notation shows two groupings or stickings. The first (A) is a group of six notes and features a combination of single strokes, double strokes, and a bass drum. It also features some accented notes. If you haven’t heard about accents on drums, the idea here is to play those particular notes with more emphasis (louder). You can also play the surrounding notes softer to bring out the accents. The bass drum however, can be whatever volume you like. The second grouping or sticking (B) differs slightly. Here we have a group of five notes and it features the similar technique of using accents but also a set of doubles on the bass drum.

All of the fills today are based around having R L R at the beginning of each grouping. It’s these notes that are best to move around the drums. In general, the accents are the ideal choice to move to the toms, cymbals etc. Experiment with this and see how the phrases change. For the purposes of this lesson, we’re going to execute the stickings over a 16th note (semiquaver) subdivision.

As semiquavers are based on even groupings of four notes, our two fills of six and five respectively, are going to ‘cross’ the bar and thus not fit perfectly in the bar. However, this is exactly why these fills are interesting. They will also sound less predictable too.

Grouping 1

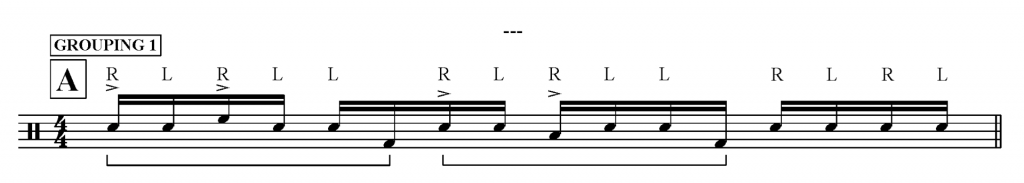

Figure A shows our first grouping over the context of one bar. You can see in this example that we can fit two of the groupings here. This leaves us with four notes remaining. I’ve left this as four single strokes, but you could make this whatever you want. Things get more interesting when we see the sticking over the context of two bars however (Figure B). Now, we can fit five groupings of six (told you it was nerdy) and we’re only left with two notes at the end of the bar. The cool thing here is not the fact that the groupings almost fit in the two bars but more the way the accents or emphasised notes fall in the bar. These accents really do create a unique motif and make for an interesting phrase or idea. I’ve notated how I might orchestrate the fill over the drum kit (using toms) but you can really experiment here and see what you like.

Grouping 2

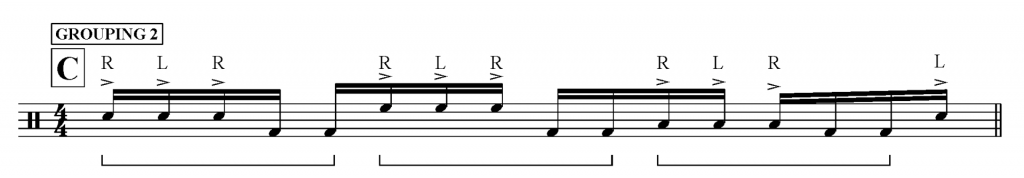

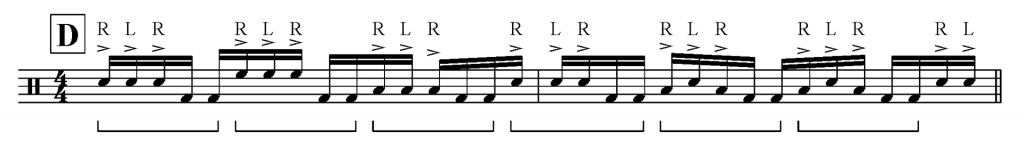

Figure C, or our second fill, steps things up a little. Now we are looking at using a grouping of five notes over our steady 16th note subdivision. The first example over one bar shows that we can fit three groups of five in the bar and only leaves one note remaining. Again, it almost fits perfectly but the accents and the bass drum separating the start of each grouping really do make it feel like an odd time fill. This is only exaggerated when we play the fill over two bars where you can fit six groups of five (Figure D). You can make it feel even more odd by being less predictable with where you place the accents. My example actually splits the main RLR sticking at the beginning of the grouping across the floor tom and the snare drum.

What else can I do?

Many of us learn a cool lick or idea but then only ever use it in one way. If the music we’re playing doesn’t match or suit how we’ve conceived and practised the cool fill, we often can’t play it. Both fills can be used over different subdivisions or feels. Try playing these over a triplet subdivision, for example. It’s a great idea to experiment with this and will make both fills more accessible when playing different genres of tempos. Additionally, the notation might seem overwhelming or look complicated. The important thing to remember is that no matter what part of the drumkit I’m playing, I’m still using the same sticking. The actual fill itself (hands and feet) don’t change. So, think of the sticking, not the notation.

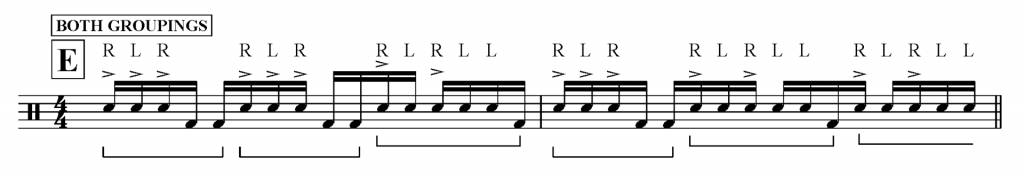

Some final ideas might include using a metronome to hear and feel the time while you’re in the middle of your sick fill. To take it to the next level, you could even try and mix and match the groupings! See the last notation figure (E) for one example of this – it’s one idea but you get the idea and maybe you can think of other combinations. Perhaps you can add a third grouping? Three notes? Four notes?

The educator in me cannot finish up without mentioning how important it is to pay attention to detail. When you’re playing these fills, listen to the sound coming back at you. Can you make the accents more pronounced? Can you lessen the volume of the non-accents (ghost notes)? Are the 16th notes steady and even over the bar? Are you staying in time with the click? All these questions are part of the process too! Good luck taking these ideas and experimenting with them. Don’t nerd out too much!

Check out this drum cover of Feel Good Inc., appropriately nicknamed ‘Fill Good Inc.’ in the comments.