A chat with musician, producer and film composer Tyler Bates about his work across some of the most iconic soundtracks in recent years - from 'X' to 'Pearl' and 'John Wick'.

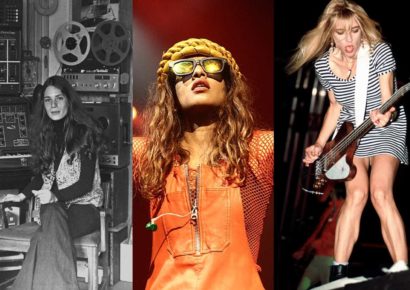

Tyler Bates regularly transitions from scoring some of the world’s biggest film and television franchises, from Guardians of the Galaxy to John Wick, to Ti West’s A24 X trilogy, to shredding for huge crowds as a rock musician, and back to the studio again writing and producing records with artists like HEALTH, Bush, In This Moment, and Starcrawler, to name a few. Ahead of the release of the highly anticipated fourth instalment of the John Wick franchise, John Wick 4, Tyler sat down with Mixdown to chat about his inspiration, workflow and the gear that supports his creation of mesmerising auditory images.

Just like many fantastic contemporary film and television composers, from Johnny Greenwood to Danny Elfman, you cut your teeth in the music industry playing in rock bands – would you say that this background has shaped, or manifested within your composition work in any way?

Undoubtedly so. I think all of my life experiences have had a significant impact on my conceptual mind and sensibilities as an artist. I love music of all genres and cultures but I have not experienced anything that satisfies me the way writing and performing rock music does. I can say the same about scoring movies, television shows, and video games; they also have an allure that I can’t deny. I have worked very hard to have the opportunity to explore my interests and capabilities in every facet of music both as a commissioned artist and sometimes simply for myself.

Before you began working in the field, what was your relationship to film/audiovisual media like? Have you always perceived a synesthetic connection between image and sound?

I have always had what I now know is synesthesia. It’s not as though I’m walking through life on an acid trip (lol) but I definitely relate to musical motifs and modalities in terms of colour more so than analysing what I hear in technical terms. My film composition career began in the nineties when a producer asked me to write several “rock” cues for a low-budget film. That opportunity led to the next and before I knew it I scored eighteen films by the time I met another person who had ever scored a film. I am grateful that the directors, editors, producers, dubbing mixers, and post – supervisors shared their insights with me to help educate me on the filmmaking process so that I could succeed at my task. It took a while before I found my voice in my film work similar to the way I recognise my signature as a songwriter or as a guitarist.

The breadth of your work is really remarkable. Where do you typically glean inspiration from at the beginning of a project? Could you walk us through your creative/production process from the commissioning of a score to its delivery?

This question alone could be a semester-long masterclass at a university! Inspiration comes from a combination of the material or subject matter, the director’s sensibilities, topical/cultural research, and any other information I can learn about the project at hand. My conceptual approach begins there but I factor my resources and timeframe into determining what I think I can accomplish within the limitations of those parameters.

Looking back on my career I think that my best work is a byproduct of effective communication and a director’s trust in my ability to be inventive within the scope of their sensibilities and to serve the needs of the picture; this can be a grand gesture or it can be a subtle melody or textural motif; whatever the picture calls for is the job at its core. The timbre of a voice, or the characteristics of how an actor moves or gestures are determining factors in the choices I make when writing for a picture.

I try to approach each day of my life with the intention of being a potent creative collaborator while learning something new about people, culture, music, and technology among other things. The longer I’m on Earth, the more I know what I don’t know. And this thought never ceases to fire me up to see what I am capable of creating or accomplishing. I need to do this for myself in order to be of valuable service to others. I have learned countless lessons from my failures and mistakes which has helped me become a better artist and collaborator and see my objectives more clearly. I’m not sure if this answer is useful but it’s the best I’ve got at the moment.

Could you talk a little bit about your typical workflow/set up? How does your process differ across the multiple medias you compose for, from film, to video games to TV?

On any given day I am working on a movie, a tv show, and songs or an artist album. It’s challenging to shift gears from one medium to the next but this also keeps my mind fertile with inspiration. I have to dedicate several hour blocks to each project I work on each day in order to get deep into the creative process necessary to create quality work. Some days are more potent than others but even if everything I write one day is trash I usually experience a positive residual effect the following day after my subconscious mind has done its thing. Sometimes jumping from writing a score cue for a film will open me up to fixing an issue with a song if it’s not coming together the way I want it to.

Logistically speaking, I have two associates that work with me at my studio and each has their own room fully equipped with computers and instruments. We are networked so sharing sessions and transferring data between us is fluid and easy. For instance, we record live drums and percussion that might require some editing or pre-mixing as a time-saving measure given that a film or television composer’s work is done in a race against time. Each day as soon as our rigs are booted up, the hourglass is tipped and we are working as quickly and efficiently as possible in order to meet daily or weekly deadlines. It can be pretty intense!

Our primary DAW is ProTools because it’s the platform on which all film and television projects are mixed and I think the editing and mixing capabilities serve my approach to creating and producing the best of any platform I have worked on. During the course of scoring a large-scale movie (for instance John Wick 4) the picture edit is continuously evolving so in turn, I receive countless versions of each reel from start to finish of scoring a film, to which I then conform my works in progress to match the latest picture edit. This process requires the composer to share files and sessions with guest musicians (colourists) and music editors, who most commonly work in ProTools. Typically, music editors have access to the most up-to-date picture as well as being privy to knowing firsthand how the music is working for the director. It can be helpful for a music editor to share their work with me so that I can see exactly what adjustments they might make to satisfy a director’s request. This helps the composer more clearly understand a director’s sensibilities when they are unavailable to speak on the phone.

We also use Logic and Ableton, and anything that is useful in creating any given score. I experiment a lot playing my Togaman Guitarviol through guitar pedals. My love for pedals has become both an expansive and expensive obsession! lol. Through the years, Wolfgang Matthes, my long-time collaborator in modular synth experiments and sound development, has worked with me to create unique banks of sounds for each film, television, game, and album project, that I have done over the past couple of decades and then some. I introduce concepts that I think are interesting sonic ideas to pursue and then once we’ve had several experimental sessions Wolfy formats the fruits of our labor if you will, into sounds that are hosted on the Logic EXS24 sampler. Usually, 25-30% of the sounds we create end up in the project they were intended for but they almost always find a purpose somewhere down the line. I prefer the EXS24 to other sample playback platforms because it is the most intuitive to the way my mind works. Kontakt, please check out the amp envelope on the EXS24!

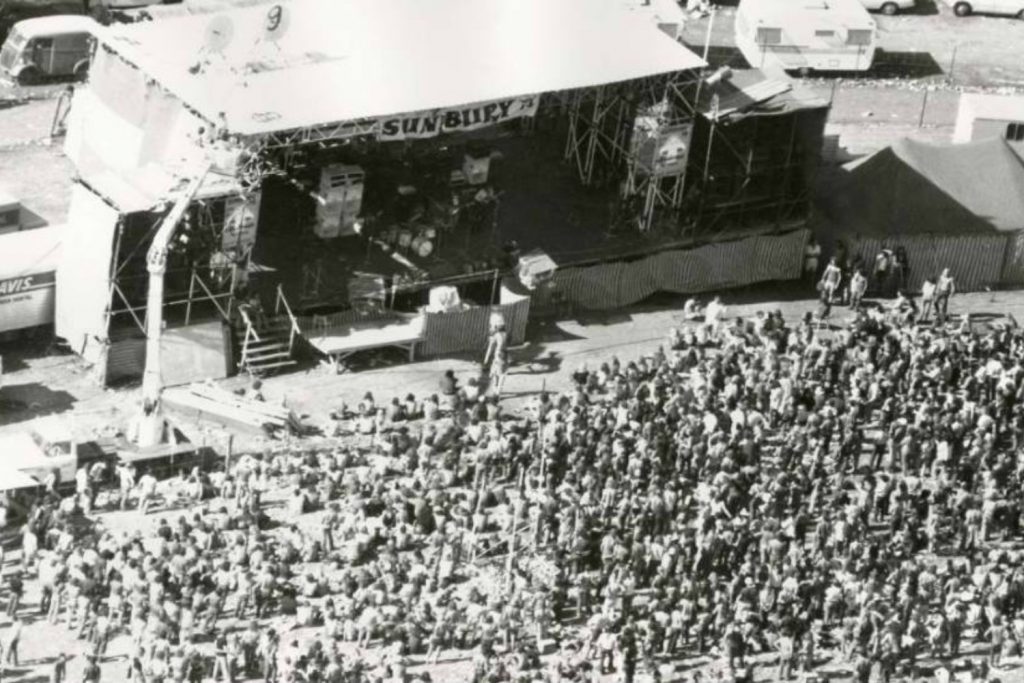

Here at Mixdown we’re huge fans of your work across Ti West’s two most recent films X and Pearl. Both are highly referential, celebrating iconic periods of cinematic history and the art of image making itself. Both of the films’ scores have a huge hand in this compelling conjuring of the past, from Pearl’s lush orchestral swells and frenetic strings that harken back to Hollywood greats like Les Baxter and Bernard Herrman, to X’s homages to 70s grindhouse and pulp horror spooks. Did composing for these two films require a lot of research?

X was the first of the two aforementioned films. We discussed music and movies that might inspire the concept for the score to X, all of which we are both familiar with. I started working on that film just as Chelsea Wolfe and I finished collaborating on a track for the Dark Nights Death Metal album. Ti and I were already discussing the idea of an avante-gard “vocal-centric” score woven into a murky atmosphere with unsettling percussive hits and frequencies that heterodyne to create an unsettling environment. Around the time that Ti and I agreed on a creative direction Chelsea expressed her interest to work on a film score. I introduced her to Ti and we started working from there. It was a great experience working with Chelsea and her creative partner Ben Chisholm. They are both excellent people and great artists.

Pearl was shot immediately after X, so by the time we delivered the final score for X, A24 told us that they wanted to release both films within months of one another, which is extremely rare for a director. It also meant that Pearl, the score for Pearl needed to be written, produced, and delivered in just over two months. That is very little time for a score of that ilk. I told Ti that in order to complete the score in time I would need to work with Tim Williams, a long-time collaborator and dear friend of mine. Tim and I share a love for the great scores from the golden era of Hollywood. Besides John Williams’ score for Star Wars and John Carpenter’s score for Halloween, I would have to say that Bernard Herrmann, Ennio Morricone, and Maurice Jarre, were the first film composers that I became familiar with by name. Tim has a classical piano background, which has made for some interesting colabs between us through the years, most recently, Netflix’s Agent Elvis adult-themed animated series.

The sonic world you have built over the course of the John Wick Franchise is integral to the tone of the films. Being known for their action sequences, do you find that you have certain compositional tendencies that you fall back on to translate that magnetic sense of tension and release?

The sound of John Wick was created by Joel Richard and me, starting with the first instalment of the franchise before it entered the pop culture zeitgeist. It’s truly amazing that it has grown into what it has become since its inception. Joel and I are long-time friends and we share similar tastes in a vast amount of music so our JW collaboration is essentially a musical conversation. Once we familiarised ourselves with the martial arts culture in the context of what I consider to be a graphic novel-type film, we were encouraged by directors Chad Stihelski and David Leitch to experiment and bring the rock! For Joel and me that was a dream assignment. Again, we are experimenting with synthesizers and playing guitars. Super fun! I’m grateful to have written and produced the majority of the songs with many great artists for this franchise.

What has changed and what has remained the same across the four John Wick film scores? Are there any consistent motifs that you deem indispensable to the narrative world?

The John Wick theme is pervasive throughout all four films. It’s pretty awesome when it drops and we feel the theme land in undeniable John Wick fashion. We have expanded the genres and cultures from which the Wick score is inspired by just as the franchise has traveled to many locations around the globe. This has created the opportunity for Joel and me to bend genres while keeping the crux of the John Wick attitude front and centre in each film. John Wick 4 is pretty much the Mt. Kilimanjaro of hybrid film scores. It is a massive amount of music. And even though this score contains orchestral passages, at its core JW4 is still a hybrid score, which in my experience, developing and producing this music and keeping the ball in the air, is extremely challenging, especially for an action movie where there are twists and turns every minute of the film.

I love that Le Castlevania has created great tracks for club sequences for the entire JW franchise. He too is a dear friend, so I was particularly stoked when I heard his “John Wick Mode” track blasting at a Raiders home game at Allegiant stadium. It was awesome to see NFL fans getting pumped up by our friend’s music. They all know John Wick. That’s pretty cool!

To wrap things up, I’d love to hear a little bit about the collaboration you’ve embarked upon with your daughter Lola for the John Wick 4 soundtrack.

Lola Colette once was my young daughter but now she’s a formidable artist with whom I collaborate in many musical situations. Through the years I have hired her to play piano and sing on my scores, and I have also worked with her to produce her music together in the studio. She has trained to be an incredibly self-sufficient musician and a real Swiss Army Knife vocalist. Lola became involved in John Wick 4 because she was on tour as the opening act for Jerry Cantrell’s ‘Brighten’ tour when Chad Stihelski asked that I demo up a couple of classic songs in the John Wick aesthetic to be considered for inclusion in the film.

I was on tour playing guitar with Jerry at the time, so I set up a recording session on a day off. I asked Lola if she wouldn’t mind singing a demo vocal for me so she listened to the song a few times and cut it live in the room with all of us in the band. I was honestly surprised by how fresh she sounded singing the song. I sent the scratch demo to Chad and he put it in the cut of the movie. It stayed as it was for six months before it was time to cut the final version for the film. When I asked what he wanted to do about the vocalist for ‘Nowhere to Run,’ he said he liked Lola’s voice and wanted her to sing the final version for the movie. Sam and Nick Wilkerson from the band White Reaper were touring with Lola at the time, are the rhythm section on that track. Sophie Negrini sang backing vocals with Lola, and I played the guitars. It kinda just happened naturally.

Over the years, I have asked Lola to sing on many projects because she has an innate sensibility about what is appropriate as far as performance and arrangement. It’s my obligation to bring the most appropriate artists and musicians to contribute their talent to whatever commissioned work I am doing. I have grown immensely through the many collaborators who have helped me to craft the many movies, tv shows, games, and records I have had the good fortune to work on over the years. There is literally not a day of my life that I don’t work with a brilliant and talented artist that in turn inspires me to grow. I cannot thank each and every one of them enough for their selfless contributions to my work. But to each and every one of them, thank you!

Keep up to date with Tyler Bates here.