We chat with studios and engineers to discover how their approach to work has shifted since COVID-19.

It is no secret that COVID-19 flipped the music industry upside down and even through lockdowns and vaccines, the outlook is not much brighter more than a year on.

With performing, touring, and meet and greets cancelled or plunged into uncertainty, musicians and fans alike suffered indescribably.

Read all the latest features, interviews and columns here.

As the pandemic and forced closures of music venues, pubs, and bars halted artists’ ability to do what they love, the employees behind those sites were just as affected, if not more.

Whether they are checking tickets at the door, serving drinks behind the bar, or showing you where your seat is, so many unsung heroes of live entertainment had to adjust to the pandemic, or lost their jobs.

But before an artist reaches these venues to play tracks off their new album, fans need to consume the music which needs to also have been released, which of course needs to first be recorded.

More than 155 million albums were bought or streamed during 2020 which puts a lot more employees behind the music such as engineers, producers, and studio employees.

A recording session before the pandemic could have looked very different for a lot of people.

Many bands and artists with record label backing could have spent a month or two in a studio refining their songs with a producer and an engineer, or even many of them, while others could have sat with an engineer and recorded their decidedly perfected parts to be mixed.

A lot of it depended on finances and time, but the pandemic forced many people’s hands as recording studios became out of favour with their heightened health risk and of course, their closure.

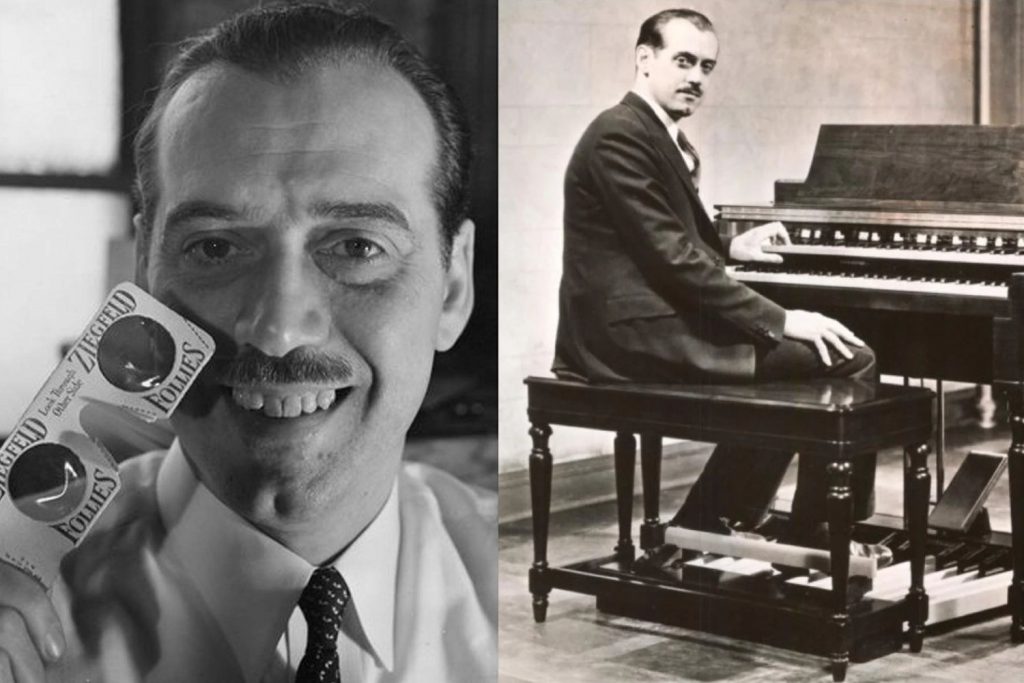

Located in South Yarra, Australian recording mainstays Sing Sing Studios boast an extraordinary range of clients such as INXS, The Living End, The Temper Trap, Nick Cave and Kylie Minogue, with the likes of James Reyne, The Avalanches and Julia Stone frequenting the studio more recently.

With the pandemic rearing its head last year, the world-renowned studio was forced to return band deposits and halt further plans.

Being granted permits to complete mixing for The Masked Singer recordings, Managing Director Kaj Dahlstrom said their reputation helped with their business through the enduring lockdowns.

“Some bands returned, and some didn’t,” he said.

“We’re pretty lucky because we’re sort of fairly known so we do get the television work and things like that, but it was a tough year for sure.”

The essential work the studio was able to complete included the thorough cleaning of equipment between touches, compulsory face masks for those not singing, and of course the social distancing.

Mr Dahlstrom said with the new health directions and COVID normal we are adjusting to they have been forced to turn things down.

“We’ve got a large place, so we send (people) out there because you need a space to separate people and we try to divide things up so that sessions are not too big,” he said.

“If it’s too big, we turn them down.

“It’s too risky at the moment because if something happens they’ll shut the whole studio down”.

Sing Sing operates entirely with freelance engineers who are familiar with the space and its setup, but when the studio was shut and people needed to record, freelance engineers suddenly found themselves to be more in demand than ever before.

James Millar of MillAttack Music is a freelance sound engineer who specialises in mixing and has worked with Robbie Williams, Tina Arena, Client Liaison and more.

He said his ability to work did not change too much through COVID, but the way he worked with bands and artists did.

“Even before COVID, I didn’t often have people wanting to do sit-ins so that wasn’t so much of a problem,” he said.

“(The problem) was more so getting together to do the last five per cent or even just discuss upcoming projects, it took a little bit of getting used to moving all that online”.

“It’s much quicker to make a few changes with someone sitting next to you than it is trying to follow a list of instructions on an email”.

Freelancing in any career carries its pros and cons. As a sound engineer, it allows Millar and others to structure their days and workflow, but it also means that work is not guaranteed.

Millar said working in a studio “would be more structured and things are coming to you, whereas, as a freelancer you’re trying to find the work as well, bring it in, and do the actual work on top of that”.

While the pandemic has not significantly impacted his business, he thinks the other side of this pandemic may look a little different in terms of attitudes towards freelancing.

“There’s maybe been a little bit of a shift, people I think are a little more open to it than maybe they used to be”.

Despite the hiccups caused within the recording industry, music was and still is being released.

For many big artists, finding ways to soldier on may not have been as big an ask as some less established bands and artists.

With the boom in sales in music and audio recording equipment, people were finding ways to adapt to record music.

As Paul Kelly released songs made during lockdown and Billie Joe Armstrong sung about isolation, bands and artists were still trying to work through the final touches of their albums.

Many bands did not have the luxury of a World War Two bunker-turned-recording-studio like The Rubens did, leading to acts – even those as legendary as Crowded House – being forced to finish recording their albums in isolation.

“We were in LA together, but we were still working in our individual little pods: sending files and doing Zoom calls,” Neil Finn said.

For albums recorded before the pandemic, groups like The Avalanches were forced to halt their album release due to vinyl and CD manufacturing plants in America shutting down, while Bring Me the Horizon experimented with split releases between their digital and physical copies, ultimately resulting in a number one album when the physical copies were released.

As Australia’s COVID control keeps improving and moving forward, Mr Dahlstrom said getting into recording studios is still worthwhile.

“The bigger studios have a lot of equipment, so you get a lot of colour within the music,” he said.

“With microphones, guitars, keyboards, grand pianos, and Hammond organs and things like that which a lot of home studios don’t really have”.

The aesthetic and practical setup of studios also provide opportunities for filming to promote music, but Mr Dahlstrom said the sonic quality should not take priority in a song’s release.

“But it’s all about the song really, it doesn’t matter how well it’s recorded it doesn’t make it a hit, the song is what matters the most,” he said.

View this post on Instagram

Learn all the most important audio buzzwords to up your studio knowledge here.