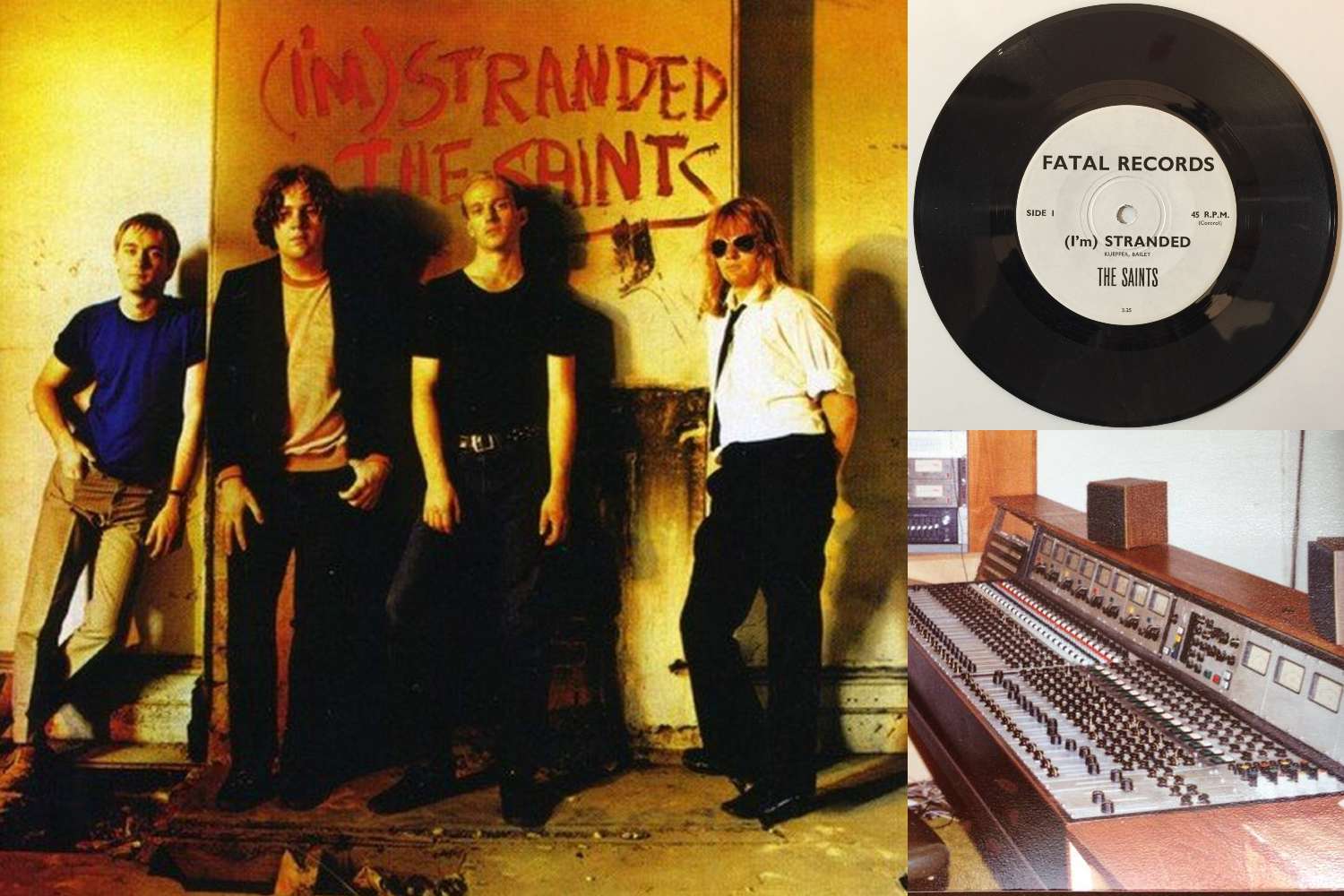

The making of The Saints' '(I'm) Stranded' from its uniting social alienation message, through to the lost mixing console

Forty-six years after it was made, ‘(I’m) Stranded’ still delivers that blitzkrieg punch which caused a global revolution back then.

Social alienation wasn’t just in the lyrics, it permeated throughout the whole record.

The melody came to Ed Kuepper during a lonely midnight train ride in April 1974 from Brisbane city to his parents’ place in the suburbs.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

The guitarist honed the melody and first verse in his bedroom, and then gave it to singer Chris Bailey – a fellow social isolationist who wore army jackets adorned with anarchy badges and whom he’d met at school detention for both refusing to cut their hair – to come up with the rest.

A crowd pleaser

The early incarnation was slower and rambling with more verses, and stretching to five minutes.

“The first time we played it in front of an audience the response was like everything else we did – pretty good,” Kuepper laughs.

“The people who liked us loved everything we did. The people who hated us hated everything we did.

“I don’t think there was a halfway point. It was either right on or right off!”

An irate neighbour threw a brick through a window of one of their rehearsal places on the corner of Petrie Terrace and Milton Road.

When they turned it into an ad hoc venue, they made the mistake of painting Club 76 outside.

That alerted the cops stationed opposite, who hassled the band endlessly about the building’s lack of safety, overcrowding, and violence.

Clubs wouldn’t have them so they booked their own gigs, even in RSL clubs which confiscated their bonds because of the mess left behind.

The late great Chris Bailey’s 1997 liner notes: “We spent a lot of time in bedrooms (wasted at least carnally!) garages and church halls making a loud racket – as young men with noisy toys want to do!”

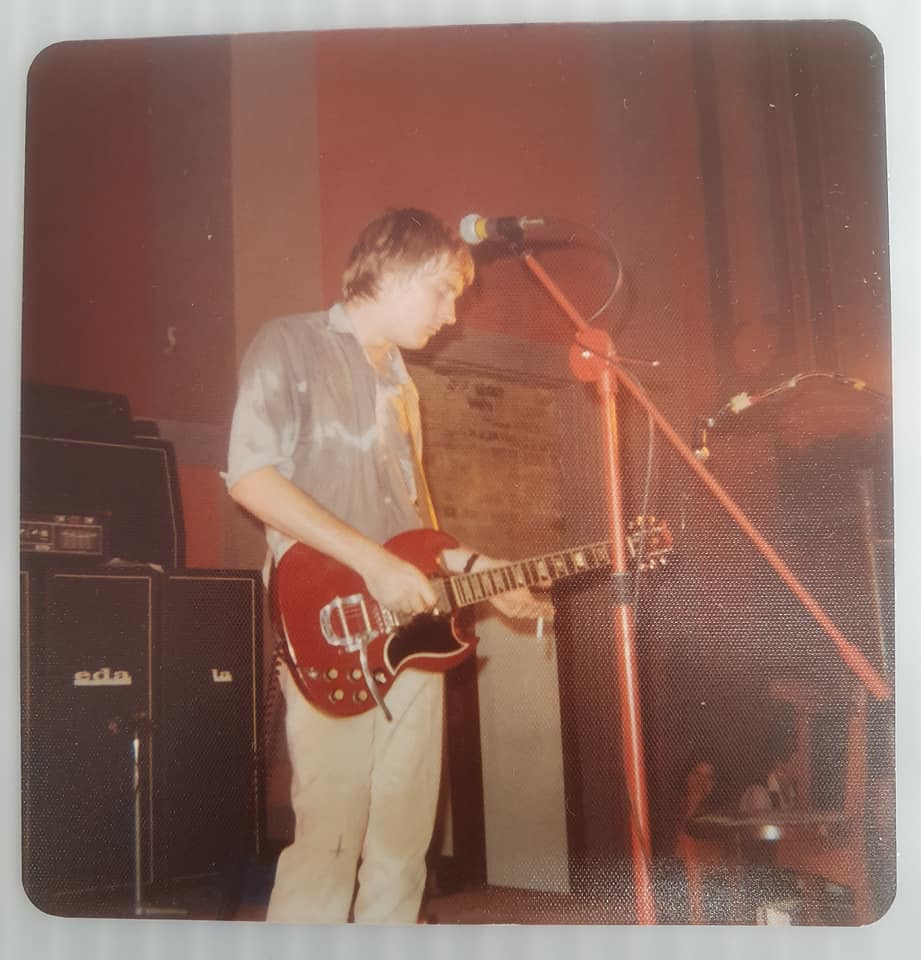

The gear

The song was written on Kuepper’s Hofner Club 40, which his folks got him when he was nine.

But for the single, it was the 1962 SG Standard, which wasn’t cheap, but it was his guitar goal.

“I think three of the four first records that I bought featured an SG prominently (Paranoid – Black Sabbath, Live at Leeds – The Who, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! – The Rolling Stones) so I thought ‘I’ve got to get some of that sound’! I think the body is very comfortable, very sleek, they’re not too heavy, they have a nice way of taking off if you’re playing really loud.”

From the mail order World Record Club, he was introduced to the Stooges, New York Dolls, and Miles Davis, while his mother had a penchant for Elvis Presley and Hank Williams.

The SG was 12 years old when Kuepper got it for $420, which was seven weeks’ wages of the $65 he earned as a storeman at Astor Records.

“It was a great guitar. Then it got stolen, so I got a Fender Stratocaster to get a different sound.”

Kuepper was experimenting with guitar tunings at the time and ‘(I’m) Stranded’s slowly shifted.

For the recording of their first single, The Saints didn’t think ‘(I’m) Stranded’ necessarily stood out on their set-list.

But a straw poll with their 50-strong following voted overwhelmingly for it.

The Saints existed in their own bubble. They didn’t know anyone in the music industry… or other musicians… or where a studio was.

Drummer Ivor Hay worked in a tape duplication shop, and workmates assured him that Brisbane recording pioneer Bruce Window’s Window Recording Studios in Buchanan St in the West End charged decent rates.

Recording and mixing ‘(I’m) Stranded’ and its b-side ‘No Time’ took five hours for a total of $250 (or roughly $1,653.30 in today’s money).

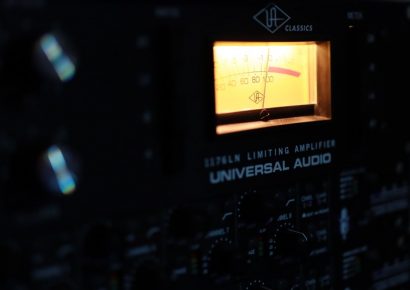

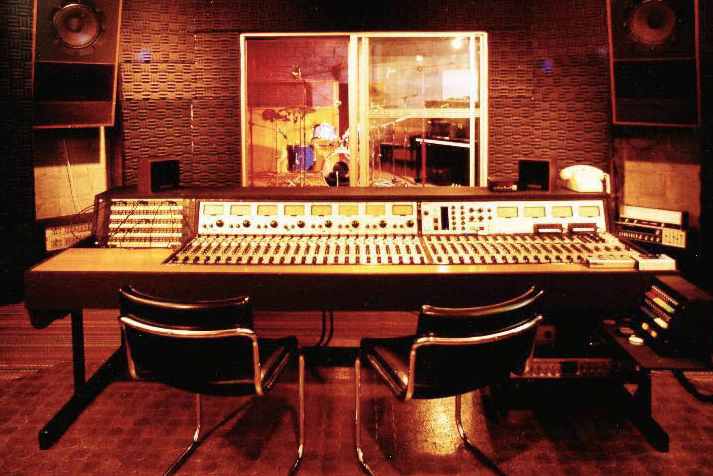

Window Studio set up

Window Studio’s console was built by Bruce Window, configured with 24 mic input channels and a 16-channel monitor section.

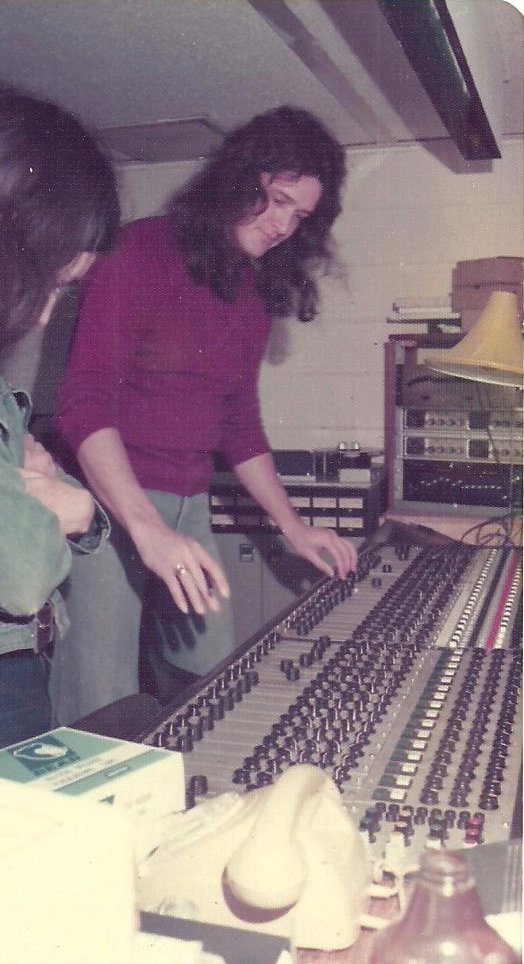

“It was quite large for its time,” according to Mark Moffatt, who as a 25-year old worked there as a house engineer on tracks and jingles in between playing guitar for the Carol Lloyd Band.

“Each channel had a high quality input transformer and old style passive equaliser technology resulting in a very full sound and still highly desirable these days in vintage consoles.

“The console had been through the ’74 Brisbane flood and after cleaning it functioned well which speaks to the quality of construction.”

Tape machines

The multitrack was on an Ampex MM1100, 16 tracks on two inch tape.

The mixdown machines were Revox and Rola.

Outboard gear

“Very minimal, there was a spring reverb unit, again built by Bruce, a Countryman phase shifter, and four of the fabled Pye compressors which these days are bringing upwards of $10k each.”

Microphones

“To his credit Bruce had assembled a great collection of high end mics especially for a small studio at that time.”

Drums

Kick: AKG D12

Snare: AKG D190

Hihat: AKG C451

Overheads: 2x Bang and Olufsen BM6

Toms: AKG D190

Bass: Custom BWE direct box.

Guitar: (close) AKG D202 (distant) Neumann U87

Vocal: Neumann U87

“Bruce’s family and friends were thrilled when the studio was included in the Mixdown’s 10 Most Important Australian Recording Studios of the 20th Century list, as was I.”

The session

Kuepper, Bailey, Hay, bassist Kym Bradshaw, and girlfriends, met at the studio in the late evening in June.

Before Phil Spector began working with The Ramones on End Of The Century, he asked them, “Do you guys wanna be great or good? ‘Cause I’ll make you great.”

That didn’t happen with The Saints and Moffatt. They had never heard of each other until then.

But Moffatt had just returned from London (he worked at guitar shop Top Gear Music, where Jimmy Page and Eric Clapton would wander in for a cup of tea) and had seen its pub-rock and punk scene emerge in its sweaty dives.

“Window was just a control room and one recording room measuring about 25’x25’ which was not very big,” Moffatt says. “So this meant using baffles on the drums and guitar amp.

“The drums were always in the back left hand corner, Ed was set up as far away from the drums as possible, in the opposite corner which was also close to the door and also meant I could run a mic cable out into the hallway.”

“A big part of the ‘wall of sound’ everyone talks about on ‘(I’m) Stranded’ and ‘No Time’ was the mic I put out in the concrete hallway for Ed’s doubled parts.

“I had learned about distant miking from Clive Shakespeare who produced the Carol Lloyd Band album at EMI in Sydney and I found the hallway at Window perfect for that technique.

“Fortunately most sessions I used it on were at night as the hallway served the front office and tech workshop.”

Essentially the two tracks were to be reproduced as they were played live.

“The guitar, tuned up two semi-tones, was recorded straight into the amp, with no pedals on either track,” Kuepper says.

The Saints took their ‘us against the world’ attitude into the studio. But Moffatt was friendly and business-like enough for them to agree when he suggested some changes.

These included Bailey doubling the vocals in the chorus and Kuepper doubling his guitar.

Moffatt also recommended Kuepper use his 1960 Fender Super amp rather than his Golden Tone.

But the two men now disagree on if that affected the sound on the two tracks.

Kuepper: “I don’t think so. My Golden Tone would have distorted a little earlier, so the sound was cleaner, which I think suits it.

“It gives it a bit more definition, a little more presence.”

Moffatt: “Most definitely. Ed’s amp was way too clean so I had him try the ’60 Fender Super I had brought back from London.

“It was a tremendous amp, the speakers were on the verge of blowing and it had a replacement output transformer from a Marshall, an unusual combination which gave it a loud angry growl when turned up full.

“Ed plugged straight in (no pedals, contrary to urban myth) and there was the sound, his powerful right hand and that amp. Not much else was said as it was clearly better for the recording than his amp.

“Thinking back, that was the point when it all came together, it was a great sound which Ed seemed to enjoy because he really dug in and played off it.

“I remember he broke a number of bottom E strings that night which says a lot about the power in his right hand.

“When Rod Coe from EMI came up to produce the rest of the album, myself and my amp were on tour with the Carol Lloyd Band so the remaining album tracks sound quite different.

“I sold the amp on moving to the US so it’s out there somewhere in Australia, easily identifiable as it had a blue jewel light, Fender tilt legs fitted and a Top Gear London sticker inside.”

For The Saints, hearing their music properly recorded than on cassette was an eye-opener.

Moffatt: “I remember when the band came into the control room to hear the first playback one of the girlfriends saying, ‘It sounds like a record!’ or something similar.

“The guys were happy with what they heard and we got on with the next track and overdubs including a bit of rock and roll piano at the end of ‘No Time’, I think that was Chris.

“Personally I think ‘No Time’ has a more powerful guitar sound and performance but ‘Stranded’ made a better connection as a song.”

The session finished around midnight. Three of them had day jobs to start in the morning so they split for home immediately after.

Bradshaw worked at the tax office, Bailey was on the dole, and Kuepper went on to work at the Dept. of Aboriginal Affairs for $100 a week, and then as a wardsman at Royal Brisbane Hospital.

Moffatt: “I mixed the tracks the next day and Ivor picked the tape up.

“He later called back asking me to turn the drums down saying ‘We’re not a drum band’.

“I still don’t know to this day what they played that first 15 IPS mix on, who made that decision, or even what happened to the tape.

“Anyway, I reworked the mix, pulling the drums back and that was the tape Ed took to Astor to have 500 copies pressed.

“It seemed to me Ed and Chris naturally drove the process, just with the nature of their performance, and Ivor was behind the idea of doing a recording so he looked after that part of it.”

“Like a snake calling on the phone”

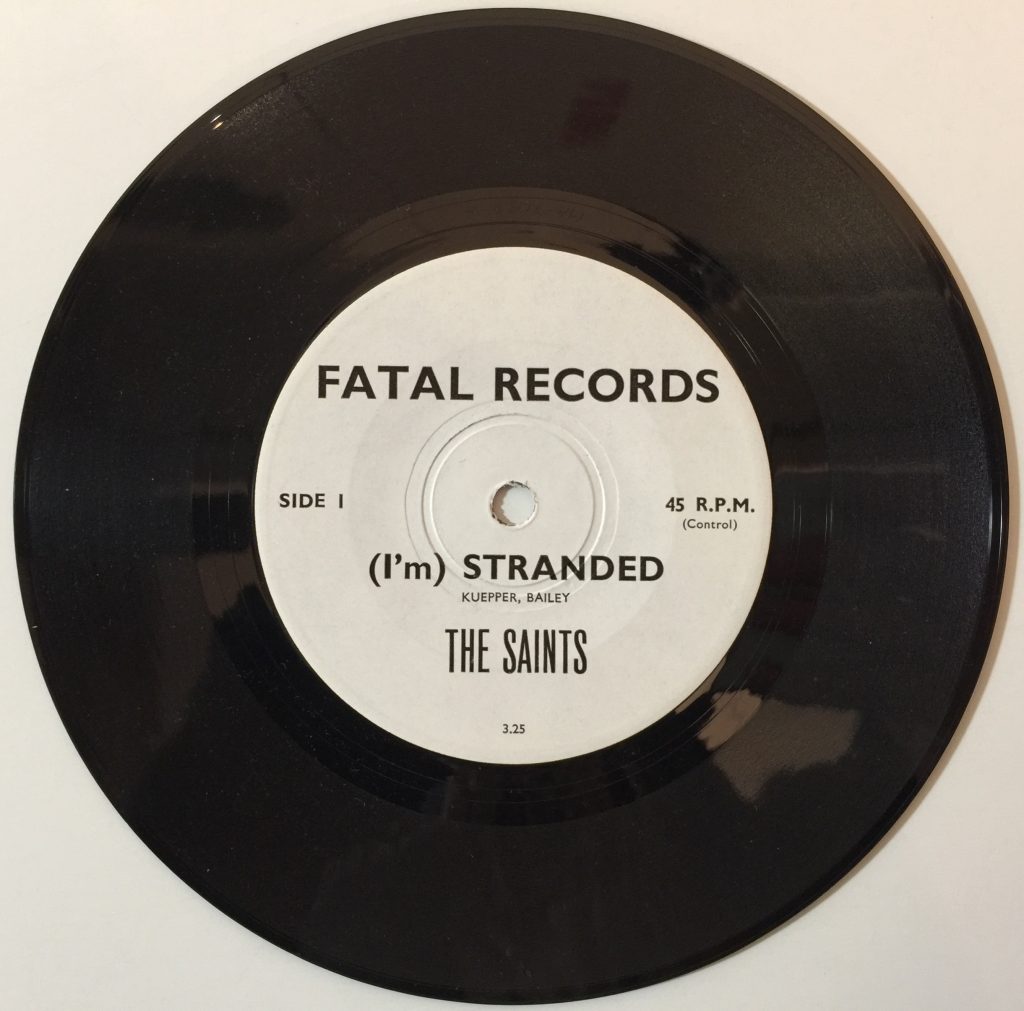

They put the single out through their own Fatal Records in September 1976. It cost $2, from their marketing and PR company Eternal Productions.

Copies were slow-mailed to all the record companies in Australia. No one called back. Even those who liked its guitar buzzsaw found Bailey’s ‘blank generation’ monotone irritating.

The Australian rock press was impressed but it was the UK media that turned it up over 10.

The UK release of ‘(I’m) Stranded’ (through tiny label Power Exchange) was four months after The Ramones’ first album but well before The Clash, The Damned, and The Sex Pistols.

The Saints became the ‘face of the new punk explosion’ and Bob Geldof would say, “Rock music in the ’70s was changed by three bands – The Sex Pistols, The Ramones, and The Saints.”

Moffatt, asked about the importance of the recording of ‘(I’m) Stranded’ to Brisbane, responds: “Don’t get me started!! Brisbane had always punched way above its weight.

“It started with Mick Hadley arriving in ’62 fresh from the London blues scene which led to the Purple Hearts and the unique ‘60s hard edged Brisbane blues scene.

“Brian Cadd once told me the Hearts actually physically frightened audiences when they moved to Melbourne!

“Sadly back then Brisbane was viewed as a backwater and the repressive politics of the day prevented the city getting any recognition for its considerable contribution to Australian music.

“I mean, the classic ‘Black and Blue’ Chain line up was in essence a Brisbane band and its success helped form the basis of the Gudinski empire.

“’(I’m) Stranded’ not only broke down all the Brisbane stigma in Australia but had an enormous effect globally, being credited as one of the songs that changed music in the ‘70s.”

The Saints achieved success on their own terms which had a huge impact on other musicians.

“They had that ‘fuck you’ attitude down like no other band that I’d seen,” observed Nick Cave.

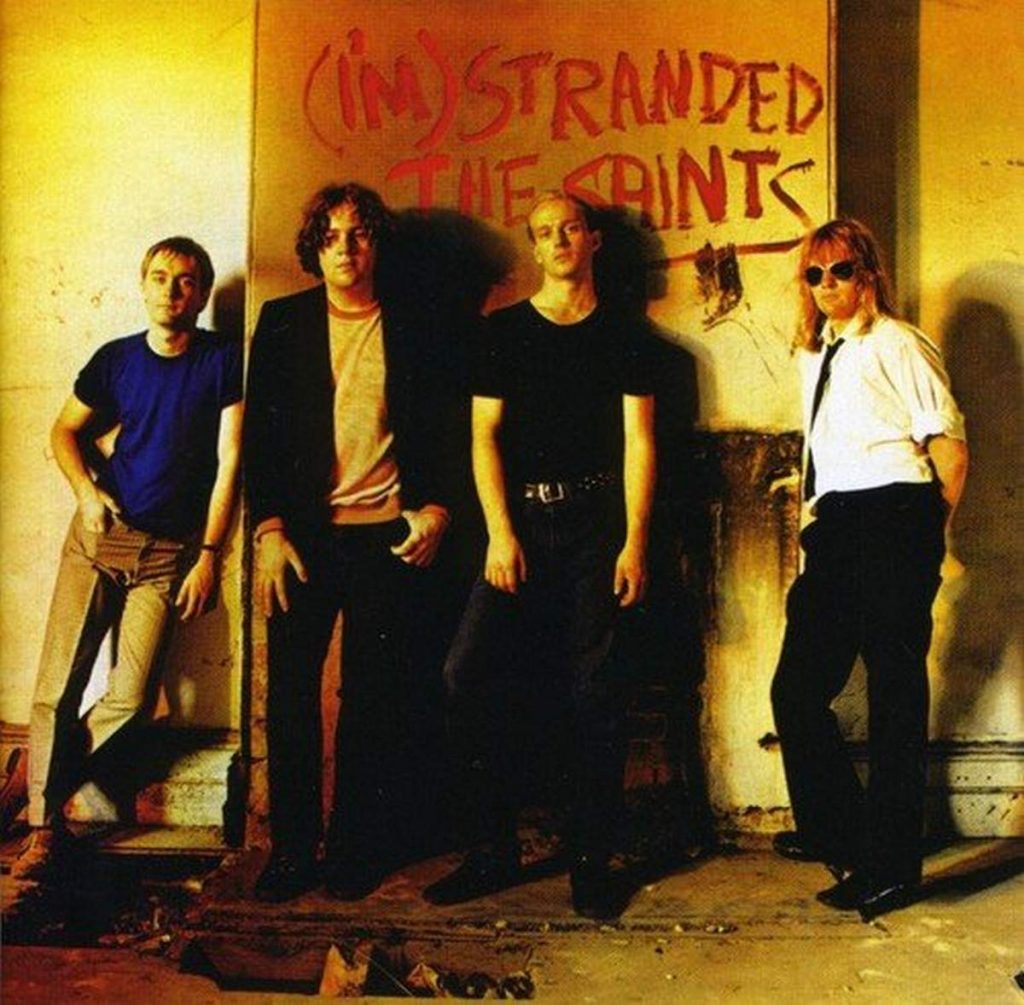

The accompanying video, directed by Russell Mulcahy, was filmed at a messy abandoned terrace house in Paddington.

The front cover of their debut album (February 1977) was shot here too, the four sullenly standing before a fireplace with “(I’m)” Stranded daubed in red paint. Fans would trek to be photographed before the fireplace, until the house got pulled down.

Gaping at the rave reviews, EMI UK sent a message to its Australian operations: sign them!

The Saints did shows in Sydney and Melbourne and, contrary to myth, appeared on Countdown.

Before long, the relationship between Kuepper and Bailey imploded, as did the lineup. Kuepper went on to create wide ranging styles of compelling music and his playing was cited as unique.

Bailey kept The Saints going but veered them towards a softer sound. He would refer to the early Saints as “a kiddies band”, which worsened the friction with Ed.

There were unsuccessful attempts to patch up – the duo and Hay reunited to perform one song for their ARIA Hall Of Fame induction in 2011 – but Kuepper is saddened that any further conciliatory moves obviously ended after Bailey died in April 2022 at his home in Holland.

“Part of keeping the legacy of the original Saints has been very very difficult because of the band’s split up and the determination by Chris to diminish the legacy of the original band.

“That was the cause of the hostility between us. Sadly it never resolved properly.

“We made a few attempts but it just shows you get things done when people are still around.”

In 2007, ‘(I’m) Stranded’ was added to the National Film and Sound Archive’s Sounds of Australia registry.

Mixdown: How much has the record sold?

Kuepper: “Ha, no fucking idea. We really got ripped off lots. The money that has been paid on it has been miniscule.

“There have been a number of releases that weren’t official.

Mixdown: “Were you ever asked to let ‘(I’m) Stranded’ be used in an ad or movie?

Kuepper: “Lots of movies.”

Although EMI was aware that Moffatt had done the single, he got no credit on the album until the box set, although the band had in interviews repeatedly acknowledged his involvement.

Moffatt became an awarded producer (Yothu Yindi, The Divinyl, Neil & Tim Finn) until he relocated to Nashville in 1996, where one of his major projects was the launch of Keith Urban.

Window Studio was sold to Leon Prescott who renamed it Sunshine and continued recording with The Go Betweens and Powderfinger.

In the late ‘70s, Prescott sold the console for $4,000 to Tasmanian audio engineer and producer Nick Armstrong, who carted in his station wagon to Hobart with his friend Peter Hutchison and installed it in Spectangle Productions recording studio.

When he sold the business, the console went to ABC engineers apparently used for training.

Recalls Moffatt, “Unaware of its history, they scavenged some parts and dumped the rest of the console so it’s now land fill!

“This all came to light after the ABC ran a story on my search for the console.”

Read more on the search here.