The second album for The Japanese House – the dream-pop project of singer, songwriter and producer Amber Bain – arrives just over four years after her acclaimed debut 'Good At Falling'.

It could well be argued one’s second album is prone to just as many cliches as their debut. You know the ones: The “difficult” second album, and how they say you have a lifetime to write your first and a few months for the next. That being said, this folklore is actually a big part of why it’s so surprising how effortless In the End It Always Does sounds. The second album for The Japanese House – the dream-pop project of singer, songwriter and producer Amber Bain – arrives just over four years after her acclaimed debut Good At Falling, and promptly exceeds that already-excellent LP with her strongest and most thoughtful material to date. So, how did Bain avoid the dreaded sophomore slump? Simple: By not treating it like a sophomore.

Read up on all the latest features and columns here.

“I think I’ve always been more of a song-by-song kind of girl,” she explains to Mixdown from her London home over Zoom.

“I don’t really tend to sit down and go, ‘right, I’m going to make a record, starting now’. I don’t find setting all these sorts of rules before you go into writing music to be particularly helpful – to me, not having them really allows for more creativity in a lot of ways. My taste is very eclectic; I don’t really listen to one genre of music. I also have a really short attention span. I think both of those things really factored into the songs for this album – I don’t think that ‘Friends’ and ‘One for sorrow, two for Joni Jones’ could have been on the same album if I’d been aiming for a singular sound.”

Indeed, the widescreen and ornately-arranged sound of In the End sees Bain extend her vision to the farthest reaches of The Japanese House’s sound yet. It’s simultaneously home to her loudest, her quietest, her poppiest and her weirdest songs yet – quite the impressive feat for an artist who’s never once rested on her laurels. She forged the album in collaboration with The 1975 drummer/producer George Daniel, whom Bain has worked with for over a decade, as well as enlisting the likes of MUNA, Matty Healy and Justin Vernon to contribute. There’s a lot more visitors to Bain’s proverbial House this time around than on Good At Falling, which she reveals was done entirely by design. “It was a very conscious decision,” she says.

“I’d been trying to prove a point with The Japanese House – I can produce this, I can do this and that, I can make everything myself – because people find it really hard to believe that a woman can do all of that. People would always be like, ‘Oh, that part’s obviously played by this guy’, and it was me who played it. It made me wary of collaborating with people, because I was concerned that would mean I was relinquishing credit.”

And now?

“Now I just don’t really care, because it’s just going to happen anyway,” Bain resolves. “I might as well collaborate with my friends who are great musicians. Who cares if I don’t get all the credit? I don’t need all the credit anymore.”

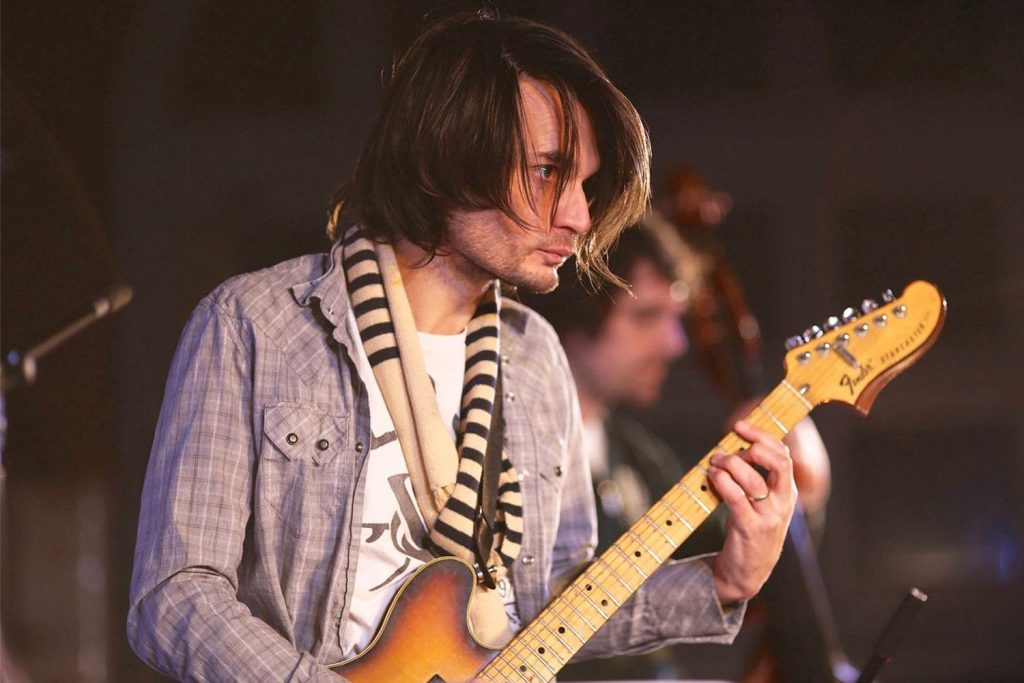

A myriad of various instrumentation serves as the building blocks of In the End. There’s the striking violin, which is played by Polly Mackey, which Bain sees as the emotive core of the album: “There’s just something about hearing that instrument played in front of you that can just move you to tears,” she sighs. There’s also the introicate guitar work, which Bain admits comes about in a lot less glorious manner: “I actually don’t give a shit about guitar models or pedals,” she laughs. “If it sounds nice, let’s do it. It’s less romantic, and more about speed.”

Central to the shimmering sonics of In the End, however, is Bain’s use of piano, which runs through the LP as either a foundational pillar or an extra layer of sparkle atop an otherwise electronically-driven composition. While many would simply opt for a keyboard – or even a weighted keyboard, if you wanted to get extra fancy – to achieve this sound, Bain sought out the real thing for the album. The way it feels on the album, she says, is a full credit to its engineer Chloe Kraemer. “She records things in this way that whatever you put in front of her, she’ll make it sound incredible. She goes about things in such a classic sense, and I think the whole thing sounds amazing.”

Bain notes that the only time a real piano wasn’t used on In the End was on ‘Spot Dog’, which was done on a Nord electric piano. “The only reason we didn’t replace it is because I completely forgot how the fuck I played it the first time,” she laughs. “I tried, but I just couldn’t figure it out! Everything else, even that twinkly sound at the start of ‘Sad to Breathe’… that was all done on real pianos. It’s not very heavily effected at all – especially on a song like ‘Joni Jones’, which is pretty raw as it is.” As if on cue, a loud bark rings out. Could that be the Joni Jones? “It is!” Bain beams. “She’s just coming to terms with her newfound fame.”

Bain then calls out off-mic to her beloved dog. “I’m very happy for you,” she yells, “but you need to get over yourself!”

Keep up to date with all things The Japanese House here.