Having just released his first-ever signature pedal with Fender, Kevin Shields sits down with Mixdown to chat about his relationship to shoegaze as a phenomenon, vacuum cleaner memes and how the collaboration first came to be.

There are few names, nor musical projects, as culturally synonymous with the word ‘shoegaze’ as Kevin Shields and his band My Bloody Valentine. If brought up in conversation, the descriptor tends to roll off of the alternative music fanatic’s tongue with the seamless ease of the lush, reverberant guitar chords that we in the 21st century have come to understand to be the hallmark of the genre.

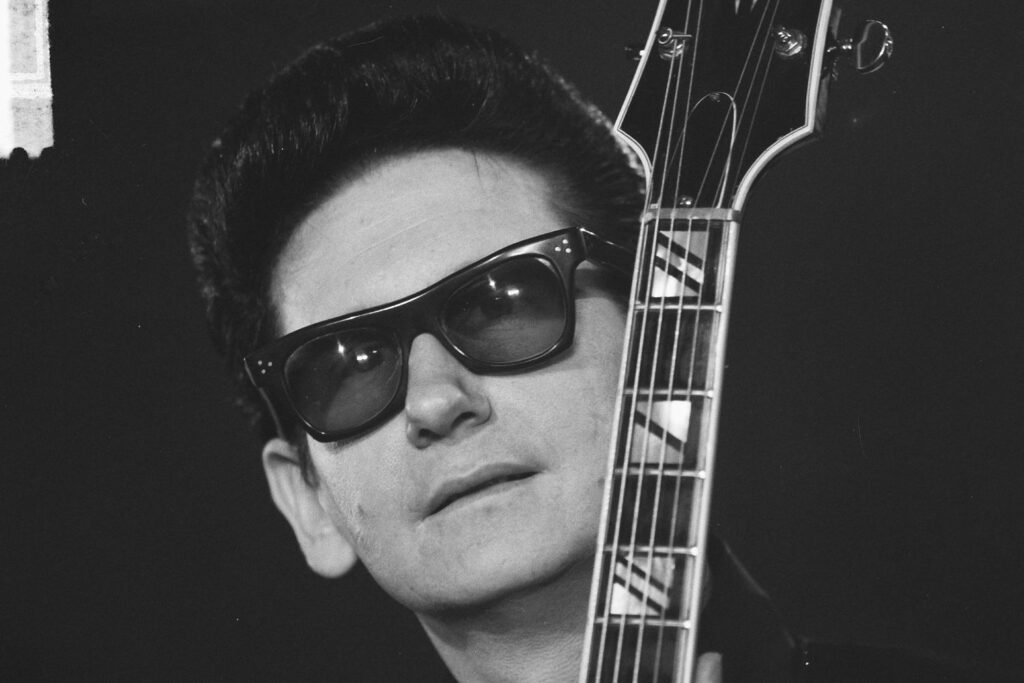

Kevin Shields

Having come into contact with Kevin’s music in the mid-2010s as a chronically online teen, digitally crate digging for rock music of yore on Youtube and Tumblr, I wasn’t just enchanted by MBV’s euphoric blare of distorted guitars, but the narrative that the band, and the other acts with which they have been algorithmically aligned, from Slowdive, to The Jesus and Mary Chain and The Cocteau Twins, came to me parcelled in.

Read up on all the latest features and columns here.

“It’s called shoegazing because they used so many guitar pedals that they were always staring down at their feet,” a shaggy indie lad I had a crush on at nineteen first informed me.

More googling led me to find that these pedals were largely of the reverb variety, and that loads of them, utilised to create infinite stacks of guitar overdubs, were precisely what unlocked the keys to the shoegaze kingdom. This research also shaped my perception of these bands as underdogs – renegade rebels; intensely praised, and then subsequently smited by the UK music press, only for their records to re-emerge as beloved, underground classics in subsequent decades.

However, when I’m granted the opportunity to interview Kevin Shields, and I begin by asking what his relationship to shoegaze as a phenomenon is – having been heralded, effectively, as one of its progenitors – this idyllic vision of hordes of mop-topped, stompbox worshipping, alt kids banding together to infiltrate pubs and clubs across the UK quickly becomes sand in my fingers. His response leads me to reflect on the contemporary music industry’s compulsion to neatly categorise; to posthumously narrativise music history so that it can be neatly curated for streaming platforms, listicles and other forms of digital media. I’m left wondering whether many of the bands I’ve described as ‘shoegaze’ in the past, should even be described that way at all.

My Bloody Valentine

“There’s been an internet retelling of things that leaves out all of the American bands, you know, like bands like Dinosaur Jr were very influential at the time… Sonic Youth as well, to the UK bands. And there were bands like House of Love for example, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of them, but they were on Creation Records, and they were quite influential to a lot of the bands like Ride and stuff that were called shoegazing…

“It’s difficult, because at the time those bands all did what they did, and they pretty much all jumped ship and became brit pop bands or 60s influenced – that’s the two directions bands went in. Or Americana, Mazzy Star influenced stuff like Slowdive, for example. So while all those bands went off and did what they did, we were just us as usual, and then, pretty much, bands around the world, you know, American bands and bands everywhere really, made that term shoegaze not seem like that really rotten, garbage term that it was at the time. [In the 90s] it was purely a put-down. We did a tour in 1991, and by the end of it, it was declared by the NME in a big headline – this band has killed shoegaze. We weren’t even considered part of shoegaze at the time. It’s something that really only happened in the 2000s, like in the past 20 years or so… but we weren’t really part of that at the time.”

One of the key reasons that Kevin somewhat rejects the collating of such diverse bands under the umbrella of such a prescriptive genre, is its flattening effect – the way it can distort and colour a listener’s experience of a project.

“The thing I don’t like about this whole thing of being called a shoegaze band, is because – I’m gonna give you an example – all people are very affected by words and concepts; preconceived ideas… There’s an old saying, if you’re gardening and you see a beautiful thing and you say oh, I see a rose, this beautiful rose, then immediately you’re seeing less than you would see if you just absorbed it. You’re imposing all of your conditioning and all of your ideas onto it. An example of that would be a song we have, “Only Shallow”, it’s the first song on Loveless and basically, people were making a documentary about pedals, and they said, ‘can we use this as an example of using reverb?’, and I was like, well, it doesn’t have any reverb on it. That song has zero reverb. And they were like, ‘really?!’ and it’s like, just because it doesn’t sound like something standard, that doesn’t mean I’m using an effects pedal – I always said I wasn’t. People then hear what you do in a haze of preconceived ideas, like oh, this is just some studio effects, or loads of effects pedals or loads of guitar overdubs, or whatever. It’s stealing from [people], the ability to hear things the way they are.

There was a little sub genre they were trying to create, the TikTok world… ‘Sad Music’, we were being included in that, and what’s interesting about that, is that a guy, for his PhD, in music school or whatever, did a thing on Loveless like 20 years ago, and one of the things he noticed was that there’s no minor chords in it. It’s not got one sad chord, ironically, it’s mostly major… I was like, is it? … That’s the irony of that world. People are so determined to make categories that they’re ignoring reality.”

I tell Kevin that I agree, and that in the same way that having the emotive complexity of his work reduced to ‘sad’ sounds frustrating, it must be equally so, to have his studio craft reduced to a genre marker touted to be easily sonically replicable – requiring not the patient mastery of guitar playing and studio engineering, but that you just ‘slap a load of effects on everything.’

“Luckily for us that didn’t happen for a good 15 years, you know, we did what we did, we weren’t so tarnished with that. From 1991 to about 2001 the general thing was “studio manipulation”, that’s what people used to say, “using the studio as an instrument”, those kinds of terms. People kind of got that it wasn’t all about effects – barely – but they couldn’t get over the fact that it wasn’t millions of overdubs. As it blended into we’re a shoegazing band or whatever, it just became like ‘oh, they use loads of effects’. You have completely respectable guitar magazines, writing whole articles about us using millions of effects pedals in the studio, and millions of overdubs, because their research is just the internet, and the internet… I would say is about, 80% always inaccurate.

So my opinion is just complicated. I don’t care very much, but I know it’s ultimately negative. But on the other hand it is its own thing. I remember when punk happened, I know it’s hard to believe now, but most of the punk bands were saying ‘we’re not a punk band’. I remember reading it as a kid and thinking oh, shut up. You are a punk band, and we love you for it. So I’m aware of that. I’m aware that it’s a bit boring hearing somebody going blah blah blah about shoegaze or whatever. You’ve gotta remember that everything we sound like was set in stone before the first so-called shoegazing band had even put a record out. We are that. If we sound like them, it’s because they sound like us. Not the other way around. We don’t have a shared influence… this kind of Cocteau Twins, Jesus and Mary Chain thing, it’s garbage. You know, Psycho Candy would be the shared record. But everything The Jesus and Mary Chain did back then we were not doing. And Cocteau Twins, we were kind of going against all of that – operatic vocals, loads of effects on the guitars – I love the Cocteau Twins but I didn’t want to sound like them.

We were very influenced by the American music scene, you know, that was very dry production, very visceral. Not reliant on loads of effects, not kind of wet sounding and kind of distant – d’you know what I mean? We were very much the opposite of that, even though we were doing stuff that was very strange sounding it wasn’t that… this echoey, cold stuff. Even though I loved most of it. I still do. But I didn’t want to do that because I had other influences, and other things I loved too. Lots of influences that have nothing to do with music.”

I tell Kevin that the band’s earlier work he’s referring to is some of my favourite, with its driven, percussive guitars; that I certainly see the band and Sonic Youth in the same milieu, and that I adore that music for its visceral dissonance.

“I don’t hear dissonance, you know, weird fact… I don’t know what people are talking about. I just don’t understand it. I just hear more, like if it’s the two notes, and they’re supposedly dissonant, I hear the third note that occurs. But it sounds beautiful. And together, it makes a beautiful triangle.

I don’t know why. But I mean, I hear a fan, it sounds musical to me. And that’s become a joke. When people say people use vacuum cleaners… Yeah, like, sounds good! Don’t you hear the melody in that?”

Though I’m delighted to find that Kevin is aware of the vacuum cleaner shoegaze meme-iverse and would love to know what other reddit-borne tom-foolery he has come across, I move on, intrigued to hear whether there were any particular moments, or discoveries in his early career that lead him from recording the dryer, noisier, rhythmic guitars on MBV’s earlier work, to creating the enormous, transportative soundscapes of Loveless.

“Basically, we started out as a band that was really into The Birthday Party and Einstürzende Neubauten. Quite physical… quite aggressive… but it wasn’t aggressive in a macho way… it’s that wildness… But I was also into the Beatles. And I was also into melodic things.

“There was a real extreme noise thing that was really happening when we were first starting out. And our early gigs are based around a Portastudio, that we would basically record. I had a Yamaha CS-5 synth, and that was as much my main instrument as a guitar was. And banging things and recording weird percussion things onto the Portastudio was also what we did, as much as drums – Colm would just go crazy in a kind of a Birthday Party jazz kind of way… Just being explosive, more than keeping up a rhythm. And our singer would just be screaming randomly over the whole thing, you know, so that’s how we started, and then we got into a kind of garage rock music… There was also an element of like – we kind of decided to leave Ireland and we really slimmed everything down. I just got a Jazzmaster copy guitar, a little tiny Casio keyboard, and we had a snare drum and sticks. And that was our whole [rig].

So we went to Europe… and there were a lot of crucial moments, there’s this thing called the Atonal Festival in Berlin… it was all these bands like Test Department… they’re just kind of extreme noise, kind of using all sorts of strange things, banging metal and stuff. And also in that period, I saw Einstürzende Neubauten do a gig called love songs. And they did a song called “Sand” by Lee Hazelwood and Nancy Sinatra. That, for me, was a huge click moment, because they were literally having Molotov Cocktails on stage, and it was just the sound of… war and chaos, but with this amazing song. Experiencing that, you know, the hugeness of it. It was so non-traditional. And yet with a really great traditional kind of song. Around that same time, Jesus Mary Chain brought out their first single. So those things were all kind of pulling towards that.”

Conscious that our time is almost up, I move to ask Kevin about his just-announced collaboration with Fender on his first ever signature pedal – The Fender Shields Blender. Knowing what I know now about how he feels about the perceived homogeneity of pedal-driven shoegaze, I’m a little coy when asking my pre-prepared questions regarding whether the unit is a tool that will in any way aid users in replicating the hallmarks of his sound.

“[Laughs] No, no. Basically, I mean, my connection to the Fender Blender was that I bought one years ago, and nobody was using them and then I got known for using one, in the 80s. Then in around 2018. I was over in America touring, and I was at the Fender offices, and one of the guys that works with people like us, Jason, said, are there any pedals, or any sounds that you don’t have that you would like? Basically, are there any ideas you’ve got that haven’t been done? And I said yes. And then a year or two later, they just were like, oh, yeah, so we’re thinking of re-issuing the Fender Blender, but we were talking about some ideas that you have – would you be interested in incorporating them? And I was like, yes, definitely, you know, that’d be really cool. Basically me and a guy called Stan, the designer, used the Fender Blender as the template and then added things.”

These seem to be the ideal collaborative conditions for an artist like Kevin, who, in spite of the internet’s tendency to miss-historicise he and his bandmates as the ancestral figureheads of an interconnected web of reverberant guitar bands droning and weaving into one another, has always worked entirely instinctually, from a creative impulse that is deeply personal and renders him peerless in his craft.

“When it’s something you use, that’s in your domain and something you’ve really liked, that you’re particularly fond of, and then you get to be involved with, it’s always just, it’s just kind of just fun, it’s not stressful, it’s just like, a nice thing to do.”

Find more information about the Fender Shields Blender at Fender Music Australia.