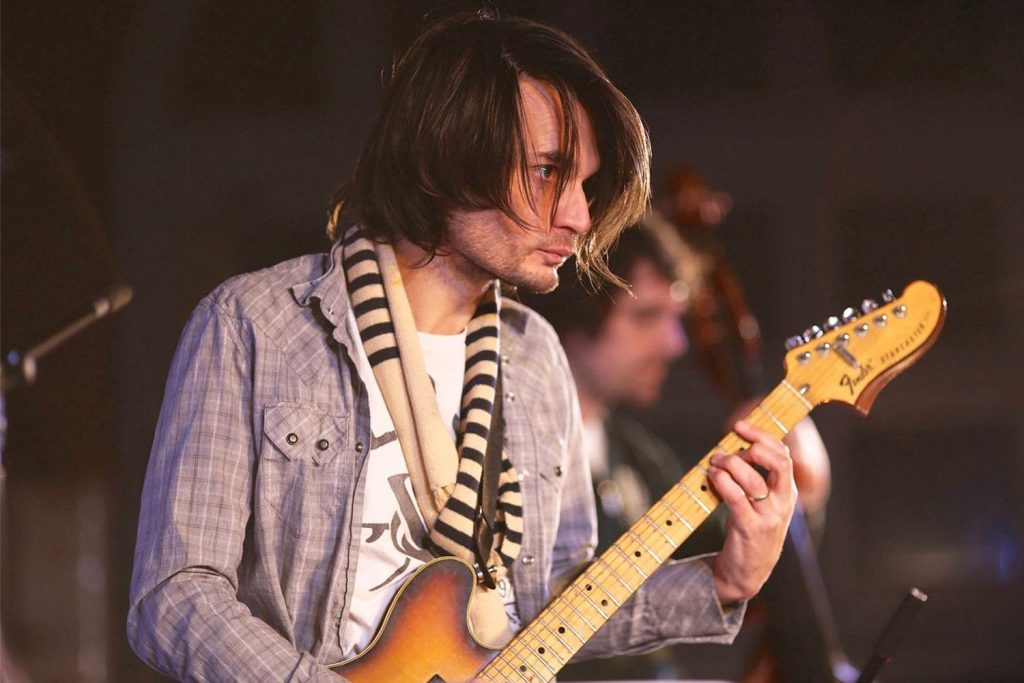

Photos by Zoe Wiseman

Charlie Clouser sat down with us to chat about the journey that led him to composing for film and TV, his producing workflow, and the career-high significance that the release of Saw X represents.

Former Nine Inch Nails member Charlie Clouser’s work has thrillingly scored our collective nightmares for decades, with the producer, remix artist and composer set to break the US record for most consecutive films scored for a franchise with the forthcoming release of Saw X.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

The ticking industrial beats, bone rattling drones and shrieking strings of the iconic Saw theme “Hello Zepp” have become a cultural touchpoint for contemporary horror scores the world over; a Frankenstein-ed re-appropriation of the sonic hallmarks of classic spook-cinema that carved out a new way to amplify terror on screen. Ahead of this monumentous new release, and reuniting on stage with Nine Inch Nails last year for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Charlie sat down with us to chat about the journey that led him to composing for film and TV, his ideal production workflow, and his impending career-high marked by the release of Saw X.

I’m under the impression that composition for film and television is a career that one doesn’t always necessarily find themselves in by design – with a storied career as an alternative musician, remix artist, producer and more under your belt, I wonder if this is true in your case? How did you first break into the field?

I did kind of slide sideways into scoring, but it wasn’t by accident. One of the first situations where I was being paid to make music was working for a record producer who had transitioned to composing scores for television in the late eighties. I was only 23 or so, and although I was uncredited, and I wasn’t actually writing any cues, I did all of the synth and drum programming and created all of the sounds we used in the scores, so early on I had a great introduction into the world of scoring for an hour-long weekly network tv series. Working as the right-hand man to an established composer was a great way to see how the sausage got made and learn the workflow, the terminology, and what worked and didn’t, musically speaking. After a couple years of that I moved from NYC to LA to continue working with that composer, and that’s when I got more into remixing, album production and programming, and eventually into the Nine Inch Nails camp. That was a fun couple of decades, but when I left NIN in 2001 and returned to LA and knew I wanted to continue down the scoring path. I was always more interested in unusual musical sound design than straight-ahead rock songs, so NIN was the best possible situation for that within the context of making records, but scoring is even more of a free-form musical landscape and it was inevitable that I’d gravitate towards that. Around that time, I reunited with the composer I’d worked with so many years before, and together we scored another network series, but this time I had my name on the credits, and that unlocked the door to taking on serious scoring projects on my own. So even though I was a refugee from a band, I already had years of experience under my belt, and I wasn’t coming into it totally cold.

Before you began working as a composer, what was your relationship to film/audiovisual media like? Have you always perceived a synesthetic connection between image and sound? What kind of films do you personally gravitate towards?

Even from childhood I had been interested in film music, but not so much the mainstream, melodic, heroic-theme type of stuff like Indiana Jones or whatever. I was always more drawn to the music from films like Hitchcock thrillers and horror films like The Shining and sci-fi like Planet Of The Apes. Even though they were mostly orchestral, those films always seemed to have more of an experimental musical sound design feel, and that’s what I found interesting. I still remember seeing The Shining as a teenager and thinking that the music sounded exactly like what a person who is slowly going insane must be hearing inside their head, and the Ligeti choral music in 2001:A Space Odyssey conjured up the sound of the unknown. So I’ve always paid attention to film music, I love it when it works, and I’ve tried to hone my skills in that direction. Even though many of my favorite films and scores tend to be action movies and espionage thrillers, my natural musical and sound design tendencies seem to be more appropriate for psychological thrillers and horror movies, so it’s no surprise that those are the genres where I’ve wound up having the most success.

With such a wide array of projects under your belt, I’d love to know where do you typically glean inspiration from at the beginning of a project? Could you briefly walk us through your creative/production process from the commissioning of a score to its delivery?

For me, it’s all about the sounds. That’s where the first inspiration usually comes from, and an interesting sound always suggests a mood or musical direction to me. I’ve always been a huge collector and curator of interesting sounds and samples, and I’m obsessed with organizing and categorizing my collection so that I can find what I want quickly. At the start of any scoring project, I first build a new template in Logic that contains a collection of sampler instances with most of the sounds I think I’ll want to use, and it’s a different collection for each project. These days my template has nearly 1,000 instrument tracks, with sounds drawn from over 100,000 candidates, and each one has compression, eq, reverbs and delays already in place, so each sound is pretty much ready to go, with everything routed and levels already set to give me a good starting point. Once that template is put together, I then do what I call “wire frame” mockups of each piece of music in the entire film, and these are usually just so I can nail down some very basic aspects like key and tempo, and for these I’ll just use simple, basic sounds so that I can move quickly and get the major musical motifs sketched out, often just piano, harp, strings, and some basic percussion. But at this stage I do spend quite a bit of time getting the tempo and time signature maps really nailed down. I like to get very precise about having musical phrases be very tightly in sync to picture, so that it’s exactly eight bars from the door slam to the gun shot or whatever, and I spend a lot of time just listening to click tracks against picture at this point while I build those tempo maps. I’ll lay in some very basic percussion, piano, and strings parts just to make sure things feel right against picture, and then I move on to the next cue until I’ve at least touched on every scene in the whole film. I like to make the analogy to a child’s colouring book; at this stage I’m creating the line-drawings that form the outlines of each drawing, so that later I only need to concentrate on deciding whether the clown’s nose should be orange or green. After this stage is complete, then the fun begins….

Once I’ve got some kind of rough outline for each cue, I can begin recording new raw audio that will be specific to that project. That involves recording oddball acoustic instruments like my collection of bowed metal devices, a disassembled piano, a ghuzheng, weird guitar gadgetry like E-Bow, Sustainer, and Gizmotron through a ton of pedals, maybe some circuit-bent cheap synths and my modular synths, etc. Since I’m recording into my sketches, I already have some sense of the tempo, key, and mood I need to work with, so it’s not like I’m just recording audio against empty click tracks. I jump around from cue to cue, recording until I run out of gas and then moving to another, and sometimes I’ll hit upon a sound and think, “Ooooh this would work great on that scene towards the end”, and since I already have a sketch template for every scene, I can quickly load up that cue and record into it before I lose the moment.

Once I feel like I have enough raw material recorded, the process of editing and processing begins. Some of the stuff I record will wind up being turned into banks of samples that I can trigger from the keyboard, so I process, edit, and build sample maps for that stuff right then and there. Other recordings will be used in-place and as-is, and still others will remain as long audio files, but I’ll manipulate their tempo and pitch in Ableton Live and place them in whichever cue I think they’re needed.

This all might take anywhere from a week to a month, so by this point I really need to get serious and start writing some actual music. I continue to jump around between the cues, so that I bring them all up to the same level of completeness as I go. Sort of like what you’d do when making records, where you’d have a white board with a grid, and check off the boxes for each song as you completed the drums, the drum edits, the rhythm guitars, the guide vocal, etc. That way I don’t have any nasty surprises, and when the director wants to hear where I’m at I can play the whole film with sketches, then half-finished versions, and finally the almost-finished versions.

Could you talk a little bit about your typical workflow/ recording set up? Does this vary a great deal from project to project?

I use Logic on Mac as my main composition and mixing environment, and I also use Ableton Live as an alternative DAW for manipulating pitch and time and messing with its various time-stretching and granular modes to destroy my raw audio recordings. Within Logic, each audio or instrument track is routed to one of fifteen stem sub-masters, and those stems are summed inside Logic to create the composite mix. Each stem is either stereo, quad, 5.1, or 7.1 depending on the project, and has its own reverb and delay effects in the appropriate surround format. Those stems each appear as separate outputs on my audio interfaces, and also get summed inside Logic to a composite mix.

I use a second Mac running Pro Tools as a stem recorder to capture all of the stems and the composite mix in a single pass. This lets me output my stuff without bouncing inside Logic, and I can capture all of the stems and the mix at once. Another thing I love about using a separate stem recorder is that it gives me an overview of the whole reel or project, so I can hear the end of one cue playing back from ProTools while the beginning of the next cue is playing live from Logic, which makes it much easier to finesse those overlaps. These days I use MADI to get between the Logic and ProTools rigs, so I have 64 channels going across, which lately I’ve configured as fifteen stems plus the composite mix, each in quad. If I need to deliver in 5.1 or 7.1 then obviously I must use fewer stems, but if I’m in stereo then I can use more. I may move to a Dante-based setup to raise the number of channels to 128 or 256 going between the rigs.

I also use a third Mac running VideoSync software so that the picture is being played back from a separate machine, slaved to MTC from Logic, which is a great workflow for me. This eliminates the need to have the movie files inside my Logic projects, and gives me some flexibility to compare earlier vs later revisions of the picture, etc.

When I scored the first SAW film, I gave a lot of thought to setting up my template, the stem routings, and all that stuff so that my setup would be flexible and fast, and although the hardware has changed over the last twenty years, the basic workflow is the same as it was in 2003. Back then I still used three Macs, but I only had twenty-four channels of ADAT going between Logic and ProTools. So now I have more channels but the basic concept is identical.

The sonic landscape you have built over the course of the SAW films is so integral to their potency. From “Hello Zepp” and beyond, these scores have a powerful point of difference; a refined aesthetic and strong POV that has made them a continual reference point for modern horror music. How did you initially conceive of SAW’s aural world, and how has it developed over the course of the franchise? Do you find that you have certain compositional tendencies that you fall back on to translate that mounting sense of tension and release the movies are synonymous with?

I consider myself extremely lucky to have worked on such a long-running and popular franchise as the SAW films, but of course at the start we had no idea it would still be going strong ten films and twenty years later! But there were some “master plan” ideas in the first movie that have been consistent across all of the films. In the first film, the plan was for the music to start gently, grow more dark and heavy as themes were established, and then descend and dissolve until by the third act it was basically noise and chaos, just banging and scraping metal, until the final cue when we wanted it to feel like the lights had been switched on, just a huge tonal shift. So that final cue, called “Hello Zepp”, is in a different key and uses different instruments than any other music in the score. Most of the SAW films follow a similar road map, where the intensity and chaos builds until a big shift near the end.

In terms of the musical sound design, I’m always trying to make the sounds that I’m using feel as if they’re native to the setting of each scene. So, if we’re in some dark, dank, underground dungeon the sounds will be cavernous and dark… plenty of bowed metals and no woodwinds! To me, things like big, epic taiko drums usually sound like an army on horseback should be coming over the hill, so those typically don’t feel right to me for a SAW movie. I always want it to feel like the score is taking place in the same space that we’re seeing on the screen. If the setting is claustrophobic, then I want the music to sound claustrophobic as well. This gives me some guidance in terms of what sounds and effects I use, and helps me keep the sound focused.

Are there any consistent motifs that you deem indispensable to the narrative world of the franchise?

There are quite a few musical phrases, chord progressions, and melodies that are associated with certain characters or even settings in the films, and these re-appear throughout the franchise when appropriate. Even if I’m doing a spacey, sound-design-y cue that might barely be classified as music, I’ll use those chords and melodies as the raw material even if the sounds are atonal or ambient textures. This helps give a little bit of cohesion across the whole of a score. It might not be apparent on the surface, but I’d like to think it helps.

The musical motifs also have some arcs that span entire films, and one thing I like to do is to create a sort of graph or timeline that represents the moods and intensity over time. This is sort of like the coloring-book analogy I mentioned before. One “trick” I often use is to have all the modulation of key and root notes moving downwards for the whole film, as if the score is helping to drag the victims down to their doom. Then, if I suddenly start moving upwards in key it makes a strong impact. I often start by mapping out the root note movement before I’ve even started figuring out the chords and melodies, and this helps me build a road map that I can follow as I build the score. Again, more of that coloring-book technique.

One thing that I find really inspiring about your work for film and TV is the fact that many of the compositions you have created, like “Hello Zepp”, have enjoyed fanfare and a life of their own separate to the project they were conceived for. Take the American Horror Story theme for example – I can’t tell you how many people I’ve encountered who have shared the sentiment that it impacted them equally, if not more, than the narrative and visual contents of the show. What do you think it is that makes your work stand out?

I’m grateful to hear that, and I can’t help but think that my background in working on song-based stuff with bands contributes to that somewhat. I’ve always loved a good, memorable hook or riff, but that sort of thing is only appropriate in a few spots in a film score. But when it’s the right thing to do, I don’t hold back. With the “Hello Zepp” theme, and with some other themes like those in another James Wan movie that I scored, Dead Silence, James was totally on-board with the idea that the score should be bold and memorable in those spots. But one thing I always keep in mind is that there’s often a lot of information coming at the audience in those scenes, which are often at the climax or big reveal moment in the films. So even though I want a big, bold theme, it can’t demand too much of the audience’s attention or else it might get distracting. That’s why those themes need to be sort of like a tasty guitar riff that can be understood quickly, almost bite-sized musical events. Once those simple riffs are established, I can build and layer upon them without pulling the audience’s attention away from the story.

To wrap things up, I’d love to know what part of your creative process brings you the most joy? When do you most feel the magic? And what exciting projects do you have on the horizon?

My favorite part of the whole process is when I’m about halfway into it, once I’ve got those wire-frame outlines of the cues established, and I’m having fun experimenting with sounds and themes. At that point I’m no longer terrified of the blank pages stretching out to infinity, but I haven’t yet gotten bogged down in the tedium of dragging the thing across the finish line. Around that halfway point, there’s still the possibility that I won’t totally ruin everything in the process of finishing it.

Keep up to date with Charlie Clouser and all things Saw X score here.