"The Dan", to some, were just a band.

But Steely Dan, quite simply, weren’t a duo who harboured any predetermined interest in commercial success, with much of their subsequent output oftentimes too thorny for the mainstream palate. From 1972-77, the band released six studio albums, each demonstrating a growing propensity towards sophisticated jazz progressions, cryptic lyrics, as well as a mellifluous approach towards studio production.

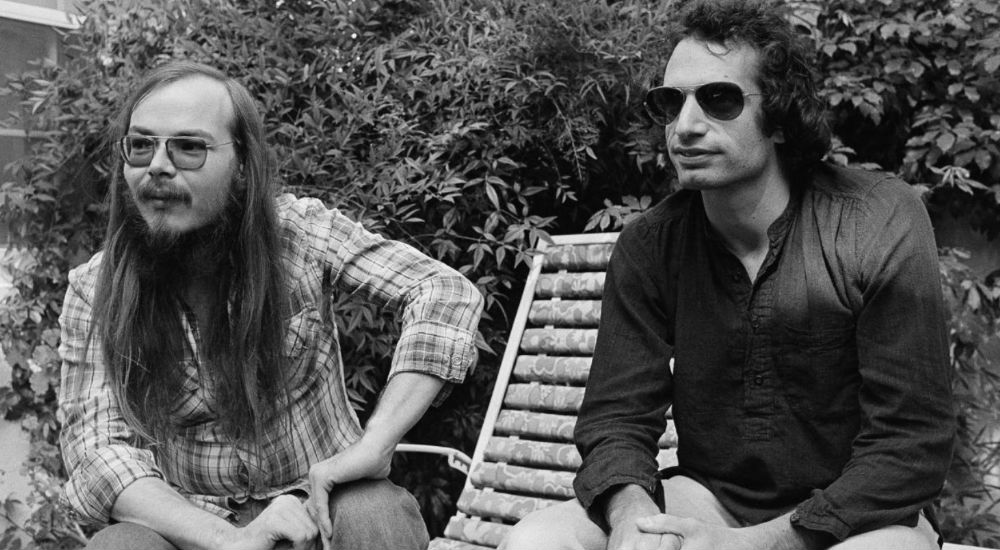

Steely Dan

The Leather Canary

Fagen and Becker met at Bard College, a number of years prior to the foundation of the Dan. Wind the clock back to a Halloween party in 1967, inside a gloomy old common room at the College. Most of the shindiggers are tripping on acid while a trio named The Leather Canary, situated on a small stage in the corner, rip through some Rolling Stones and Willie Dixon covers. Fagen provides keys and vocals, Becker guitar, while a fellow student by the name of Chevy Chase sits behind the kit. Chase, who went on to become one of the most revered comedians of his generation, would eventually describe The Leather Canary as “a bad jazz band”. While Chase decided to pursue a career in comedy, Fagen and Becker stubbornly stuck with the jazz aesthetic – a gutsy move amidst the zeitgeist of psychedelia popularised by bands such as The Doors, Jefferson Airplane and The Byrds.

Read up on all the latest features and columns here.

After trying their hand as record ghostwriters, the pair realised their songwriting was too left-field for the pop sensibilities of Barbra Streisand, and subsequently chose to relocate to Los Angeles. It was on the West Coast in 1972 that the pair formed Steely Dan – at that point consisting of Fagen and Becker, alongside guitarists Denny Dias and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, drummer Jim Hodder and additional vocalist David Palmer.

Steely Dan songs

Upon signing to ABC records, they released their debut album Can’t Buy A Thrill: a sensationally written LP featuring a unique amalgamation of Latin jazz, roots, and soul inflections throughout. Their follow-up album, Countdown To Ecstasy, enjoyed critical success, but did not fare as well commercially. After the release of perhaps their most experimental record, Pretzel Logic, bandleaders Becker and Fagen took a leaf out of The Beatles’ textbook; they decided to stop touring and instead devote all of their time to writing and recording. This decision led to the departures of the other band members, effectively rendering Steely Dan a studio project.

Pretzel Logic

Always privy to a virtually unlimited studio budget, the two began recruiting some of the finest session musicians to perform on their records. Pretzel Logic featured future Toto keyboardist David Paich, as well as bassist Chuck Rainey, whose funky P-Bass lines are heard on many of Aretha Franklin’s hits. Becker recalled “once I met Chuck Rainey, I felt there really was no need for me to be bringing my bass to the studio anymore.” The duo soon began to view themselves more as songwriters and producers, who sometimes opted for more technically competent musicians to record their music.

I would personally characterise much of Steely Dan’s music as a wild orgy of dark lyrical narratives, sonic sheen, and harmonic perplexity. Their songs often contain disturbing fictional scenarios with shady characters, with songs such as ‘Charlie Freak’ exemplifying this. Here, a heroin addict decides to sell his dealer his last remaining possession – a gold ring – in order to get his next fix. The dealer eventually finds ‘Charlie’ dead from overdose, and out of guilt, restores the “ring [he] could not own” to his dead hand. I dare say this would’ve made even the Velvet Underground feel a bit queasy.

Becker and Fagen were also sheer perfectionists, and sometimes demanded in excess of 40 takes from session artists. It’s a well-known fact that the Dan pissed a lot of musos off, and were sometimes rather unpleasant to work with. Dire Straits frontman Mark Knopfler once compared the experience of working with the duo to “getting into a swimming pool with lead weights tied to your boots”. But for Steely Dan, this was all done in the name of perfecting the art of studio recording.

Aja

Fagen and Becker both shared a deep passion for jazz, with its influence deeply imbued within their last few records. 1977’s Aja – arguably their magnum opus – features jazz legends such as saxophonist Wayne Shorter, guitarist Larry Carlton and drummer Steve Gadd. The combination of Shorter and Gadd on the title track is nothing short of electric; an effort only those two icons of the genre could have supplied.

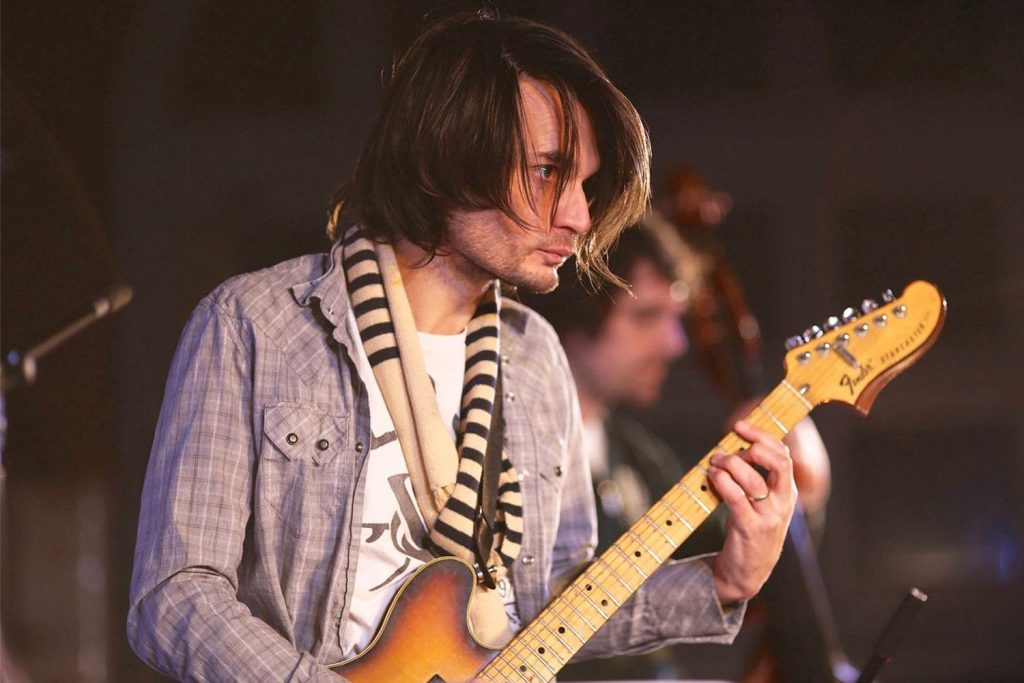

Steely Dan’s application of jazz harmony within a rock-songwriting blueprint was unrivalled in its intricacy and audacity. Their innovative use of the μ (Mu) chord became their signature; Becker described how it seeks to enrich the sound of your major chord “without turning it into a jazz chord”. The Mu chord is basically like your typical sus2 chord, but with the major third always paired next to it. For example, the chorus in ‘Reelin’ In The Years’ relies on a back and forth between G μ (5th fret on guitar) and A μ:

Their use of voice leading was Bill Evans-esque; one of many examples being the lead up to the chorus in ‘Hey Nineteen’:

The linearity between these chordal configurations was well-suited for the brass sections deployed by the duo, especially throughout their last few albums.

Steely Dan’s genius lay within their ability to envelop some of the most conceivably fucked up lyrical themes inside of a sleek, meticulously-produced finished product. The A-Grade session musicians employed by perfectionists Becker and Fagen provided the veneer for their observations of society’s grotesque imperfections. It is the ironical wit, songwriting mastery and toil for perfection that’ll ensure Steely Dan’s output stands the test of time.

Keep up with Steely Dan more recently here.