Investigating the latest financial trend to hit the music industry.

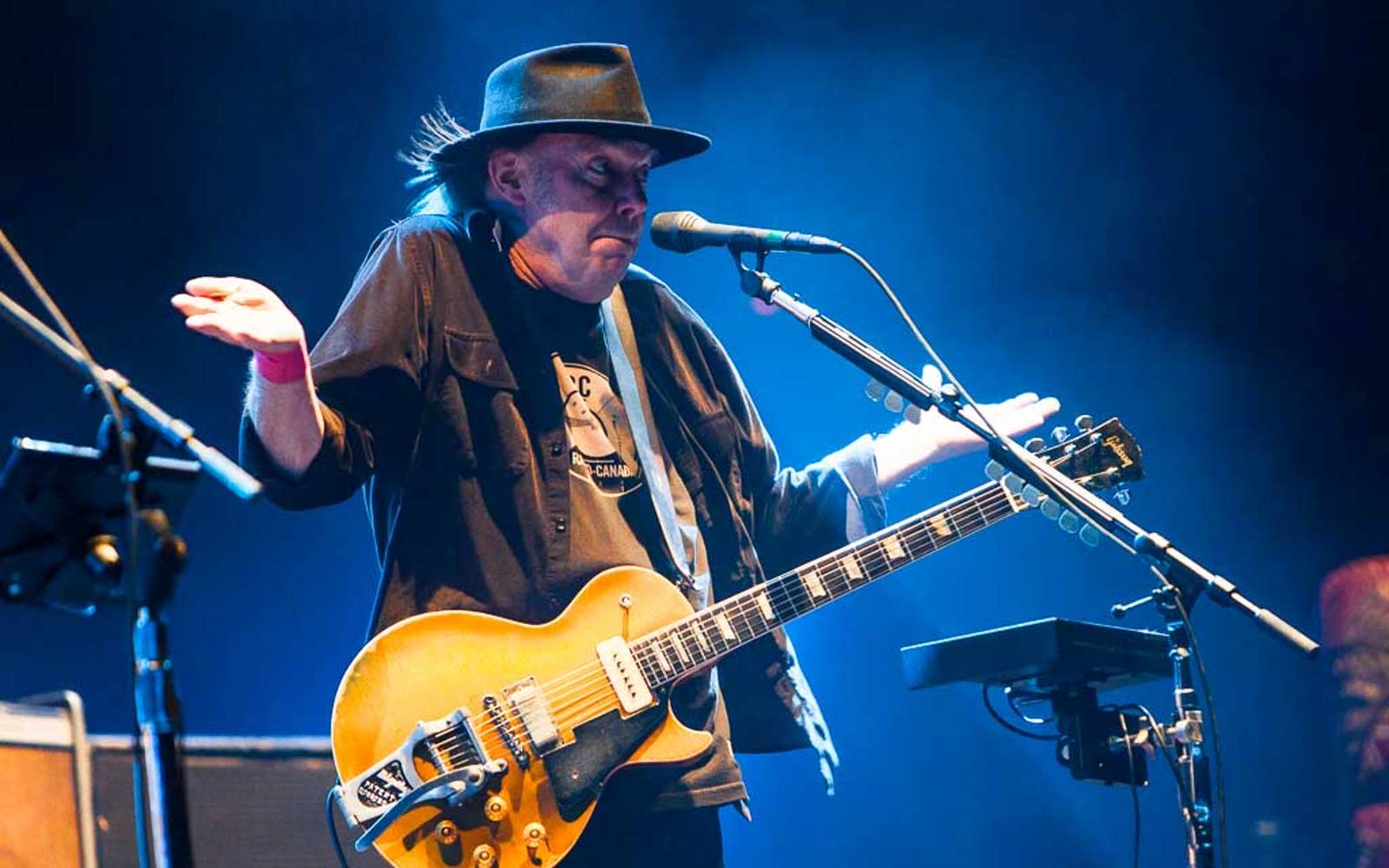

Over the past few months, there’s been an influx of headlines about ageing rockers banking in on their music publishing rights for big money. A few years ago, Neil Young – previously a hardened opponent to his music being licensed for commercials – sold off 50% of his publishing rights to Hipgnosis Song Fund for a reported $150m, while former Fleetwood Mac guitarist Lindsey Buckingham and Interscope Records mogul Jimmy Iovine have made headlines by selling their respective publishing and production catalogues to the song fund.

Stevie Nicks

Buckingham’s Fleetwood Mac bandmate Stevie Nicks also raked in the cash by selling her publishing rights to Primary Wave for $80m in 2020 as “Dreams” experienced an unprecedented TikTok resurgence, while other prominent names to have dabbled in the publishing game range from Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA, super producer Mark Ronson, pop hitmaker Jack Antonoff and Debbie Harry of Blondie.

It’s no secret that it’s tough to make a buck in music nowadays. Every other week, we’re reminded of the brutal industry monopoly held by major streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music, and with touring as we once knew it quickly becoming a fading memory thanks to the pandemic, there’s no doubting it’s a bleak work environment today for artists trying to make a buck.

Neil Young

So, why should artists like Neil Young and Bob Dylan – veterans of the music industry and cultural icons who are unlikely to ever worry over a penny – sell off their publishing rights? Are they simply shooing away their classics in order to beef up their estates in preparation to kick the bucket, or is there something else at play?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it seems that most major publishing catalogue acquisitions today do tend to revolve around money. Even long after their time on the charts has expired, songs can continue to roll over a profit through three established channels: mechanical royalties (physical sales or paid downloads), performance royalties (music being played live, on TV, in a bar or via streaming) or through synchs (songs being licensed for advertising, movies or other multimedia).

While all three streams are a viable way of raking in the cash, it’s the latter that tends to be the biggest cash cow for musicians. As physical sales (for the most part) continue to dwindle and the prospect of touring remains stagnant – even more so for ageing artists – a lump sum payment with as many zeroes as Bob Dylan’s publishing agreement can seem incredibly alluring. Sadly, for some older artists – David Crosby included – it seems like the only way to make a dollar today.

On the flip side, if you’re an investor lining up for a slice of publishing pie, you’re also setting yourself up for a pretty healthy pay cheque every time a track gets played, purchased or synched – and when you’ve got as many gems in your catalogue as someone like Bob Dylan or Neil Young, you’re essentially guaranteed to make bank.

In a story filed by Mark Sweeney for The Guardian, MIDiA Research analyst Mark Mulligan staked the claim that ‘the music publishing deal market is at its peak’, stating that many publishing deals are currently being done for up to 15 times their value, with the potential to be even greater for big names with big hits. There’s no telling whether or not these figures for such deals will skyrocket or slide in the foreseeable future, which is just one reason why so many major artists are cashing out while it’s hot.

However, it’s not just the notion of a lump sum payment for these publishing deals that makes them so enticing (although it definitely doesn’t hurt). As Forbes have previously noted, these major deals also hold significant tax benefits for artists when compared to conventional recurring royalty payments.

In the United States, ongoing royalty cheques are considered to be regular income, whereas a lump sum payment can be treated as long-term capital gains. This means more cash to splash today, and less woes when the feds come knocking around tax time – a no brainer for any self-respecting rock star, really.

Another key factor in a number of these decisions comes down to who the artist is dealing with, and what agreement they’ve struck with whoever has purchased their publishing catalogue. Contrary to popular belief, firms like Hipgnosis and and Primary Wave are substantially invested in the commercial and intellectual interests of artists, which is why so many veterans are putting pen to paper with them.

Hipgnosis, for instance, is led by music mogul Merck Mercuridas, a passionate music executive with a history managing acts like Iron Maiden, Elton John and Guns N’ Roses, and likes to make a habit of referring to his business model as ‘song management’ as opposed to publishing. He’s even appointed Chic legend Nile Rodgers to the firm’s advisory board to help make a bold statement to any potential client: under his care, hit songs won’t ever stop being hit songs, and subsequently, will only ever hold or grow in value.

It’s also worth noting that for the most part, publishing catalogue deals are far less dodgy than they seem. The majority of conventional publishing catalogue deals still allow artists to retain an input over how their own works are used, and it’s the artist who gets to have the final say in the decision. Unless there’s an agreement that involves the total acquisition of an artist’s masters – as exemplified last year when Hipgnosis purchased the masters of the Kaiser Chiefs – there’s a good chance your music isn’t going to turn up in lewd commercials or sub-par action flicks if you do strike a deal.

Kaiser Chiefs

Perhaps one of the most unspoken benefits for partaking in a publishing rights deal is that of upholding an artist’s legacy. As grim as it may be to think about now, many of our favourite artists from the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s are well into their twilight years, and for them, it must seem far more enticing to have a say in how their music is handled post-mortem while they’re still alive – after all, we’ve all seen how the drama with the Prince estate has played out.

Artists don’t want their musical legacy to be marred by bitter family disputes over royalties and publishing when they’ve passed away; they just want their songs to be listened to and loved as they have while they were alive. Plus, the idea of a healthy lump sum payment with long-term capital gains certainly doesn’t go astray either, does it?

Keep reading about Hipgnosis Songs here.