One of the biggest enigmas that eludes new mix engineers lies in the topic of compression. Mixers of all skills and experience levels use it daily and love it, yet I constantly see threads online filled with compression enquiries ascertaining this notion.

Parallel compression is also known as ‘New York Compression’ is a way to harness the best of both worlds: the crunch and squash of a heavily compressed signal, while retaining the dynamic and punch of the performance. Let’s start with a quote:

‘It takes time to train the ear to hear compression, and the multitude of ways it can be implemented are nearly endless’

And at the base of it all, this is entirely understandable. It takes time to train the ear to hear compression, and the multitude of ways it can be implemented are nearly endless. In addition to this, haven’t even touched on the different characteristics and functions of various compressor types “whether hardware or digital”.

However, my intention with this article isn’t to construct a Compression 101, resources are abundant for this information online ready for any reader who needs to brush up on the topic.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

Instead, I would like to emphasise the topic of parallel compression, a technique that has gained much prominence in both mixing and mastering circles and become quite fashionable in recent times.

Audio Compression “In Layman Terms”

At its most basic interpretation, compression can be viewed as a form of dynamic control. Most commonly a compressor will reduce the dynamic range of whatever source audio is run through it so that the loudest parts are brought below a pre-determined threshold. This type of compression is commonly referred to as “Downward Compression”.

However, there also exists “Uplift Compression”. Uplift Compression will essentially increase the volume of the quietest sections in your source audio whilst maintaining the same peak level at the compressor’s output stage “provided you are using the same compressor settings”. This works by increasing the makeup gain control on the compressor itself.

Truly Uplifting

A side effect of normal downward compression is that such processing will change the characteristics of loud signals. This is just part of the inherent nature of downward compression but may be undesirable in some instances.

This brings to mind another solution, which would entail the attenuation of quieter signals without affecting the upper transients of the source. This in effect could be considered true “upwards” compression, but the truth to the matter is that it is extremely rare to find devices that will accommodate such a task “at least in the hardware world”.

However, hold back those astonished guffaws as even if hardware of this type was commonplace we would be hard-pressed to find much practical use for it as the amplification of the signals noise floor would be utterly appalling!

Side By Side

This is where parallel compression comes into play, by utilising typical ol’ downward compression we can achieve the same “upwards compression” effect we previously discussed without tarnishing our audio in the process.

I’ll take this opportunity to explain how parallel compression works, the concept is to split (or duplicate, or send) a signal into two paths. One path will be a through path that will pass without any processing, the other path will hit a downward compressor of the desired type.

After this, the compressor’s output signal will get summed with the unprocessed audio and then blended at unity gain. When setting up parallel compression you’ll find the best results using far more gain reduction than you would normally apply with a compressor.

In a parallel compression scenario, gain reduction of up to 40dB would be a great target this is far more gain reduction than what would be acceptable in a more typical compression application. This is why it is common to hear engineers refer to this technique as “slamming” or “crushing” the relevant bus, aux etc.

The result of this technique is that the peaks of the compressed signal are smashed down to a point where they are virtually insignificant when blended in as they will be dominated by the unprocessed through signal.

This means that our compressed signal now contains our quiet “but now louder” segments with all those precious transients safe and intact on the unprocessed signal.

On the other side of our coin, the transients at our peak levels are retained without compromise as they pass through freely within the through signal.

Obviously, the quietest segments of the audio won’t hit the compressor’s threshold and will remain uncompressed. However, it is worth mentioning that if two identical signals are mixed their output will be raised by summing together (approx. 3dB depending how you blend your two tracks!) This means that the quieter parts of the source audio will be raised in volume regardless, thus reinforcing the “upwards compression” effect.

In The Mix “Real World Applications”.

From vocals to entire mixes, the use of parallel compression within the scope of music production is practically limitless, engineers can utilise parallel compression in a plethora of ways.

Here are two common examples that you can try out yourself!

Drums

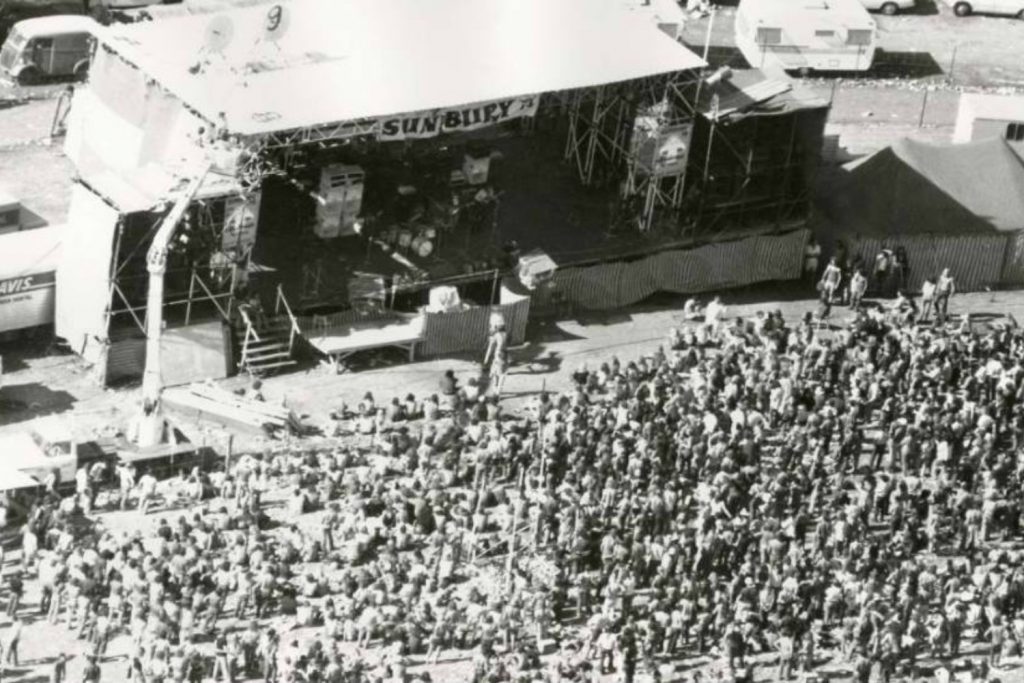

The use of parallel compression on the drum bus spans back many decades. A famous example of which that most will be able to quickly bring to mind is Led Zeppelins “When The Levee Breaks” from 1971’s Led Zeppelin IV.

When applied to a drum group, proper use of parallel compression will bring depth to your drum mixes. Providing a larger-than-life sound that is well suited for a variety of rock productions amongst other genres.

Bass

Implementing parallel compression on bass tracks can provide engineers with the opportunity to zone in on what parts of the frequency range they wish to compress. Providing extra control with how their bass sits in the mix whilst still retaining punch and girth.

For example, one may opt to utilise parallel compression to only compress the lower frequencies of a bass guitar. This is similar to how one may utilise a filter to let specific frequencies pass through void of any unnecessary processing.

Keep reading about New York compression with our friends at Baby Audio.