A refreshed lineup, coupled with recordings from beautiful studios with a stellar producer and an album is born.

20 years as a band is no mean feat, yet here are The Horrors celebrating the milestone with their sixth studio album Night Life, out today. Following a handful of singles including “More Than Life”, the album is a stoic, moody and gothy journey through The Horrors’ vast list of influences. It shifts seamlessly through industrial, post punk and electronic, melding analogue grit and digital rigidity into one incredible, contemporary sound. We caught up with frontman Faris Badwan about the recording making process.

Faris, thanks for taking the time and congrats on Night Life. How has The Horrors’ songwriting process changed over the twenty years you’ve been a band?

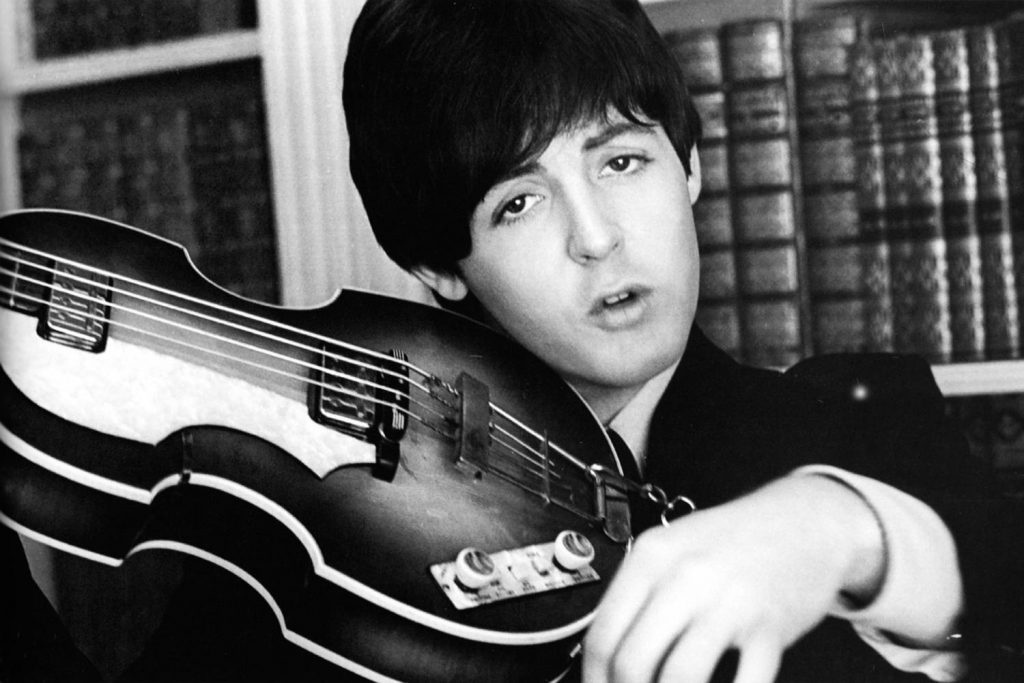

The Horrors began doing everything together as a group of five, and we learned to write songs through playing as much as anything else. We recorded our debut album (Strange House, 2007) in between intense runs of touring, and our second album (Primary Colours, 2009) was the first chance we’d had to actually spend an extended period of time experimenting and going deeper into sound design.

For Skying, we built our own studio, which we also used for Luminous. Around this time we began writing in different groups within the band, trying out writing in twos and threes as the process of doing everything as five people had started to become too inefficient. V continued in this manner, and then COVID happened, leading us to work remotely for most of the 2021 EPs.

So we’ve tried various methods, a lot of them kind of guided by the situations we found ourselves in. For Night Life, Rhys and I wrote the bulk of it together in his house, with very little outside input until we took it to the studio and began the process of building the final production and incorporating new members.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

Is there a clear delineation between end of songwriting and the start of recording?

I think it’s often a fairly blurred line just as a result of the way we work. Looking back at our past records, we feel like the best ones and the ones that feel the most natural all have a strong DIY element running through them. We’ve often incorporated sounds and parts from the original demos into the final recordings, as often spontaneous and instinctive stuff seems to have a character that we really like. We’re happy to leave in little incidental sounds, background noise, small mistakes – to us it just keeps a human element that gives those records life.

On one of the songs on Skying – “Wild Eyed” – we used a demo vocal recorded at my house and you can hear my phone ringing in the background of one of the verses. Night Life definitely keeps a lot of the DIY feeling, while being more refined in other places.

“I think that it takes a while to learn the value of space, and that taking elements away can often make certain parts have more impact.”

Can you speak a bit to the recording process for “More Than Life”?

It really varies. I began the song with a friend of mine, Jess Winter, in a room in Canary Wharf, but it only really started to sound like The Horrors once Rhys and I had worked on it together, which is often the case. We originally put the drums down in LA with a guy called Victor Indrizzo, who has a background in the industrial scene, but he was almost too good, and too precise. So on returning to London we redid the drums with a friend of ours, Jordan Cook, who has now joined the band full-time. He has a slightly different feeling that maybe is more natural to us, a bit more punk but still with great tone and character. We felt as if “More Than Life” could quite easily slip into being more ‘rock’ than we wanted, and it suited us to keep it a bit more understated.

Where did you record Night Life?

We recorded most of the demos at Rhys’ flat in North London, which is sort of Horrors HQ. There were a couple of exceptions— “More than Life” being one as I said, and “When the Rhythm Breaks” being another – demoed at Brendan Lynch’s studio in Willesden. The songs were mainly put down in Ableton, using synths and programmed drums and some guitar. As has often been the case, we used a few analogue synths for the writing process – a Korg Ms10 and Ms20, a Roland Juno 106, a Korg minilogue, a Roland SH-09.

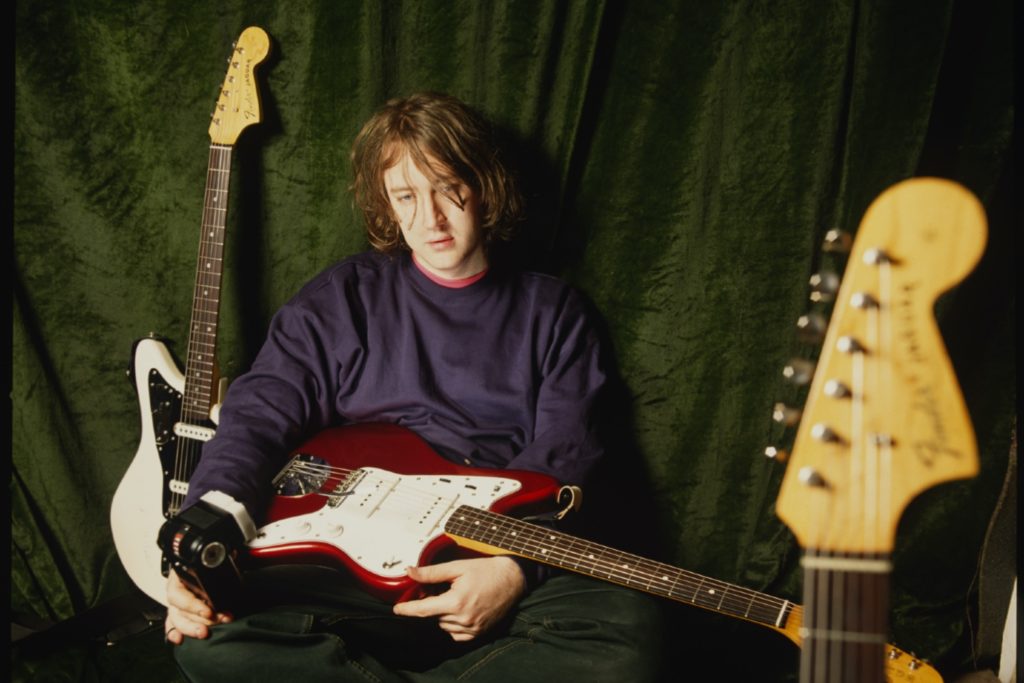

We began studio recording with Yves Rothman in London, at Holy Mountain Studios in Hackney. It was mainly Rhys (Webb, bass), me and Josh (Hayward, guitar and piano) at this point. Joe (Spurgeon, drums until 2024) came in for about two weeks at the beginning but realised that he wasn’t going to be able to commit to the entire process and took a step back.

Pretty much all the drums were programmed initially, and the focus was mostly on electronic sounds. Josh added guitar and I’m not even going to try and explain his setup because a lot of it is custom built, courtesy of his physics background.

Rhys and I flew to LA to work at Yves’ studio, the Bungalow at Sunset Sound, where we stayed for six weeks. We focussed on building solid arrangements for each track, with the view to refining more subtle details later. Yves had access to a lot of our favourite synths – like the Roland SH-09 which has appeared on most of our albums. We also began to add real drums and other live elements. We’ll often set up different work stations around the studio and move between them – I’d be refining lyrics and vocal parts while Rhys was looking at the sound design with Yves. Amelia (Kidd, keys) had appeared at this point, contributing additional production from her studio in Glasgow.

We then came back to the UK, and with very little remaining budget Rhys, Amelia, Yves and I set up a DIY recording space at an Air BnB in Tottenham, bringing all our gear in one last push to finish the recording. It was a slightly weird environment as the house belonged to a Christian Scientist with an extremely esoteric book collection. On the final day the entire row of kitchen cupboards detached itself from the wall, falling to the floor and completely destroying the place. There was no music playing and there’s no real explanation for why this happened. I was a few inches from being crushed.

We mixed the record with Craig Silvey, who has worked with us across our career. We tried to keep the rhythm parts fairly loose and avoided having everything locked to the grid, which meant redoing some of the drums. It was kind of the final piece of the puzzle really.

What is something you do during the writing/recording process now that you wish you’d known earlier in your career?

I think that it takes a while to learn the value of space, and that taking elements away can often make certain parts have more impact. I think on this record we’ve been way better at finding the right place for the vocal to sit, and I’m more often singing in my natural range now. It’s one of the things that seems to give the album as a whole a more personal, emotionally connected feeling.

For “When the Rhythm Breaks”, my Dad had recently had a heart attack and was in a coma. I did the demo vocal improvised, and couldn’t get anywhere near the same feeling when I tried to recreate it. So we just kept the demo – prioritising the feeling over a perfect technical take.

Now that the album is finished, you’ll have to perform it live. Does knowing you’ll have to perform it affect the recording process (extra layers, production, tracks etc.)? Or do you just make the record and figure it out?

We concentrate on making the record first. We definitely have it in the back of our minds that we’re going to want to perform live, but that doesn’t really influence the final result. With our current setup we have a lot of ways of adapting. We’re about to perform a series of record in-stores, presenting three-piece arrangements of an entire set, and I’m not sure it would have been as easy to do this in the past. We have a little more flexibility now and feel like this will put us in a good position for new material going forward.

Night Life is out now, listen everywhere here. You can keep up with The Horrors here.