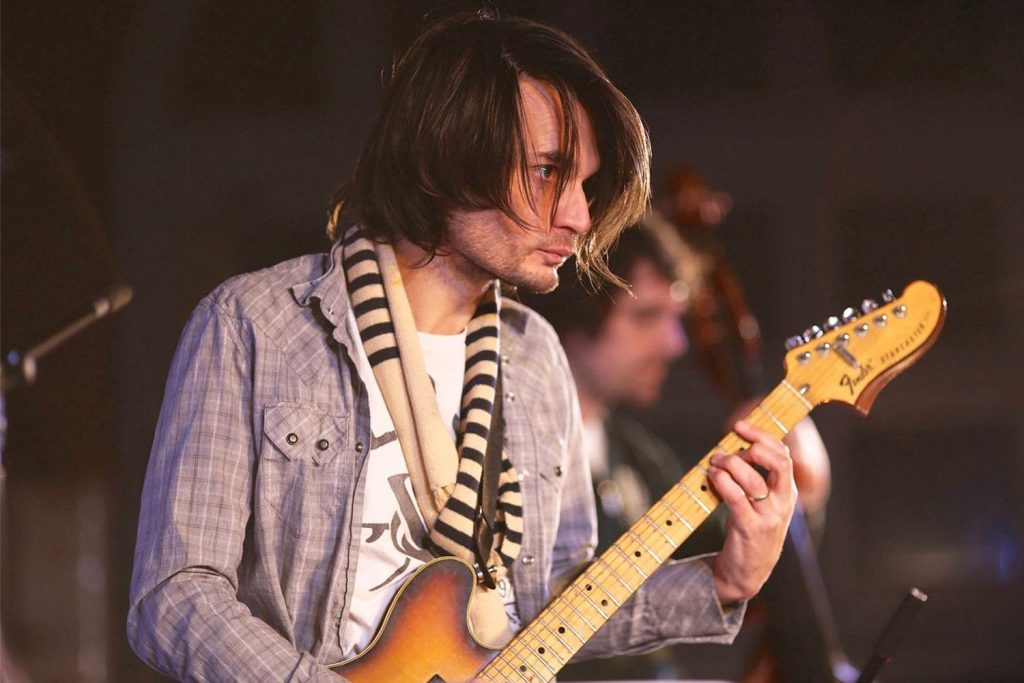

Holy Holy's Oscar Dawson is a producer and songwriter extraordinaire, with a workflow focused on getting sounds right at the source - as cliché as that might sound.

Holy Holy are a staple of Australian Music. Having formed in 2011, this year sees the release of the band’s fifth album, Cellophane. Ahead of the release, we spoke to Holy Holy member and producer Oscar Dawson about his work with the band, as well as being a producer for some of Australian music’s heavyweights.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

Oscar, thanks for taking the time! How do you define what you do?

Primarily I see myself as a musician. Being in a room with people making music is a comfortable environment for me. It’s where I began my journey in music, and so it’s where I feel the most fluent. From there I moved into songwriting, and as a byproduct, demo-making. These are the three entry-points to production for me – as opposed to, say, engineering.

I produce from the perspective of a musician, who likes to write songs with people, and spent a lot of time making demos. In fact, every co-write I work on these days involves some amount of production – it’s just the way songwriting tends to be. To this end, my approach to production revolves more around the dynamics of the instruments, the chords in the songs, the way sections flow, and structure, the arrangement, the tempo – rather than approaching production from the perspective of equipment, channels, compression, and so on. I’ve never felt comfortable referring to myself as an engineer, and don’t really see myself as one.

How does Cellophane fit into Holy Holy’s catalogue?

It’s our fifth record. We have been self-producing our music since our third record, My Own Pool Of Light, and have gradually become more and more ‘in-the-box’. This record features more programming, more loops and samples, and is more beat-driven than our previous ones.

It also features a lot of collaborations, which took place in all sorts of places, all around the country – and even overseas. As a result we had to be flexible with our recording arrangements – it couldn’t always take place in a pristine environment, we were often utilising the gear that was at hand, but ultimately the record-making process was liberating and easy-going as a result.

How does writing and producing songs for Holy Holy begin?

Writing and production go hand-in-hand these days. More often than not, we’ll have a kernel of an idea that’ll help us build a song. It might be a short voice memo from Tim [Carroll, the other half of Holy Holy] – him singing at home, or playing a motif on the piano. It might also be a short lyrical concept. Or, it might be a tempo. So we’ll take one of these ideas, and just make a start. We like to move quickly at the beginning – get some chords down, define the tempo, loop a sample.

From there quite quickly it is necessary to get Tim on headphones with a mic – any mic, whatever is on hand – and reverb. And have him start singing straight away. From there, we’ll just work on the song for one hour, maybe a bit more, until it starts feeling a bit sticky. Then, we stop, close it, and start another. If Tim has a voice memo, I’ll often bring it in to ProTools, see if I can find the key, maybe define (stretch, edit) it into a tempo, add some sounds, maybe some chords, some basic programming, to see if it has life. The key is to move quickly at this point.

Later – sometimes a month, sometimes longer – we’ll re-open these sessions, and if they make us feel good, we dig deeper. It’s a process that works best in bursts – short periods of activity and gaps.

How has working on music for other people ultimately affected your own work with Holy Holy?

It’s really hard to say. I guess I can only say that constantly working with other people introduces new ideas, new concepts, new references and new sounds in to my process. It helps to stop me from becoming insular. I love writing songs with people, in part, because I can get an insight into another mind and connect with ideas that are outside of my norm. Likewise with production.

A quick look over your Instagram shows a big console at the heart of your studio. What is it and how is it integrated into your workflow?

My goal with this Yamaha PM2000 was, and is, two-fold. One is to have more preamps. The other is to provide a platform for summing and flavour. The sad truth is that the console is currently down. The power supply is all burnt up. It’ll be back up soon, I hope. I have someone working on a new power supply. With old gear (this thing is over 40 years old), these things happen.

How do you usually record? Do you like to commit to sound?

It’s really both, there is no unipolar approach here. Instead of preamp, compression or EQ, I focus more on the sound-in-the-room. I know that is a cliche – but, when I receive files for mixing from other artists or producers, this is often (not always) the thing that requires the most attention. It’s not that the artist/producer didn’t consider preamp, compression or EQ, but rather, that they mightn’t have considered the actual source enough. I honestly think preamp, compression and EQ are overthought as key elements of the recording process and tend to only be a serious issue in misuse e.g. a preamp that distorts in an unpleasant way, or an over compressed vocal, or a bass with a low cut. That said, when I receive files for mixing, and I can tell the producer has spent a lot of time fashioning sounds in a really clever and artful way, has captured a great source with the right blend of compression and/or EQ, and the rough mix sounds beautiful, I’m so happy. It is a wonderful, glorious thing. Wow.

Is this true for your own music as well as music for others?

I’ve found as the years go by that I actually want things to have less compression and EQ overall. Sometimes I believe studios can become more like museums for grown-up’s toys and knick knacks, rather than a place to make music. So I try to focus on capturing good sounds and performances, rarely changing my approach from project to project, rather than fetishising equipment and spending long time worrying about gear choices. This applies to all projects. The truth is that the individual being recorded is more important. Ryan who plays drums for Holy Holy self-compresses in an incredible way, for example. I can’t think of a way that major compression can help his drums to sound better other than some bus compression and parallel compression. Some bass players I know, likewise, self-compress really well. I try to self-compress when I play guitar and bass. But, if someone doesn’t do this, I try my best to see it as a component of their style rather than an issue to repair; that is to say, I try to see it in a positive light. Sometimes it’s cool if someone plays in a janky way.

Thanks for your time! As a closing question, do you have any anecdotes you can share about the making of Cellophane?

A really great moment was the creation of “Messed Up”. This was an idea that Tim and I had worked on some time ago – back in the pre-Covid era. We had this synth motif and a tempo and Tim had some vocal ideas but we just felt like we couldn’t get the song over the line. Much later, I found that I just couldn’t let go of the song, so I reopened it and kept digging – but still, to no avail. Then we did a session with Tasman Keith, artist from NSW. We were working on a different song altogether – “This Time”. We were at the end of the session and struggling with a bass line, and he said – ‘why don’t I call my friend Kwame?’ Kwame is a great artists from Sydney. We said – ‘Great, sure.’

Tasman called him, and to our surprise, Kwame arrived in 20 minutes. He immediately fixed our bassline, and we thought – ‘Well, this guy is great.’ We asked him – ‘do you want to work on any more songs?’

As we departed the session, we sent him a Dropbox folder full of half-finished songs, of which “Messed Up” was one. Just the instrumental, none of Tim’s vocals. We thought nothing of it and assumed that, at best, we might touch base again a month or two later. The next morning, I’m at the airport, flying back home, and through comes a text from Kwame. He has attached a version of his version of “Messed Up” – with his own new verse, a chorus, re-edited, recorded, sounding great. It blew my mind. I felt so elated. He hadn’t even heard Tim’s vocals and lyrics, and yet, his verse fit perfectly. Amazing. Thanks Kwame!

Keep up with Holy Holy here.