We speak with EHX founder about building an effects empire, surviving bankruptcy, creating the Big Muff with a little help from Jimi Hendrix, and why he's still fighting through tariffs, wars, and an industry that never stops changing.

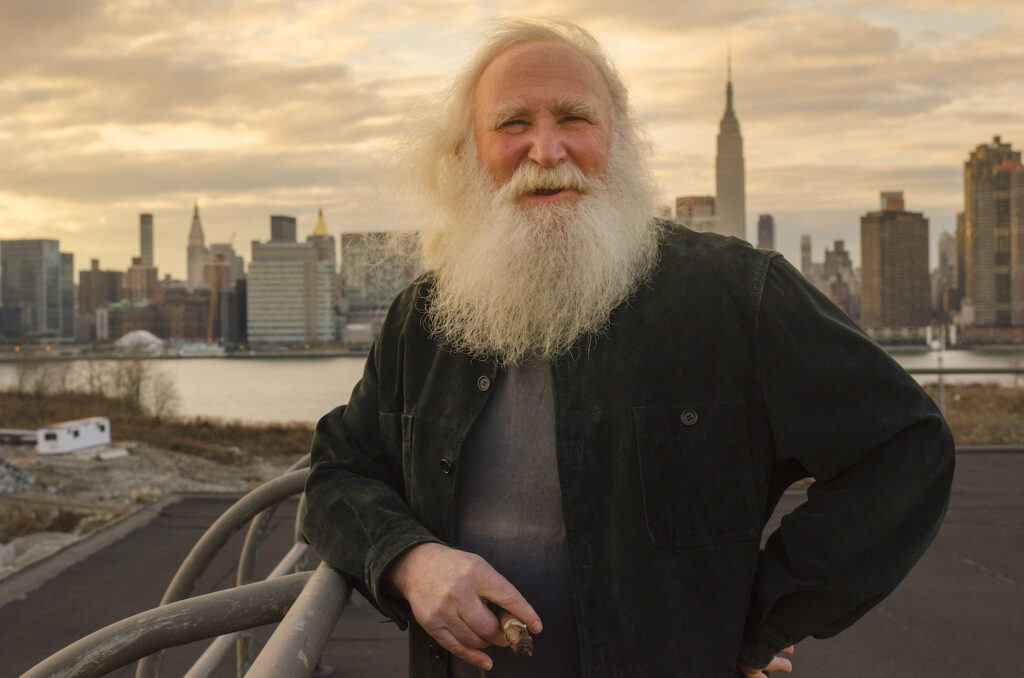

Certain names in the guitar world feel less like brands and more like geological features. They’ve always been there, they’ve shaped the landscape, and you don’t really question their existence; you just build your musical life around them. Electro-Harmonix is one of those names. And at the centre of it all is founder Mike Matthews: stubborn, funny, relentlessly practical, and still very much in the fight.

When I speak to Matthews, now 84, he sounds exactly like you’d hope. Sharp, direct, occasionally blunt, and still animated by the same thing that’s driven him since the late ’60s: getting sounds into musicians’ hands. He’s not sentimental about it. He’s not precious. And he’s definitely not done.

Catch up on all the latest features and interviews here.

“I’ve been doing this since 1968,” Matthews tells me, casually dropping a number that would represent several lifetimes in most industries. “I was very aggressive in the beginning. I was in a hurry.”

That hurry built Electro-Harmonix into one of the defining effects companies of the 1970s—and then, in the early ’80s, nearly destroyed it. Electro-Harmonix famously went bankrupt in the early ’80s, a moment Matthews speaks about with a kind of clear-eyed pragmatism. There’s no self-pity there, just lessons learned.

“I moved on everything,” he says of that first incarnation. “And eventually I went bankrupt.”

When he restarted the company in the late ’80s, it was with a very different mindset and an unexpected product focus. Instead of pedals, Matthews initially rebuilt Electro-Harmonix around vacuum tubes manufactured in Russia. It was a smart move at the time, and for years, tubes represented a huge portion of the company’s business.

But history has a way of looping back on itself. Matthews noticed that the pedals he’d sold in the ’70s (and sold in huge numbers) were now commanding serious money on the vintage market.

“It wasn’t like I sold a few,” he says. “I sold a lot of pedals in the ’70s. So this new vintage market developed.”

At first, he began manufacturing pedals in Russia. Eventually, production moved back to the US, where Electro-Harmonix pedals are now built once again. Today, pedals account for roughly 65 percent of the company’s business, with tubes, heavily impacted by the war in Ukraine and shifting tariffs, making up a much smaller share than they once did.

“We’re constantly battling through all these things,” Matthews says. “Tariffs, wars, constantly changing conditions. You’ve just got to fight through it.”

Matthews is refreshingly candid about where the musical instrument world sits in the broader economic picture. “Trump’s done a lot of good things for business,” he says, before immediately adding, “but that’s big business. The musical instrument business is not a big business.”

It’s a sentiment that rings true from every angle: manufacturers, retailers, and players alike. Prices rise, freight gets harder, and everyone has to adapt. Matthews doesn’t romanticise this reality. He treats it like weather: something you acknowledge, plan around, and keep moving through. That adaptability is part of why Electro-Harmonix has lasted as long as it has. The company has never tried to be everything to everyone. Instead, it has focused on making pedals that are powerful but approachable.

“Some companies are trending towards these huge multi-effects units,” Matthews says. “We like to make simpler pedals. Most people like them.”

As a player and someone who works in a guitar shop, I see this daily. Pedalboards are intensely personal things now—mosaics of analogue stompboxes, digital weirdness, old favourites and new experiments. Electro-Harmonix pedals don’t dictate how you should play. They invite you to combine, experiment, and personalise. Of course, with success comes imitation. Matthews is well aware that Electro-Harmonix designs, particularly the Big Muff, have been copied endlessly across the US, Europe, and China.

“We come up with our own original ideas,” he says, “but we also look at competitors. It’s both.”

Some EHX designs, he notes, have proven harder to replicate. The B9 and MEL9 pedals, which transform guitar signals into organ and Mellotron-style sounds, remain uniquely Electro-Harmonix achievements. The POG (Polyphonic Octave Generator) series is another standout, used by countless players across genres.

“If you really want to do something new,” Matthews says, “it’s got to be digital. There’s not too much new you can do in analog except add features.”

And yet, surprises still happen. Matthews mentions the Atomic Cluster, a chaotic, joyfully unhinged fuzz, as a recent example.

“I didn’t think there’d be much to it,” he admits. “But we’ve gotten a huge number of orders. That was a surprise.”

One interesting exception to Electro-Harmonix’s global dealer model is Australia, where the brand works exclusively with Melbourne-based Vibe Music.

“Australia’s so big,” Matthews says. “Freight, service, repairs—it’s complicated.”

Vibe Music’s Joseph Lamberti, whose father built the highly regarded Rex Bass King amplifiers, is someone Matthews clearly respects.

“He came up early,” Matthews says. “He can service and repair most everything. He does a great job for us.”

There’s a nice symmetry here. Australia, like the UK, once had to invent its own versions of American gear simply because we couldn’t get the real thing. That DIY spirit still matters, and it’s fitting that Electro-Harmonix, a company built on resourcefulness, values that so highly.

Any conversation about Electro-Harmonix inevitably circles back to the Big Muff. It’s not just a pedal, it’s a cultural artefact. And its origins trace back to Matthews’ unlikely proximity to a young Jimi Hendrix.

While still in college, Matthews promoted touring acts, including Chuck Berry. One booking led to another, and eventually to Curtis Knight and the Squires featuring a guitarist named Jimmy James.

“That guy was Jimi Hendrix,” Matthews says.

They became friends. Matthews visited Hendrix in his tiny Times Square hotel room, talked music, and watched him develop his phrasing-based vocal style.

“He told me, ‘I can’t sing,’” Matthews recalls. “I said, ‘Look at Jagger and Dylan. They don’t sing—they phrase.’”

Hendrix took that idea and ran with it.

When Hendrix became famous, Matthews wanted to give everyday guitarists a way to access that kind of sound. Working with Bell Labs engineer Bob Moog, Matthews helped refine a cascading gain circuit, carefully rolling off distortion at key points.

“That became the Big Muff,” he says.

Like many players my age, my Big Muff awakening came via the ’90s. Smashing Pumpkins, Dinosaur Jr, shoegaze walls of sound—all of it traced back to that box.

Billy Corgan’s version of the Big Muff, Matthews explains, was actually a different circuit.

“Our guys developed a simpler version using op-amps,” he says. “It was rougher sounding.”

Corgan accidentally bought one and loved it.

“I personally didn’t,” Matthews admits. “But what matters is what sells.”

That pragmatic mindset is central to Electro-Harmonix’s longevity. Sales fund designers. Designers create new ideas. And financial stability allows the company to weather tough times.

“We’re very strong financially now,” Matthews says. “That’s important.”

Electro-Harmonix is now a legacy brand in the truest sense. People tattoo the logo onto their bodies. They build careers around its pedals. They form emotional attachments to pieces of metal and circuitry. Matthews is aware of it and amused by it. “Have you seen all the tattoos?” he asks. There are hundreds!”

Despite turning 84, Matthews doesn’t dwell on age. “I don’t really celebrate birthdays,” he says. “To me, it’s just another day.”

That mindset makes sense. Electro-Harmonix isn’t a nostalgia act. It’s a working, evolving company—still releasing products, still surprising itself, still fighting through whatever the world throws at it. As Matthews signs off our conversation with a cheerful “rock and roll,” it’s clear that this isn’t a man reflecting on a finished story. He’s still writing it.

For local enquiries on Electro-Harmonix, visit Vibe Music.