An exposé into sound production and music education

The beauty of music and art is that there are no rules. Anyone can have a go without formal qualification, and even if they fail per se, they’ve still made something. So if anyone can make anything – why bother with formal higher education in music or audio? This is a pretty hotly debated topic, with professionals hailing from a variety of backgrounds all weighing in. For the modern Producer/Artist/Engineer, there is a decision to be made, whether that be a traditional internship career progression, being completely self-taught, or a formal further education in colleges and music schools.

It’s important to make a case for all three avenues and then some, as any way you approach it, there’s pros and cons. What can you gain from an audio school that you can’t get in the real world? Is there anything that can’t be taught? Is the financial commitment really worth the end result? Let’s dive in.

Summary:

- Higher education audio schools can be beneficial for those looking to learn about the technical side of recording/mixing/mastering as well as provide a leg up if you’re looking for internships.

- Deciding to not go to audio school will mean you have your time free to create music, which is great for if you’re an artist and want to leave the job of audio engineering up to someone else.

- There’s something to be said for making it on your own, but it may be quite challenging to make it in an industry that was previously based around earning your stripes working as an entry level tape operator.

Read up on all the latest interviews, features and columns here.

Firstly it’s probably important to break down the fundamental differences between music (ie the conception, development and arrangement of a musical idea in the artistic sense) and audio (the mostly dry, overtly scientific processes that allows us to capture and control this comparatively freeform expression and present it as something coherent and replicable in the mechanical sense.)

In the earliest days of modern recording practise (ie. the period directly after the second world war), Musicians and Engineers were perceived as two completely separate and isolated entities, often identified by the presence of a white lab coat, which the engineers wore to denote their commitment to science. It was very much church and state, as the Art and Science were kept as separate as possible.

To become an audio professional back then would generally require a technical background in Military Comms, Broadcast or at the very least, hands on experience in Ham Radio or operating phonograph cutting equipment like lathes and presses. It was very much a technical trade rooted in science, rather than the artistic pursuit it is today.

Engineers were expected to be equal parts, studio lackey, acoustician, electrician and highly evolved maintenance man. The word ‘Engineer’ was used in much the same manner that we call train drivers ‘Engineers’.

More than just the basic operation of the equipment, there was the expectation that if the situation called for it, this person could break out the tools and fix or modify equipment on the fly, performing necessary maintenance or treating complex electro-acoustic anomalies, all with a minimum amount of downtime. Amongst these Engineers, efficiency and process were sacrosanct, and they prided themselves on employing techniques firmly rooted in science and the logistics of streamline recording workflows in order to craft great recordings.

Specialist titles like Recording Engineer, Mix Engineer and Mastering Engineer started to emerge in order to delineate one role from another. In 1948, they even formed their own professional body, (the Audio Engineering Society, which still exists to this day) as a means to legitimise and standardise the technical elements of what was a burgeoning and pioneering industry.

As the broader music industry began to truly boom in the 50’s and 60’s and more and more labels began popping up, there existed a worldwide shortage of this kind of traditional, hands-on Technical Engineer.

The global hunger for recorded music meant that the major labels would be expanding operations, building larger recording complexes (often with A,B and C rooms) and often requiring separate teams for each. This meant that there would have to be some kind of system in place, to provide a constant flow of engineering talent to these new studios and hence the roles of Assistant Engineer, Tape Op and Studio intern were created as a path for novice engineers to enter the studio system and learn at the feet of seasoned pros, earning their stripes and working their way up the ladder.

For the majors, studios were big business, big infrastructure, big overheads and (with the right tune and some clever marketing) big returns, and this apprentice system ensured that they would have a sufficient and skilled workforce to keep up this breakneck pace.

At the other end of town, the glut of fledgling independent labels were doing their best to keep their in-house engineers working through the night, while also keeping production costs to a minimum.

This in turn meant heaping extra responsibilities onto specialist engineers and Studio personnel and thus, the subtle erosion of traditional studio roles began (while the pay remained largely the same).

Just a decade on from the hardline, largely fixed responsibilities that defined these varying technical skill sets, by the late 60’s we had producers setting up microphones, Recording engineers moonlighting as Mix Engineers and (gasp) Artists moonlighting as Engineers.

The fact that all of this coincided with the emergence of psychedelic rock, stompboxes and Artists actively taking a greater hand in the sound of their recordings, meant that the new recording landscape bore little resemblance to the tried and tested Studio workflows that had come before (for better or worse).

On the one hand, this new landscape afforded artists an unprecedented amount of creative freedom in the studio. On the other, we had the breaking down of a system that was optimised for the most efficient, highest quality recordings to be put into production as quickly as possible.

Thanks largely to the Beatles (among others) major labels were now competing to offer more and more ‘creative control’ to their flagship artists, while the fledgling Independent labels would allow for plenty of opportunity for ‘outsider’ music to be distributed and heard around the world (often with scant regard for Audio quality or AES approved levels of fidelity.)

The eventual emergence of home recording technologies like the Tascam Portastudio or Fostex R8, meant that artists could now do a fair portion of the labour themselves away from the studio (to varying results and to mostly open ended deadlines.)

Even then, these home recordings would often need to be salvaged by a team of Pro Engineers, in order to be pressed onto vinyl or receive radio play of any kind. This was rarely talked about as it lacked a certain myth making and marketing charm- even if in reality there was indeed a Professional working tirelessly behind the scenes to make it right (looking at you, Mr. Springsteen).

It’s from this tradition (and the eventual emergence of the DAW) that this recent archetype of the entirely self-sufficient, modern producer/engineer/musician has its roots.

There’s something to be said for artists and creatives that break and bend the rules, merge genres, and generally approach music with a left-of-centre attitude. This kind of pioneering and punk attitude has always pushed the industry, art and process forward, but it also begs the important question: How do we break the rules if we don’t know them?

Audio schools provide an unparalleled ground level understanding to build on, and I don’t think that can be understated. As audio engineers and producers who are often hired to serve a client and bring their ideas and music to life, we need to be ready to create any sound that the artist may want to achieve with whatever mediums they’d like to work in, thus we need a textbook understanding of these principles and workflows in order to work efficiently serve the client as best as we can.

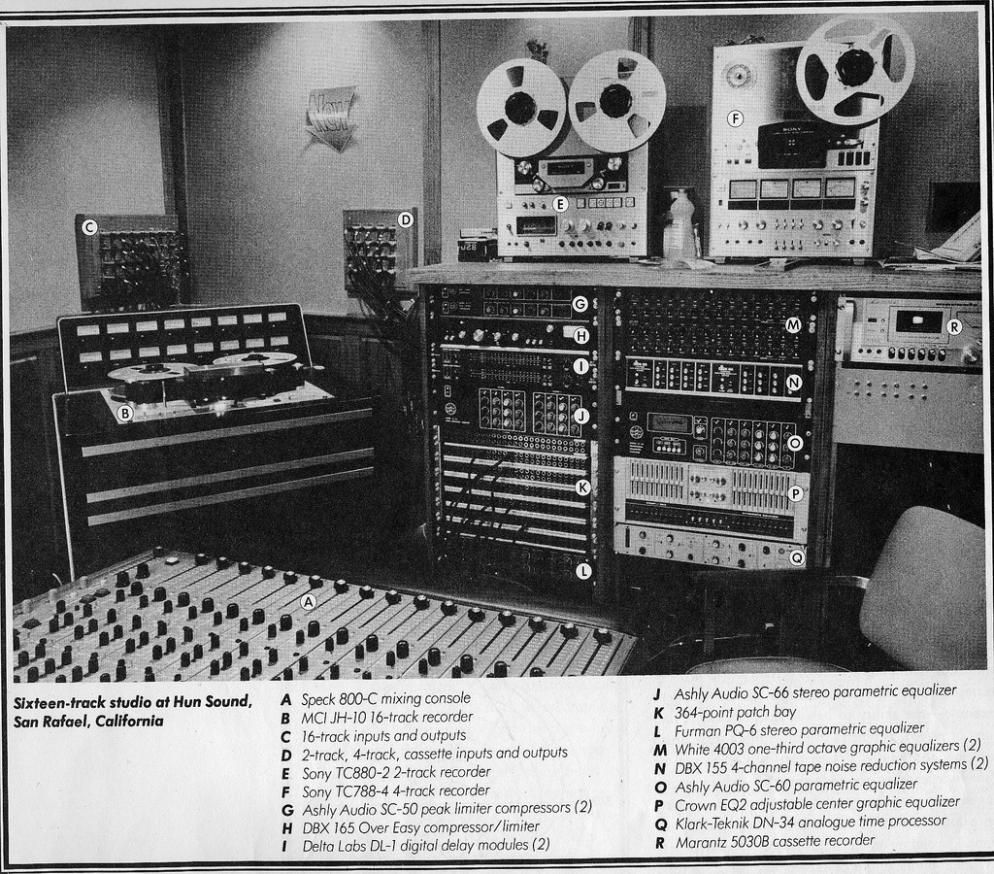

Audio schools will give you an unparalleled, broad understanding of console signal flow such as auxiliaries and split console monitoring, tape machine operation, microphone and preamp selection as well as mic placement, compression and EQ theory to assist you in making critical decisions on the fly. It will also ensure you are across multiple DAWs and tech advancements and how to augment them with other more traditional workflows.

For the artist looking for greater control of their sonic signature, having a basic understanding of the physics of sound and electro-acoustics can be the perfect gateway into a level of expression far beyond mere composition alone. It can also open a pandora’s box that may mean less time composing/playing and more time charting the sound absorption coefficients of egg cartons. While the internet can provide an ever-growing list of tips, tricks and advice, when it comes to learning these things and retaining the skillset long term, it’s hard to go past the audio school.

Even with the ocean of information out there, a formal education assists you in weeding out the good advice from the bad, based on the fundamental understanding developed in your formal, technical education. There is also a lot to be said for being in contact with the actual hardware that is at the core of so much of modern in the box workflow, even just as a reference point towards understanding it’s operation in the context of a real world recording situation.

Admittedly, once you have a basic understanding of audio, you’ll quickly realise that there are some things audio schools can’t teach: charm, personality management and for want of a better term the ‘human’ element of the music making process.

With regards to the uneducated, there is a certain magic that comes with creating music without knowing ‘the rules’ and the propensity this has for creating ‘Happy accidents’ (even if it may require an Audio Professional or mastering engineer to reign them in down the line).

Things may technically be over-compressed but bring forward an element of the performance that would otherwise go unnoticed. A vocal may be left un-EQ’d, forcing you to sculpt the sounds around it to make it all fit, and leaving an emotive, dynamic vocal take largely unprocessed and true to the singer’s voice. Guitars might be recorded out of phase with multiple microphones, leaving your peers wondering which pedal you used to achieve that oh-so-imperfect phaser sound in the intro.

There’s a case to be made for happy accidents, and I think both formal education and non formal education can assist in this. A formal education provides the groundwork to understand why sources sound the way they do, how to manipulate and push them to their limits, while an uneducated (per se) producer may find something entirely different because they’re not operating within any construct but their own.

On the other hand, part of sculpting the sonic palette is keeping the project on course, whilst maintaining the excitement and thrill in the studio that inspires those ‘magical’ takes, whether they come from you or a client. What an audio school can teach you (on top of the obvious sonic lessons) are hard skills like DAW file management, professional data entry and how to back up your sessions safely, so those happy accidents can find their way onto actual records which will in turn be played back with some kind of sonic consistency and baseline level of fidelity.

Formal audio training is also invaluable to time management and helping one develop a sense of foreseeing potential technical problems and providing you with answers on how to fix them before it takes its toll on creative morale and momentum. While it is incredibly difficult to teach someone how to earn a band’s trust, maintain momentum and ultimately manage a project end to end, it’s far more straightforward, teaching them the professional and technical habits that can elicit such a response. It’s this kind of learned professionalism that Audio schools absolutely excel at.

On top of this, they are also the single best avenue to facilitate internships, assistant gigs and an opportunity to prove yourself to the right people. This experience in the field is literally worth its weight in gold and is probably one of the single strongest arguments for audio schools as a whole. The things you can learn about workflow, mic placement, troubleshooting etc will save you hours of your life regardless of whether you are producing for yourself or working with others in a professional setting.

Alternately, if you decide that the ‘Art’ is the end goal (and not the capture and reproduction), then maybe your time could be better spent experimenting with arrangement and song structure, breaking down your artistic habits and developing your performance skills to a degree that you are bringing your own kind of professionalism to the record making process, one that makes space for collaboration with someone who has dedicated this same amount of time to studying the dry, science of record making as you have the creative, ethereal side? Like they always say, teamwork makes the dream work.

All it takes is a realistic appraisal of what kind of artist or audio professional (or something in between) you are best suited to and the most direct, and obvious path to getting there. Like all creative pursuits (Garageband excluded), there are no templates!

For more information on all things audio, head to the Audio Engineer Society.