For someone unfamiliar, mixing might seem like a fairly straightforward process of getting the levels right, making sure the vocals stand out and the drums and bass sit back appropriately. But the responsibility of the mix engineer is far greater than just the technical specifics.

“The thing about a mix is that it can still be technically correct, yet completely wrong,” says Moro. “A wrong mix fails to connect with a listener or attract radio attention. The right mix gives the listener feelings.”

The mixing process will vary depending on the nature of the individual song, who the implied listener is, and how much involvement the artist or producer has in the process. But in all cases the song should already have the right vibe before any mixing is done.

“When artists reference other songs, very often the thing they are drawn to is compositional and that’s tricky to do in mixing,” Moro says. “For example, if someone references some upbeat indie pop song, but the melodies they are singing are minor pentatonic, it’s going to feel more bluesy and R&B.

“I like to know if there are specific things an artist loves or dislikes before starting work. That way I can factor it into my decision-making. I’ll still go with my gut on some things, knowing that if the artist doesn’t vibe with it I can revert it in an instant. I’d never spend hours trying an idea that the artist may or may not like. Ideas should be able to be tested within a few minutes tops, that way I can still be objective.”

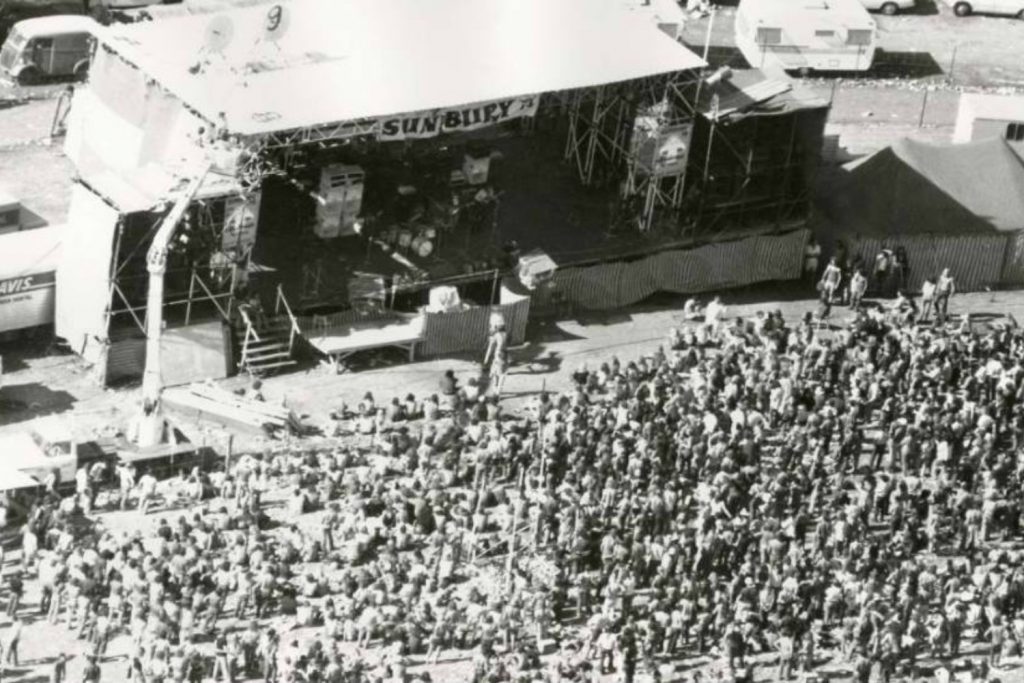

The labour intensity of mixing will vary based on the number of tracks in the multi-track session. The genre of music is also going to have an impact. For instance, a hip hop song with a programmed beat is going to differ from a live recording of a punk band.

“Hip hop artists spend so much time finding their sounds and making their beats, you usually get the vibe right away,” Moro says. “The process might be more about finding the right saturation for the sounds and getting that analogue magic.

“It’s funny though, sometimes a song with 80 tracks might take two hours to be 90% mixed, while a song with piano, voice, a harmony and a cello might take three hours. If the song has a lot of layers but they are well arranged, the mix can come together quite quickly. If there are only a few tracks, I have to do a lot more to create contrast from verse to chorus, and to encourage interest throughout the song.”

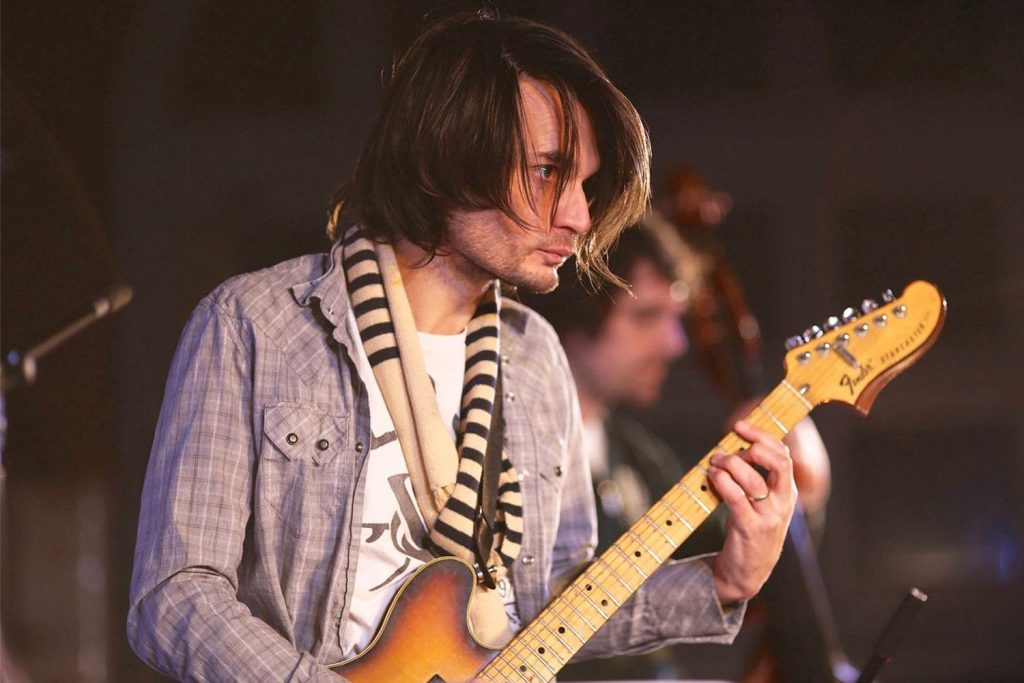

There are some recurrent techniques Moro applies when mixing live instrumentation such as drums, bass, keyboards and guitars.

“I’ll usually be augmenting live drums with samples. Most of the live drum samples I use I personally recorded [find them at indiedrums.com]. I often use stereo room samples in choruses so that the drums suddenly get wider. It’s a nice little trick to add subtle width.

“With bass, I tend to prefer DIs with amp simulators over mics on cabinets. The reason is I can get the bass to sit much better, with so many tonal options. I use Amplitube and Eleven MkII. Switching cabs and mics and mic position in the plugin can get the bass to sit in the sweet spot.

“On pianos I’ll usually add some sort of saturation. I’m a fan of Soundtoys Decapitator for this. With guitars the tone is usually pretty solid, but I may add some extra saturation, reverb, maybe some delay.”

When you think of mixing, the image that comes to mind is of someone sitting behind a massive desk, pulling up faders and soloing particular instruments (think Classic Albums). The mix engineer has a lot of power, as the mix can change the entire perception of the song.

“This is one of the most concerning parts of the DIY approach. There are a lot of great songs that are getting underwhelming results because the mix is failing. I guess like anything, the first song you mix won’t be as good as the 20th, 50th or 100th,” Moro says.

The essence of a song varies – some rely on their melodic structure, while others centre on dynamics, rhythm and instrumental motifs. As a mixer, Moro’s goal is to reinforce the emotion behind a song.

“For example, if a song is supposed to feel lonely, designing a reverb that makes a vocal feel isolated and alone is better than a dry vocal that sounds just cool. Just as a dry vocal is going to be the right choice when it’s supposed to feel like the singer is vulnerable, close and connected, no matter how cool that new reverb plugin might sound on it. You have to reinforce the emotions you’re trying to give the listener.”

Balancing lead vocals can be the most troublesome part of the mixing process, especially if the vocal is very dynamic or if you can hear the sound of the room in the recording.

“If I’m working with a vocal that was recorded at home, I might hear the sound of the room. With more compression – and I love compression – that room sound is going to get louder, and louder. The room is natural reverb and reverb is how we place sounds front to back on the sound stage. No reverb is front of stage, drenched in reverb is way down the back. Now, if I’m hearing the room in the mic, I can’t get the vocal to sit right at the front of the stage. Sure there are little tricks, but these tricks are never as good as getting the sound right at the mic.”

Mixing isn’t the final part of the process, but generally you want the mixed song to sound fit for radio or ready to be pressed to vinyl.

“These days with so much DIY, I think there tends to be an expectation that mastering is where you get the magic. Think of the mix as the product. At the end of the mixing process, the song should have all of the excitement and feeling it needs to connect with listeners. It’s like the mix is the meal, and mastering is the garnish and plating up.

“I’d take an experienced mixer’s work, self-mastered, over a DIY mix, pro-mastered. And that’s just because all of the parts come together in the mix. If the vocals really need to be dry, that can’t be done in mastering. If the guitar needs to be muted, that has to be done in the mix.

“Just like every part of the process, things get exciting when you’ve got the best team across each part. A killer mix, mastered by a pro mastering engineer is going to sound awesome.”

Find out more about Simon’s work at ninetynine100.com