The ultimate DJ battle from Jamaica to the world.

Born in Jamaica and then exported around the world, the sound clash is one of the more unique live music competitions today – and for good reason. Live music competitions are not an unfamiliar concept. Bands and artists have battled it out throughout musical history, competing for prizes, fame, or simply the chance to be crowned champion. It’s the latter accolade that drives a culture whose origins go back decades, one which sees some of the most talented DJs fight to be declared the winner.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

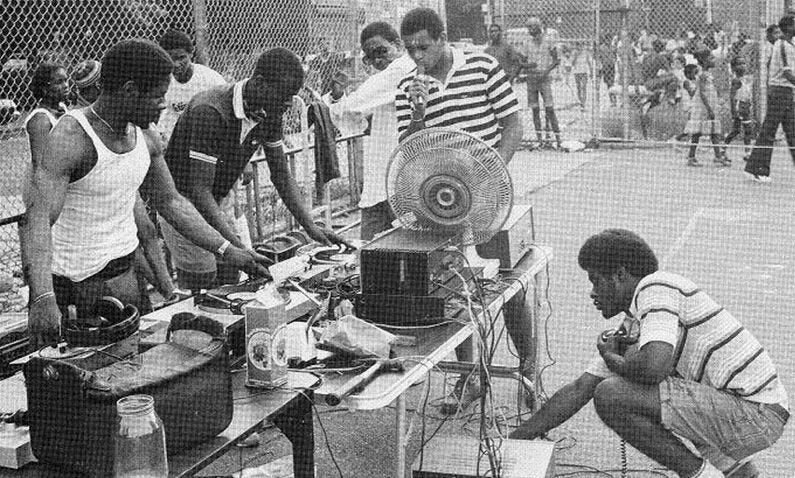

The sound clash began on the streets of Kingston, Jamaica, in the 1950s. Because very few people had the money to buy records, the main way that people were introduced to new music was either in dancehalls or at street parties. Therefore whoever owned and operated the portable sound systems was in a position of influence when it came to setting musical trends.

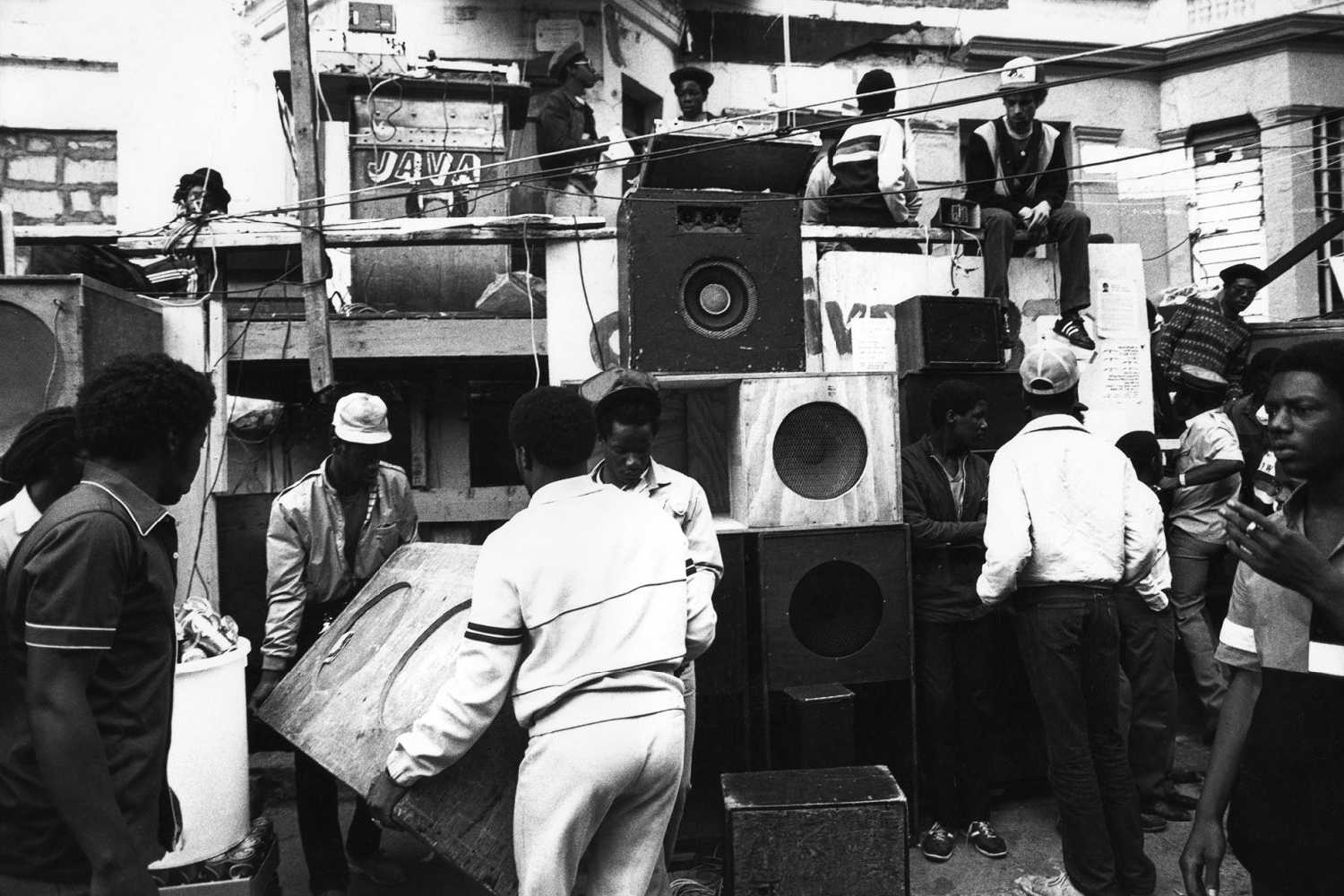

Starting out as an informal rivalry, the sound clash developed as the result of a natural instinct to compete with another sound system set up in close proximity to your own. Sound systems were led by people such as Tom Wong, Duke Reid, and Sir Coxsone and began with stacks of speakers set up, playing US R&B records. The competition involved two or more sound systems battling to produce the best selections and performance to be crowned victorious by the watching crowd.

Sound system culture is competitive at heart, right down to the size of a crew’s speakers, which have been known to total 12 feet high and wide. Predating the foundation of dancehall, reggae, and ska, the sound system soon travelled overseas with Jamaican immigrants in the 1950s and 1960s. The UK embraced the culture with Lloyd Coxsone’s Sir Coxsone Outernational becoming one of the country’s most well-known early systems, with others such as Jah Shaka, Channel One, and Saxon Studio International following close behind.

Lloyd Coxsone’s Sir Coxsone Outernational

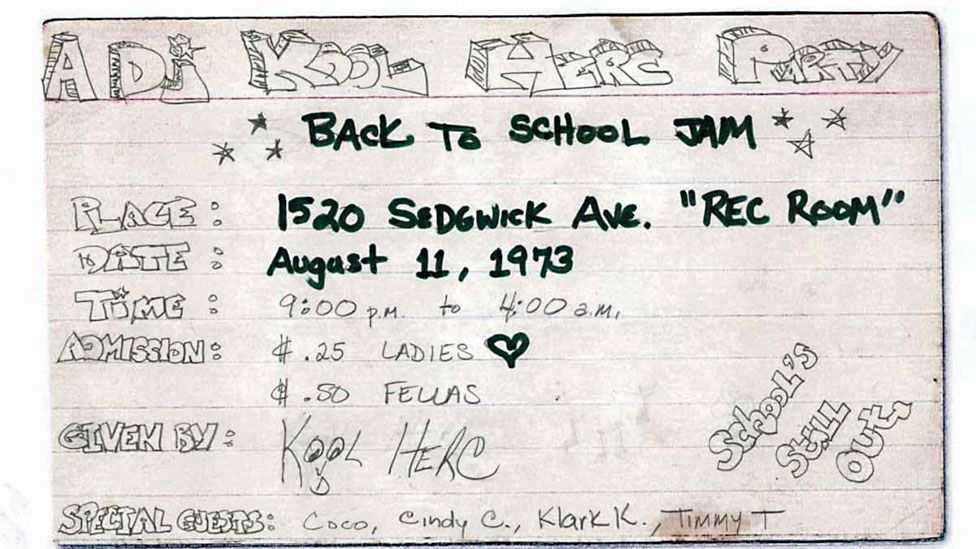

Meanwhile, Jamaican-born DJ Kool Herc moved to the US and set up his own sound system – Herculords – and the turntable techniques that he developed there are considered by many to be the beginnings of hip hop.

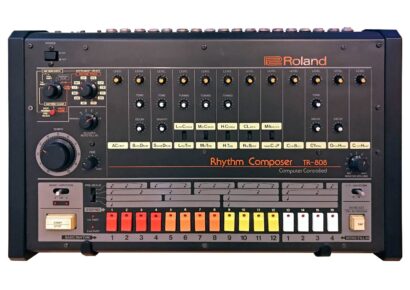

Legendary Jamaican producer Coxsonne Dodd pioneered the idea of releasing a ‘riddim’ version of a song in the mid-’60s by removing some of the melodic elements of a track, such as the horn section. And in 1968 the owner of a local sound system known as King Tubby took this idea even further by making instrumental versions of songs and using these to extend the tracks when played live by the DJs. This proved to be so popular that by 1970 it had become common practice to issue an instrumental version as the B-side of a single, and can be seen as the genesis of dub music.

Throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s the role of the DJ became as important as the music, a development that affected the sound clash with the new convention of adding an instrumental B-side to a record for the DJ.

The original format in Jamaica was based on drowning out your competitor in volume, thus requiring physically bigger and more powerful speakers, but when the sound clashes came to England they soon moved indoors. Consequently, it changed to become more of a formal competition, with different DJs playing after one another and the crowd selecting the winner.

Yellowman, Tenor Saw, and Burro Banton

The culture progressed into the ‘80s with the arrival of the dancehall and prominent DJs such as Yellowman, Tenor Saw, and Burro Banton. Live vocals and MCs were introduced to clashes, while the trend of producers releasing clash tracks wasn’t well received by the sound clash community. To avoid the issue, DJs began including the name of their sound system in songs to deter producers from releasing the tracks as their own.

Sound clashes continued to grow in popularity into the ‘90s with the arrival of a new format called ‘World Clash’. This system saw countries from around the world competing in a clash at one location. The first World Clash is believed to be the one held in London in 1993 between Bodyguard (Jamaica), Saxon (UK), Coxsone (UK), and Afrique (USA), ending with a controversial win by Bodyguard.

The World Clash introduced a structure to the traditional clash, with a referee and rounds similar to boxing, however, many in the clash community felt this was a poor imitation of a real clash.

While the values of sound clashes remain the same in their modern form, some technical aspects have changed. In an interview with Red Bull, sound system veteran David Rodigan explained that qualifying to enter in a clash today means “you should have a number of customised recordings made especially for you by artists who are renowned, and those artists must call your name in the recording”.

“The rules have stayed pretty much the same since clash started,” said Rodigan.

“An open round, then elimination, then another elimination, until you’re down to playing between two sounds. Those two sounds then run through a one-for-one, playing one tune each, with the audience deciding the best track. The first sound system to get to 10 – with the audience deciding who has the best dubs – is the winner. All these dubs have to have your name in it – they have to have been made for you.”

Red Bull Culture Clash

The sound clash was maintained through annual events held throughout the world. In particular, the Red Bull Culture Clash which ensured the competition continued its long history with new clashes. The artists battled for glory and in doing so, maintained a culture that spans decades, continents, and a whole lot of records.

Sound clashes in their original outdoor form are still very much alive both in Jamaica and around the world, often being held in carnivals in the UK. The Notting Hill Carnival is London’s biggest street party and hosts sound systems every year.

Check out Red Bull’s list of the five best Culture Clash performances.