Like every artist and manager, I’ve been guilty of taking them for granted. I’ve assumed they were bulletproof and capable of doing things that were clearly impossible. Even if the truck loaded with the crew and equipment drove at 300 kilometres an hour, they were not going to get from Gig A to Gig B in ten hours.

Over the years I’ve drunk far too much beer with roadies and bought far too many drugs from them. A good roadie always knows how and where to score. And they score good. Some of the crew from those days are still my friends. I’ve only lost one friend to the rigours of the roadie world – and that was a woman trying her hand in the very blokey world of the mid-1980s Australian road crew. Genevieve Farmer was killed in a car accident near Coff’s Harbour while working for The Johnnys.

Really, I’m lucky to have known just one roadie who’s lost their life. Given the hundreds of thousands of kilometres driven by roadies over the decades, often on less-than-ideal roads and frequently with a bloodstream fuelled by alcohol and amphetamines – and just one or two (or three) joints – it’s astonishing that the road toll has been so low. The real carnage has been in the area of mental health. And it’s frightening. Very frightening.

When I was researching my biography of Michael Gudinski, I received invaluable assistance about the Melbourne music scene in the late 1960s and early 1970s from Adrian Anderson, who had worked extensively as a roadie. During one conversation he told me about the Australian Road Crew Association (ARCA), which was launched in 2013 by working and retired roadies to try to stall the staggering rate of suicide among former roadies. In basic terms, Australian road crew members suicide at four to five times the national rate. Internationally the rate is nowhere near as high.

Why have legions of Australian roadies been ending their own lives? There are some basic reasons. Physical incapacity. Poverty. Mental illness. Decreased demand. A changing workplace. A lot of the older generation began working in the business in their late teens. There was no occupational health and safety, and no training. They spent 10 or 20 years pushing their bodies to breaking point. And their bodies did break. Many former roadies suffer significant back and muscular-skeletal problems. They’ve had multiple surgeries, and body parts replaced. They live with chronic pain. Too many roadies have passed away simply through neglect of their health, or because they lack the means to get proper medical attention.

Sometimes the work just dries up. The artist a roadie has been committed to moves on, or a band breaks up. The Australian live scene is not what it was in the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s and even into the ’90s. There is less work, and more competition for it. Until recent times there was no superannuation for roadies. Some roadies were paid comparatively well for the work they did, others not so well. There is still no holiday pay. Beyond watching great rock’n’roll, and a lifestyle that many enjoyed, there were no other benefits. Except maybe a sense of purpose, and of family and belonging. But when it’s all over, that can be lost too. For some, there is no one waiting at home, or no home at all.

Like the musicians they work for, roadies have a tendency to overuse alcohol, stimulants and other drugs. Often whatever they can get their hands on. Ultimately, though, using stimulants for short-term escapes or as pick-me-ups often masks deep-seated issues, and some roadies put off dealing with those issues for years and years. It’s an understatement but years on the road makes it hard to maintain long-term relationships. Find a former roadie who has a stable, a longstanding relationship and you’ve found a roadie who is probably not in danger of self-harm. Sadly, there aren’t many like that.

Then there’s the issue of gaining other employment. Sure, there’s security work or corporate events for some, but for others many doors are closed because they have no recognised qualifications. “Mate, I can get Guns N’ Roses around the country, onstage and not missing a gig – and apparently I’m not qualified to do anything,” said one former roadie.

The tragic suicide of much loved crew guy Gerry Georgettis 10 years ago galvanised the roadie community, and led to the formation of ARCA. The mantra of the organisation is that a roadie should call another roadie each week and check in on them, and this – along with financial assistance, in conjunction with the Support Act organisation – has dramatically reduced the suicide rate. Former roadies are learning that that they’re not alone.

Why did I decide to write the stories of Australian roadies? Partly because I know and love the world they inhabit. I was stunned by the suicides, and acutely aware that with each passing we lost not only a great individual but a key part of Australian music and popular culture history. No one was recording oral histories with these roadies. No one was preserving their memories and stories – some of them hysterically funny, others beyond poignant, the majority of them – let’s not kid ourselves – embellished from years and years of retelling.

Roadies know Australian music history in ways that no one else does. Not even the artists who make the music. Roadies know the real road stories, the successes, the disasters, the fuck-ups and the triumphs. They speak a language that is distinctly Australian. It’s direct, and often laden with expletives. And they tell a secret history of music in this country – from small pub bands to the mainstream success stories and the international tourists. Artists are only at their own gigs; roadies are at everybody’s gigs. That makes them custodians of the history of Australian and international rock’n’roll.

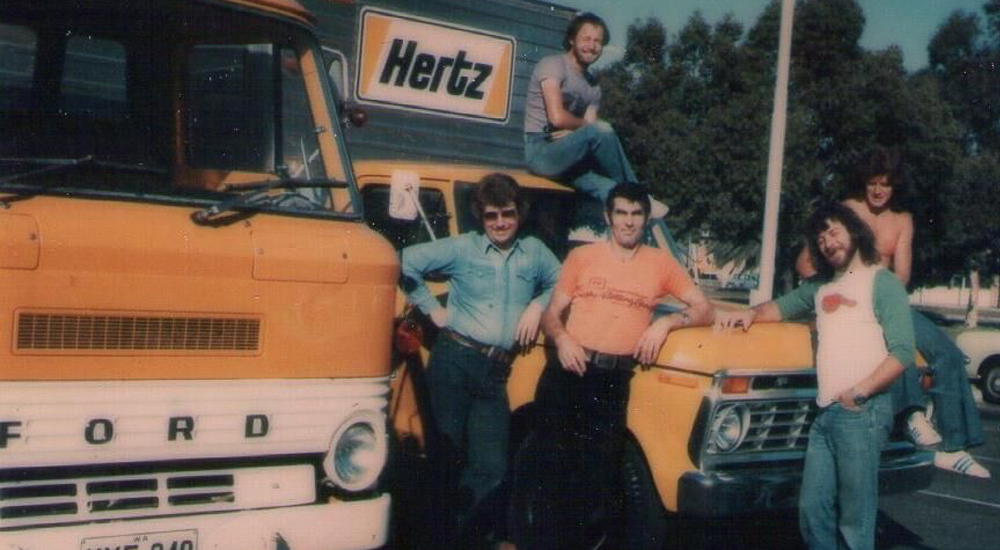

The roadies featured in this book have worked with dozens, often hundreds, of artists, across all musical styles. There is nothing they haven’t seen, fixed, set up or packed up. The world of the roadie is unique: it’s about making musicians look and sound as good as they possibly can, night after night after night. Roadies are great story tellers. They have hundreds and hundreds (make that thousands) of yarns – almost all of them embellished to some degree by years of retelling. Theirs is in the classic oral history tradition, apocryphal yarns passed along in seedy bars, backstage, in hotel rooms and cramped trucks. Many of those stories and shared reminiscences are in my book. Of course hundreds of them aren’t.

My book can’t hope to feature every Australian roadie, or tell all their stories. They could probably fill ten thick volumes and still only touch the surface. What I have attempted to do is bring you into the world of some astonishing characters, and let them have a yarn about their journey on the road with Australian and international artists. It isn’t definitive, but I have no doubt that it is representative.

By the end of my book, I hope you never view a rock’n’roll concert the same way again. You’ll be looking around for the road crew. You’ll realise just what has taken place behind the scenes so you could witness this musical event – and what will continue to take place long after you’ve gone home. One roadie I spoke to for the book commented that everyone admires a Ferarri – it looks magnificent and runs like a dream. But the real essence of a Ferrari is the engine under the bonnet. Without that, it’s just a good-looking piece of metal. Road crew are the engine under the bonnet of every rock’n’roll performer.

Roadies – the Secret History of Australian Rock’n’Roll by Stuart Coupe is out today through Hachette Australia.