A personal account of a thriving career in the studio

Producer, engineer, musician, composer, sound designer, and whatever other hat you can possibly wear in a studio still doesn’t cover the breadth of expertise that encompasses Gregg Leonard.

Maintaining the human element of remote collaboration is a task we still find problematic and difficult despite the great advances we’ve made since the onset of the pandemic.

A remote collaborator ahead of his time, we caught up with Gregg to discuss the vital aspects and the changes in the workflow, as well as his hottest production tips in his years of experience.

Read up on all the latest interviews here.

Can you briefly tell us a little bit about yourself? What has your professional journey looked like to this point and how did you get started?

I was born in the Midwest of the US in Ohio and started playing professionally in clubs at age 16. Because it was an industrial part of the country with close proximity to cities such as Detroit and Chicago, the music culture was a rich tapestry of styles ranging from country, soul, jazz, the blues, funk, and of course rock ‘n’ roll. I was lucky enough to be exposed to all of that as well as having a chance to to cut my teeth by playing with accomplished older musicians.

Eventually I started focusing more on recording and production, learning the art of both in various Detroit studios before co-founding a studio in Ann Arbor Michigan.

At this time I also started working in the film and media industry, first in the music supervision and sync world and then scoring. A couple of film projects brought me to Australia for the first time a few years ago and have brought long standing collaborative relationships with many Aussie musos.

I have spent the last 14 years in Los Angeles working as a composer, sound designer, producer and music supervisor.

Working remotely feels like something everyone’s gotten across well and truly by now, but you’ve been doing it well before the pandemic! What was the typical workflow like for you in the early days?

All the way back in 2005, while still living in Ann Arbor, I scored an Australian film titled Feed. As you can imagine, the internet was a lot less robust in those days and moving data around, especially large video files and multi track audio deliverables, required patience and careful planning. This was also pre-Zoom, Whatsapp etc. Pre smart phone even, so managing logistics and workflow was tricky. Even with compressed video files, I would have to download for hours, then score to picture before sending tracks to the editing room in Sydney for approval. A lot of late nights trying to navigate the 17-hour time difference!

I produced a few tracks for the soundtrack using some great Aussie indie bands from that time. I had been in Sydney for part of the production and had the opportunity to cut tracks there before overdubbing and mixing them back in Detroit and Ann Arbor.

How do you maintain the human element of a production when working like that? Have people been reluctant over the journey for that reason?

Film or media music lends itself more easily to siloed work as long as there is open communication and the ability to respond quickly and efficiently. Most of the session players I use for score work are used to working remotely and are well equipped to do so.

In terms of working with a band or an artist, many artists are now quite comfortable with a modular creative process and workflow. Many have actually known no other way. I am however, very much a proponent of recording live musicians and having players interacting together whenever possible. I think real magic can happen if you can cut at least the rhythm beds that way. I recently finished producing a project with a talented Los Angeles-based artist for which I assembled a fantastic rhythm section, cut the basics live in a great sound room, and have had players from Nashville, LA, and Australia contributing overdubs remotely. The best of both worlds.

Fast forward to now, how do you engage remote collaborators with the streamlined technology that we have available for us?

Over the past couple of years, remote realtime collaborative platforms have come of age. The pandemic certainly accelerated that. Providing the internet is decent, I can conduct realtime mixing or even recording sessions remotely.

Recently I had a session where the singer was in New York, my client was in San Francisco, and I was overseeing it all from regional New South Wales. It’s a long way from even a handful of years ago! Even setting the realtime aspect aside, powerful, inexpensive recording equipment allows many talented people to work remotely. I have a database of great musicians from all over the world I can bring into a project. For example while I was still in LA, I was able to bring a great Melbourne based singer named Susie Ahern onto a project I was working on.

In your own words, please describe your average production workflow and setup. What are you running gear wise? Do you have a space that you work out of?

Besides a handful of good mics and mic pres, I’m pretty much fully in the box these days and primarily use Pro Tools. I was fortunate enough to come up in the era of analog recording but I’m now able to to make very analog-sounding recordings and mixes in the digital realm.

If I do need a room to cut live musicians or do an in person mix, there are a few choice spots in LA I can use if I’m Stateside. As I’m now living in Australia full time, I have started looking into locations here.

In terms of workflow, if I am producing a track for an artist or band, I’m a firm believer in pre-production, hopefully in person if possible. We can then do everything from basic to overdubs and mixing remotely if needed. Otherwise, I love to get in a room with a band and see if we can get some magic happening!

Film and media work usually starts with a spotting session with the director and trying to establish the music themes and language for the project. From there it’s hold on and wait for some inspiration to hit!

Do you tend to work in short bursts or marathon sessions? Where do you usually start? How do you know when something is finished? Are there any production techniques that you feel are an important part of your sound or process?

I have certainly done my share of marathon sessions and occasionally still pull some long hours if there is a deadline looming. I do like to pace things for shorter, more efficient sessions if possible. Especially when working with musicians so people don’t get burnt out and slip into diminishing results. The whole process starts with the song and discovering with the artist the best way to distill their intention and vision into making a great recording.

A great thing about digital, non-linear recording is that you have almost endless possibilities and ability to fine tune a mix or performance. However, this is also the potential downside for many reasons. Having learned the ropes in the analog age when irreversible decisions were part of the process, I developed a good sense of when to call things done and how to judge a performance. Ultimately, a great recording which will touch people and stand the test of time is usually not one which has been tuned and tweaked to perfection, but hopefully one that captures the beauty of honest human expression.

What advice would you give to someone at any point in their music journey?

We are in a very different and rapidly evolving environment from when I started. On one level, music also occupies a different place in mass culture than during what many refer to as its modern renaissance period from the ’50s through the mid noughties. In that period it evolved into a large-scale business and in many ways drove the culture.

The business model has been massively disrupted and it is still shaking out as to how to develop revenue streams sufficient for there to be a creative class that can survive and thrive .

That being said, there is a lot of very fine music being made by people who are putting heart and soul into its creation and there are still vast audiences of people who want to hear it.

The evolution from analog to non-linear digital recording was a massive change both in how recordings were created as well as in many ways, altering the very nature of performance.

The emergence of AI tools will have an equally if not more profound effect.

It is up to artists to use these things to facilitate and aid music creation, not automate and dehumanise it. That being said, there are whole genres of music that are being changed forever by this.

One thing I also try to stress is that music is not “content”. It’s something much better than that.

Is there anything you have coming up or have done recently that’s exciting?

I have just finished projects with a couple of wonderful LA-based artists. I’m also currently music supervising a documentary project about a legendary jazz and soul trumpet player named Marcus Belgrave. These music docs are so fun to work on as I get to put on a few different hats.

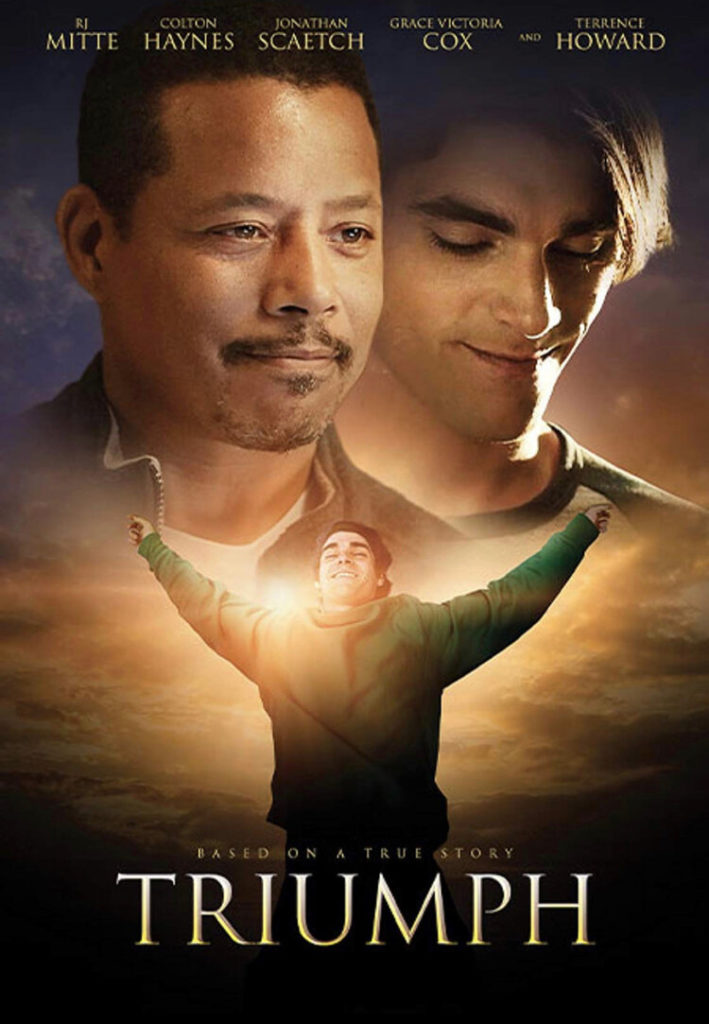

Last year I made a bit of history by creating the first NFT for a feature film score for my work on a movie called Triumph. Beyond all of the excitement of the collectible market, I’m very interested in the use of NFTs and blockchain registration for IP protection and rights management. It’s important for all of us independent creators out there. The Triumph NFT represents a marker on the timeline of adoption for those purposes.

Apart from the music and film world, I am partners in a company, AVA Inclusivity, which has developed and patented a software tool that provides digitally accessible navigation for people who are disabled to access web-based 3D environments such as virtual tours. I’m proud that we are getting ready to launch in Australia.

Find more information on Gregg Leonard here.