A musical analysis of Frusciante's first ventures into the solo sphere during a time of deep personal struggle

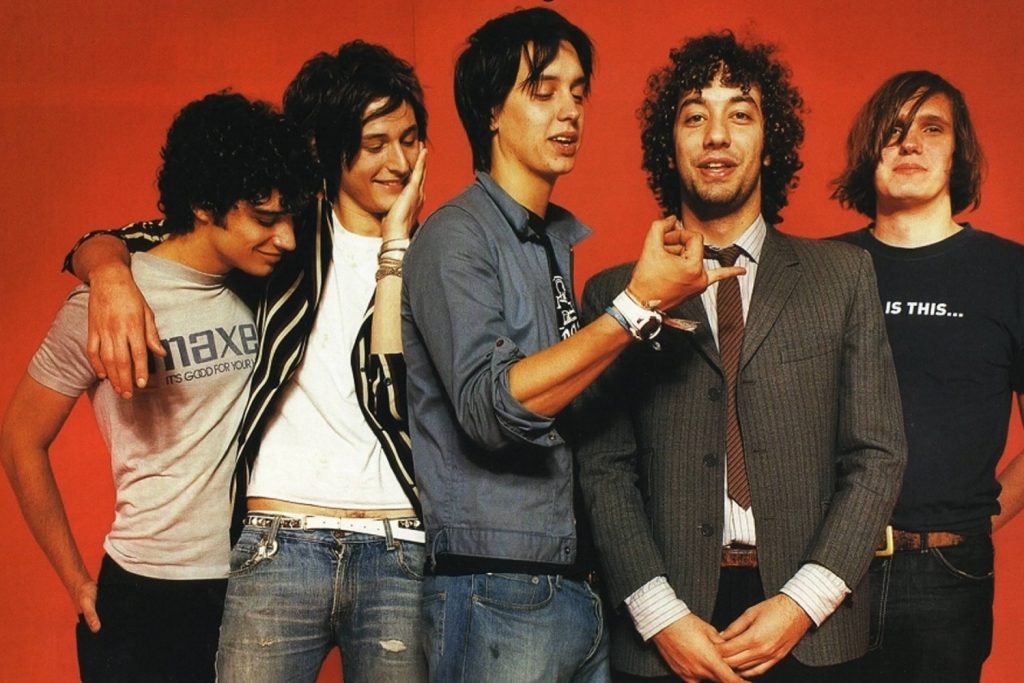

In 1992, John Frusciante, a 22-year-old guitarist from LA, stares into a rabid mass of nearly three thousand fans, halfway across the world at Omiya Sonic City Hall, Saitama, Japan. Every single one of them know his face, his name, but most importantly they know the way he sounds, note for note. As the crowd chants the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ name, Frusciante walks off stage, and doesn’t look back.

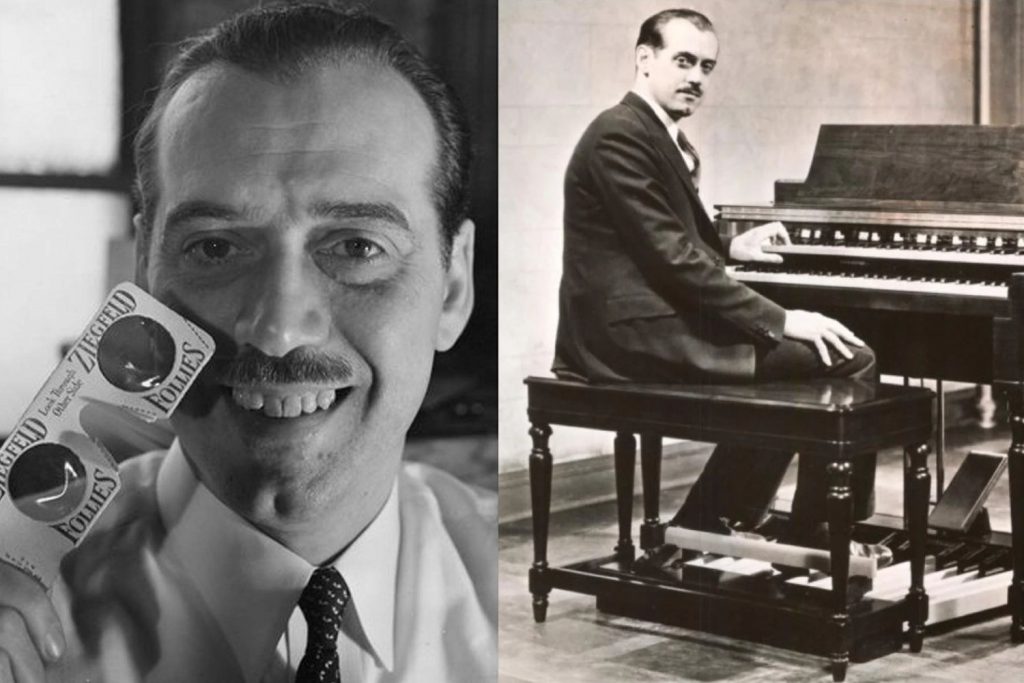

In lieu of global touring, Frusciante treated his body like a chemical punching bag; an aimless former rockstar with bottomless pockets and a crippling new taste for heroin. As described by Robert Wilosky for The Phoenix New Times in 1996, Frusciante’s upper teeth were replaced by “tiny slivers of off-white that peek through rotten gums” and lips “pale and dry, coated with spit so thick it looks like paste”.

Read up on all the latest features and columns here.

In 1994, the musical consequence of Frusciante’s lifestyle was released for judgement in his debut solo album, a double LP entitled Niandra LaDes…Usually Just a T-Shirt. Few could have predicted the fractured low-fi surrealism of his post-Chili Peppers solo trilogy, three records so bizarre that Frusciante tried keep one of them out of print.

The result was a kind of hysterical brilliance that acted as a score to Frusciante’s struggle with addiction, and created a musical trilogy well worth a closer look.

Niandra LaDes and Usually Just a T-Shirt

Niandra LaDes… resembles none of the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ hard-funk interpolations. The first disc is a collection of abstract acoustic songs recorded and produced in a splintered low-fi fashion, largely with a four-track recorder in a DIY fashion at home.

Much of it verges on the profoundly hideous, yet there is an undeniable perverted beauty to the record, erupting from a virtuosic drug-addled subconscious.

The album was predominantly recorded during the end of Frusciante’s first tenure with the Chili Peppers and directly afterwards, although the final mixing processes were reportedly heavily marred by his drug use. On Niandra LaDes… Frusciante plays like an undisciplined child, yet sings contrastingly explicit and often repulsive sexual lyrics.

Lyrically, Frusciante uses associational metaphors, full of deliberate malapropism. Everything in Frusciante’s world is reduced to a binary of pain and euphoria; be it sex, music, spirituality, or drugs. ‘My Smile is a Rifle’ is menacingly ambiguous, perhaps about music, perhaps something more sinister; ‘Your Pussy’s Glued to a Building on Fire’ oscillates between repulsive and heartfelt, an apology to his partner of the time, suffering through Frusciante’s behaviour.

One of the most glorious musical moments on the album is Frusciante’s cover of Bad Brains’ ‘Big Takeover’, one of the more cerebral exercises on the record. Frusciante had an unusual penchant for slowing punk songs down to draw out their melodic potential, and this was his surly psychedelic magnum opus.

The second disc of the album staggers even further left of centre, perhaps best described as a collection of atmospheric proto-electronica. The songs are misshapen, but are fashioned with great technical precision. ‘Untitled #3’ is a stunning paroxysm of poeticism, one of the few songs Frusciante has held onto live.

‘Untitled #6’ and ‘Untitled #7’ are a lone pair of Eddie Haze-like guitar showcases, but much of the rest of the record flows into a nightmarish drug limbo, voices fading in and out, acoustic guitar twinkling.

Smile From The Streets You Hold

Smile From The Streets You Hold is a vortex of chaos, a gasping subconscious with the last shreds of brilliance hurled about.

The material on Smile spans from 1988-96. Frusciante cobbled together the 17-track record to scrape up funds for drug money, and now feels too uncomfortable for it to exist in a public space, leaving it out of print. Large sections of the album are unlistenable, consisting of Frusciante’s voice screeching incomprehensible epithets as if they were scrawled on the wall of his drug den.

‘Enter a Uh’ opens the record with an infected cough, quickly filtering out any listeners uncommitted to Frusciante’s shattered psyche. A warbling shriek is accompanied by a fuzzed up guitar for eight whole minutes, while its lyrics are bonafide gibberish in sections.

Trying to describe the record with anything other than emotive descriptors feels redundant. Frusciante, once revered for his sublime technicality, now made impulsive and scrappy music. ‘A Fall Thru the Ground’ is a jarring and heartbreaking inclusion, recorded in 1988, the earliest of Frusciante’s solo work ever published and a slip of coherence from a naive 18-year-old Frusciante.

To Record Only Water For Ten Days

To Record Only Water for Ten Days was a personal and musical purification. The scuzz hiding Frusciante’s nimble fingers had been expunged through a reincarnated Red Hot Chili Peppers returning to success with Californication in 1999.

The title refers to the detoxification process, as if the body was a tape recorder, documenting only what is necessary.

From the first song, ‘Going Inside’, it’s clear Frusciante has undergone a panoramic rebirth. Using a simple programmed drum beat and howling in pitch perfect falsetto, he presses a complete reset on the lo-fi muck of the last eight years of his life.

Programmed drums form an interesting counterpoint to much of Frusciante’s guitar on this record; a deliberately simplified accompaniment focusing attention on the deft guitar. ‘Murderers’ is a taut and succinct instrumental encapsulating this sound.

What began as the documentation of a crumbling subconscious, vomited out through fumbling acoustic guitar on an eight-track, is now highly cerebral and conceptual, drawing on Frusciante’s love and vast hidden knowledge of self-programmed electro-rock. Frusciante’s falsetto features heavily as an endlessly malleable instrument as tracks like ‘Wind Up Space’ intertwine it with oscillating electronica.

The record’s opaque lyrical musings are a contemplative seal on the period of addiction, invoking the Hindu concept of true self, the atman, to challenge those who write off Frusciante’s infamous addiction as self-destruction. The crazed, dadaistic word collage of his ‘90s work would never return again, and though Frusciante was infinitely healthier, there is definitely a case to be made it was his literary peak.

What To Record did prove was define Frusciante’s endless aural creativity; his commitment to inventive sound design and creating angular instrumentals that don’t appear through traditional compositional veins. The record is the blueprint of the rest of John Frusciante’s dizzyingly prolific solo career, but it’s also the death of the ghostly void of his 20s. What was hollow had become full again.

Check out his full discography here to see the exponential improvement from his first releases.