How a classical composer became Melbourne's first true rock star

It’s well known that Australians are quite the inventive bunch. We’ve got the Hills Hoist, bionic ear, and wifi, among countless other innovations that have helped make the world a better place. We even have the goon sack to our name.

However, it’s often forgotten that one Australian was also responsible for laying the blueprint for synthesisers are we know them today: the eccentric composer Percy Grainger.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

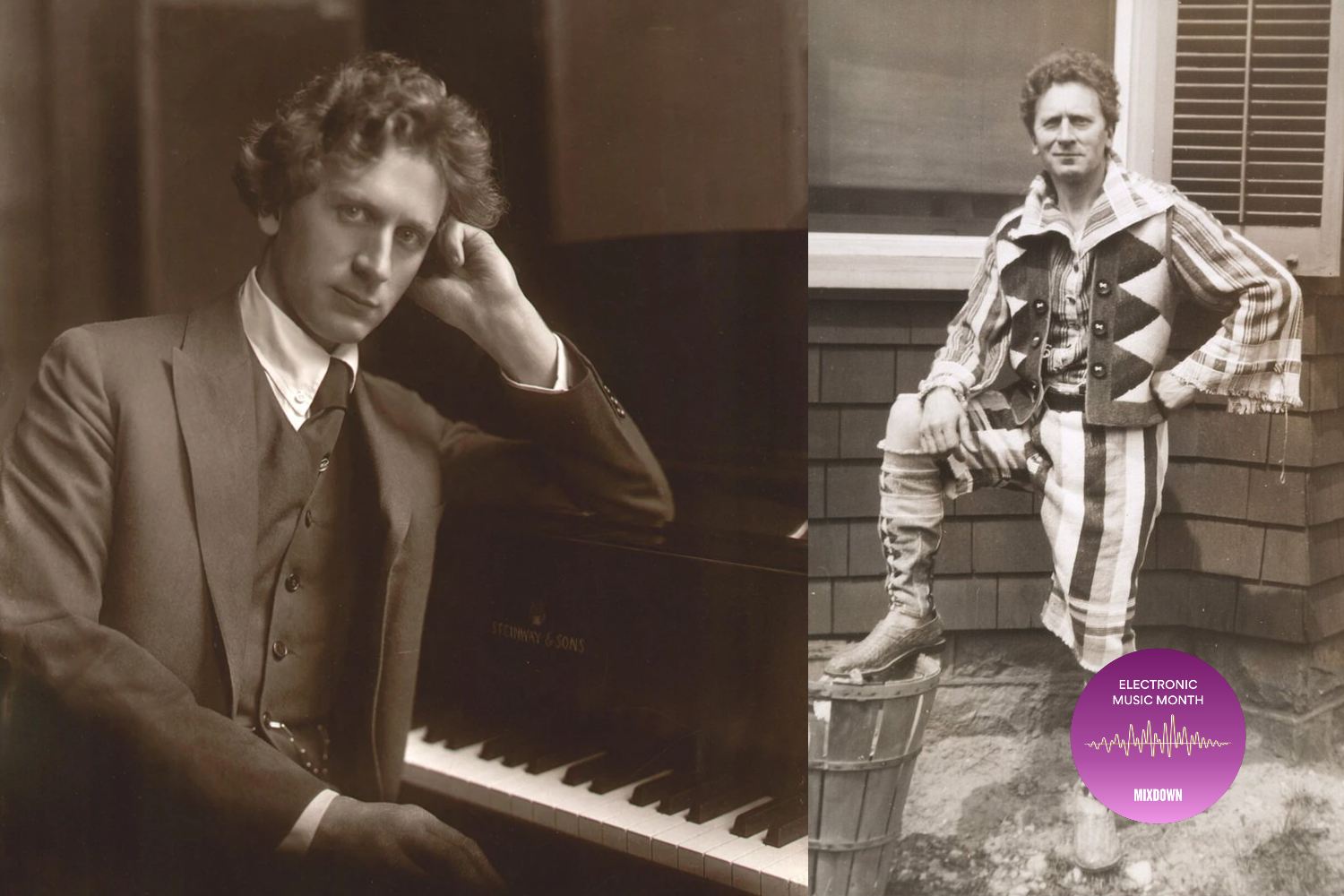

Born in 1882 in the Melbourne suburb of Brighton, Grainger was a prodigy behind the piano even as a child. He composed his first score in 1893 as a birthday gift to his mother, and was performing recitals at the Exhibition Building and Melbourne Town Hall to packed crowds at the tender age of 13. Soon after, Grainger made the move to Frankfurt to study at the prestigious Dr. Hoch’s Conservatorium, where he honed his composition chops, became an expert in counterpoint, and spent a lot of time drawing and painting.

Upon graduating from Dr. Hoch’s, Grainger moved to London and embraced the life of a touring musician, enjoying the glitz and glamour of dazzling aristocratic Europe with his lightning fast ability on the piano. However, unlike most of today’s rock stars, Grainger lived with his mother from 1900 until he moved to New York in 1914, with the prodigal composer being rumoured to have been harbouring an incredibly peculiar and borderline incestuous relationship with her.

As you’re about to find out, he’s a bit of an odd dude.

By the time Grainger had relocated to America, he was already a celebrity in his own right with scores of his works being sold all around the world. After briefly serving in World War I as a US Army bandsman, Grainger solidified his musical legacy with the 1919 composition ‘Country Gardens’, considered by classical music lovers as one of the best pieces of its era. Grainger went on to spend the 1920s churning out compositions and touring at an exorbitant rate, with concertgoers noting his increasing erratic onstage behaviour as the decade progressed.

In 1934, Grainger returned home to Melbourne and, in partnership with the University of Melbourne, founded the Grainger Museum at the institution’s inner-city campus. Grainger used the museum as a vessel to educate the Australian public about music, with some scholars citing his emphasis upon a universalist view of music and interest in cultures around the world.

Grainger was also known for recording folk music from indigenous cultures around the world with a phonograph, and loudly voiced his view for a nationwide embrace of the arts, proclaiming that “as a democratic Australian, I long to see everyone somewhat of a musician, not a world divided between undeveloped amateurs and overdeveloped musical prigs”.

However, Grainger certainly wasn’t a man without flaws. In his teachings at his museum, he often asserted his controversial views that the contributions of Nordic composers were superior to those of certified geniuses such as Beethoven and Mozart, with many of his rants on the topic implying an underlying racial prejudice that you definitely wouldn’t get away with in the modern world.

Grainger even took to designing his own clothes in this period, and although he did invent a precursor to the modern sports bra, his bizarre patchwork designs were largely ridiculed. When Grainger did wear his own clothes in public, he was often mistaken for being homeless: apparently Percy and Kanye West share a lot in common. Grainger was also notorious for being uncomfortably open about his sexual interests, and even left a cache full of whips, chains, lewd photographs and other kinky artifacts for university scholars to discover after his death. Like I said: odd dude.

It was around this time in 1937 that Grainger dedicated his work to the concept of free music; an idea he claims to have first materialised in 1892. Ever an advocate for the avant-garde, Grainger was fed up with traditional notions of musical theory, and believed that following conventions such as harmony and rhythm was “absurd goose-stepping” that musicians shouldn’t be forced to follow.

To pursue his idea of free music, Grainger began composing works for the theremin and solovox, and even invented his own variation on the theremin in order to totally defy principles of pitch, timbre, and performance capabilities. Throughout his experiments, Grainger attained a wealth of knowledge in the field of electronic music, creating complex automotive music machines and even achieving an early form of portamento as we know it today.

One of Grainger’s most bamboozling inventions, however, was a machine affectionately dubbed the Kangaroo Pouch: a device which controlled the pitch, volume, and timbre of eight seperate electronic oscillators. At a fundamental level, the Kangaroo Pouch was essentially one of the world’s first synthesisers. It utilised an array of rolls, mechanical arms, and cardboard contours shaped like a waveform to control the various aspects of each oscillator, which Grainger said would enable the user to “play the gliding tones and irregular (beatless) rhythms of free music.”

While incredibly primitive by modern standards, the Kangaroo Pouch was a triumph in Grainger’s quest against traditional music, particularly the way in which he envisioned the role of an oscillator to modulate sound. And although the Kangaroo Pouch may simply sound like an annoying air-raid siren, some would argue that its eerie gliding tones predated the invention of the monophonic synthesiser by several years.

Grainger also created a number of other instruments to compose free music, including a folding harmonium, the reed box tone tool, the eye tone tool and the Butterfly Piano, which was tuned in sixths to emulate those gliding tones he sought to achieve. Most of these contraptions have been saved or recreated in some form, and can be seen and even played at the Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne.

Unfortunately, Grainger passed away from cancer in 1961, and never lived to see his concept for free music materialised later in that decade with the release of Moog’s voltage controlled modular synthesiser. Nevertheless, Grainger’s creations have continued to captivate the music world long after his death, and his uncanny musical talent (and unconventional views and tendencies) prove that Grainger, by all means, was Australia’s very own first rock star.

Check out the Grainger Museum to learn more about this oddball of Aussie music.