The story of sampling is long and complicated.

From the early tape-splicing experiments of French musique concrète artists in the 1940s through to the plunderphonic wizardry of albums like Paul’s Boutique and Since I Left You, sampling has become known as the most contentious compositional method in musical history, seemingly never failing to spark an endless chain of controversies in its wake.

Although it tends to be most associated with international movements such as hip-hop or house, its practice as we know it today can actually be traced back to surprisingly local origins, with two young Australian music enthusiasts joining forces to create a device that’d flip music on its head when unveiled to the world in 1979: the Fairlight CMI.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

Considering Australia’s convict past, it really should come to no surprise that sampling was pioneered down under. The story of this fabled instrument kicks off in the early ‘70s with a young electronic music enthusiast named Kim Ryrie, who stumbled upon the idea of creating a DIY analogue synthesiser for Electronics Today International, a magazine ran by his family at the time.

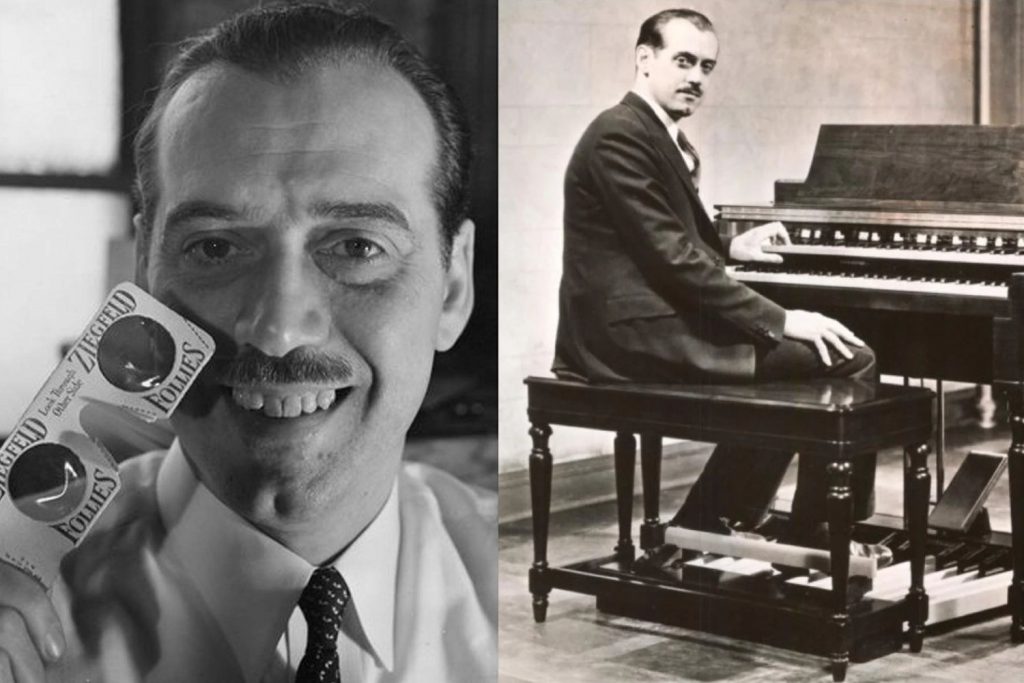

Initially dismayed by the limitations of analogue technology in the mid ‘70s, Ryrie got in touch with his former classmate and fellow electronics enthusiast Peter Vogel and pitched him an idea that was almost too bold to even comprehend back then – the prospect of creating the world’s first digital synthesiser. Basing their designs around the recently invented micro-processor, Vogel and Ryrie officially took their concept to the next level in December 1975, when the pair founded Fairlight in the basement of Ryrie’s Sydney home and began toiling away at their soon-to-be-revolutionary concept.

After the first six months of their work failed to garner any results, Vogel and Ryrie would later find out about the work of Tony Furse, a Motorola consultant who had designed a digital synthesiser in partnership with the Canberra School of Electronic Music. Intrigued by Furse’s decision to use two 8-bit microprocessors in parallel to create its digital sounds, the two young innovators licensed the design and integrated into their own work, emerging over a year later with a prototype that they called the QASAR M8.

While this synth did boast some features that’d make their way across to the CMI, such as the light pen and distinctive graphic interface, the QASAR was a ridiculously bulky unit that possessed a rather indistinctive and unpleasant sound. Despite being a big moment for the company, Vogel and Ryrie would subsequently refer to the QASAR as ‘research design’, and went back to the drawing board on their quest to create the ultimate digital synthesiser.

It was around this time that Vogel, in an attempt to understand the harmonic qualities of acoustic sounds, recorded a snippet of audio from a piano composition and discovered that the audio sounded much more realistic than a synthesiser when played back at different pitches.Compelled by his findings, Vogel coined the practice as ‘sampling’, and he and Ryrie went about modifying their design by adding in a QWERTY keyboard and a bulky box to house the sophisticated processing hardware that powered the unit, creating what became known as the first generation of the CMI.

Despite its rudimentary interface, scant sampling rate of 24 kHz and a maximum sample time of a single second, Vogel and Ryrie’s invention wowed Australian musicians and distributors when it was debuted in its earliest form in 1979. While the sound quality of the CMI wasn’t fantastic by any means, Vogel, perhaps by sheer intuition, felt that the unique timbre of the instrument would be a hit with artists, and that it’d be the freedom of the unit, not the overall quality of sound, that would define its creative potential.

Spurred on by the positive reaction to the device, Vogel took off to the UK in hopes of securing interest in the cutting-edge instrument, marketing the product to a number of science publications and managing to terrify the Musician’s Union with its sampling power before landing a chance appointment with Peter Gabriel. Stunned by the potential of the machine, Gabriel would be the first artist to employ the device on his self-titled third record, and would mint Syco Systems with his associate Stephen Paine in order to distribute the device at an eye-watering sum of 12,000 Pounds.

After the first CMI in Britain was purchased by an eager John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin fame, a number of prominent UK artists such as Rick Wright, Alan Parsons and Duran Duran’s Nick Taylor quickly followed suit and purchased their own, realising the unique appeal of the CMI and its grandiose potential as an ‘orchestra-in-a-box.’ Kate Bush was also another early adoptee of the CMI, famously employing the sampler to create the splintering broken glass sample that slices through the mix of her 1980 hit ‘Babooshka’.

Soon after, the CMI made its way across the Atlantic and into the hands of artists like Joni Mitchell, Todd Rundgren and Stevie Wonder, who would take the Fairlight CMI out on the road while touring Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants. Jazz-funk pioneer Herbie Hancock would also manage to get his hands on an original CMI, and even took to Sesame Street to demonstrate its real-time sampling functionality in front of a bunch of fascinated kids, possibly making for one of the most wholesome product demonstrations of all time.

As groundbreaking as it was, the original Fairlight CMI certainly wasn’t without its flaws: for starters, the Music Composition Language, or MCL, used to program the player’s movements was incredibly convoluted and impractical, and made programming the CMI a chore for even the most technically adept of musicians.

Vogel would amend these issues with the launch of the CMI Series II in 1982, which in addition to improving the overall sound quality and adding in a revolutionary quantisation feature, introduced an innovative Page R interface, now recognised by many as one of the first true music sequencers of the digital age. By presenting the notes of a composition in a horizontal layout that ran from left to right and cycled from bar to bar, Vogel essentially laid the blueprint for the DAW as we know it today, and artists went absolutely gaga for it.

It was around this time where the CMI really began worming its way onto some of the biggest records of the era, with Tears For Fears and Frankie Goes To Hollywood using the CMI Series II on their respective 1983 smash hits ‘Shout’ and ‘Relax’. Both tracks can be heard utilising two of the CMI’s most famous preset patches: the distinctive breathy vocals of [ARR 1], and the soon-to-be ubiquitous [ORCH 5], an orchestra stab which sticks out like a sore thumb in a number of great hip-hop, techno and drum ’n bass records of the ‘80s and ‘90s.

On paper, it would seem that the Fairlight CMI was essentially a one-way ticket to obtaining chart success during this period. In 1985, Jan Hammer scored himself a Billboard #1 hit by using the CMI on his theme for Miami Vice, becoming the last instrumental track to top the Hot 100 until Bauer’s viral banger ‘Harlem Shake’ snagged a top spot in 2013.

Early adoptee Peter Gabriel famously employed a CMI to create many of the tones in his decade-defining track ‘Sledgehammer’ a year later, and Phil Collins even felt compelled to state on the liner notes of his 1985 LP No Jacket Required that “there is no Fairlight on this record” due to the instrument’s prevalence on the radio.

Vogel and Ryrie would continue to work on a number of updates to the CMI Series II and even added MIDI to the unit upon its launch, and would go on to release a CMI Series III in 1985. A significant overhaul to its predecessor, the Series III added a number of improvements to the functionality of the unit, and added then-viable features such as CD quality sampling, a superior graphic display and a whopping 14MB of RAM – at a staggering cost of 60,000 pounds.

1985 also saw Fairlight introduce a number of other innovative products such as the pitch-to-MIDI-converting Voice Tracker and the CVI (Computer Video Instrument), a low-cost graphics, effects and paint processor that helped take digital animation to the masses.

However, Fairlight’s golden goose wouldn’t remain as a frontrunner within many music studios for much longer. sales soon began slumping due to the arrival of competing products such as the Akai S900 and Atari ST, which delivered hands-on MIDI sequencing and sampling at a much lower cost than Fairlight. To top it off, Ryrie and Vogel’s lack of business experience resulted in a number of costly mistakes and run-ins with venture capitalists in the US, and when the stock market crashed in October 1987, it looked like it was all over for Fairlight.

Against all odds, Vogel and Ryrie dipped into their own pockets for funding and managed to prolong Fairlight from folding and, with the financial backing of Australian distributors Amber Technology, relaunched as Fairlight ESP in 1989, with Vogel departing the company soon after to pursue work as a freelance contractor. With their sights set on the rapidly expanding post-production market, Fairlight ESP would continue to release a number of products into the ‘90s, including the MXF hard disk recorder/editor, which would be a common sight in post-production and broadcast studios throughout the decade.

Even though the technological innovations of the Fairlight CMI have since been eclipsed in the four decades since its emergence, there’s no denying the astonishing legacy that the device has left in its wake. Given the outrageous price-tag attached to most units, the CMI certainly didn’t democratise music-making in the same vein as trailblazing devices like the Akai MPC, Ensoniq ASR-10 or Korg Triton, but it’d be a huge oversight to say that it wasn’t an influence in the development of these units. It’s even possible to uphold the view that genres like hip-hop, house and techno would’ve evolved at a much slower rate without the introduction of the CMI.

And while it might sound basic and, dare I say, cheesy by today’s standards, there’s still plenty of artists that make use of the CMI’s sounds on a day-to-day basis, with a version of the instrument being made available as an iOS app by Vogel in 2011 and later as a virtual instrument included in Arturia’s acclaimed V software suite.

Above all, however, the introduction of the Fairlight CMI marked a symbolic changing of the guard for music. In an instant, being a musician was no longer defined by playing an instrument: even the most musically inept computer programmer could harness the power of the CMI to concoct sounds no regular instrumentalist could have ever dreamed of.

Fast-forward to 2020, and this ethos couldn’t be any truer; nowadays, a 16 year old producer with nothing but a laptop and a cracked DAW has just as much of a chance as scoring a Billboard Hot 100 hit as any major artist with multi-million dollar recording facilities and classically trained session players at their disposal. So, the next time you go on a long-winded rant about sampling ruining music, remember: none of this would have ever happened if it weren’t for two young Aussies back in the ‘70s.

Read more about the Fairlight CMI here.