Queer disco in the '70s was without a doubt a significant stepping stone in the journey of LGBTQI liberation

Throughout history, music’s significance has morphed contextually alongside cultural shifts, such as hip-hop giving a voice to black communities during the ’90s in Brooklyn, and rock ‘n’ roll during the sexual revolution in the 1960s. In these instances, music was a voice of power against an authority. It was significant as a cultural unifier, a social glue for the movements of the marginalised.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

We’ve decided to turn the clock back half a century. We wanted to take a look at a genre that grew alongside issues of social politics, gender identity, and popular music development, shaped by some popular and obscure artists. The queer disco scene of the 1970s was, without a doubt, a significant stepping stone in the journey of LGBTQI liberation.

It was a time that oversaw the maturing of the musical genre that not only formed a subculture in the urban nightlife scene in the USA – it provided a universal language of self expression and connection on the dance floor.

A turning tide

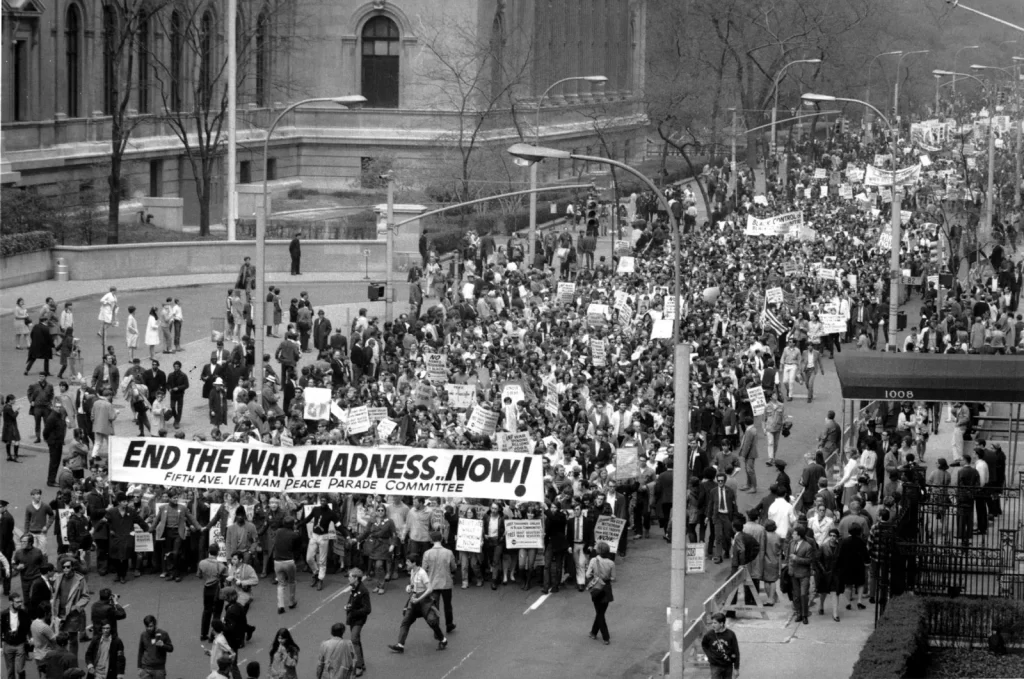

During the 1970s, popular music reflected a fun, free-spirited youth culture that questioned the government during and post-Vietnam War. Youth culture was heavily influenced by dance culture, and the popular music of the time included elements of glam, soft rock, punk and – especially – disco. Think Abba, The Village People, Queen, Elton John, The Bee Gees.

The Beatles broke up in 1970, and seeing as they were the original pop-influencers, it left a gap in the pop music market. This gap gave permission to other artists to go into new territories and explore different paths, which is one of the big reasons why genres such as disco developed so much.

In the 1970s popular music was televised more than ever before, and this influenced youth culture and an entire generation of baby boomers. The after-effect of WWII mass-production made leisure spending easier for Westerners from middle and lower classes. TVs, radios, and record players were more accessible and more affordable. This shaped how music and pop culture was globalised thereafter. For the first time, people experienced an upbringing in a time of peace, prosperity, and leisure spending.

For boomers it was a vastly different upbringing to that of their conservative parents, who experienced two world wars, the Great Depression, and a lower standard of living. This kind of global shift in lifestyles and attitudes framed the Vietnam War as senseless and violent. It cast a shadow on young people who were generally more interested in the notions of peace, self-discovery, and fun.

It was a defiance against the rigid values of their parents and the conservatism of the government. It’s therefore no surprise that the sexual revolution came about in the ’60s and ’70s – it’s also no surprise that ’70s disco had a similarly far-reaching effect. Disco’s global popularity helped to elevate its status as a subcultural shift for queer communities. In turn, this gave global visibility to LGBTQI rights and the Gay Liberation front.

Disco’s cultural significance and influence on queer communities

The 1970s saw a new self-awareness in the LGBTQI community that created a celebratory self-image. Disco culture was the seat of this.

As disco became more popular, LGBTQI communities started to experience politicisation alongside anti-Vietnam War movements. The air of self-expression in leftist political activity had a ripple effect through queer communities in the USA in the 1970s. Organisations such as Committee for Homosexual Freedom (CHF) and Vanguard formed in San Fransisco. They provided spaces to protest war in an atmosphere that encouraged non-conformity and self-identity. This was something that rang true with an entire anti-war youth generation and people that identified as queer.

This atmosphere of openness fed into the self-expression associated with nightlife. It inspired people to be themselves and dance in the arms of whoever they wanted. On the dance floor, it meant that queer individuals had an outlet to be themselves. Instead of being quarantined from the rest of society, disco clubs opened up a space where they felt safe to express their identity in a more radical and solidified way. What followed was a string of legal and illegal gay disco clubs across the USA.

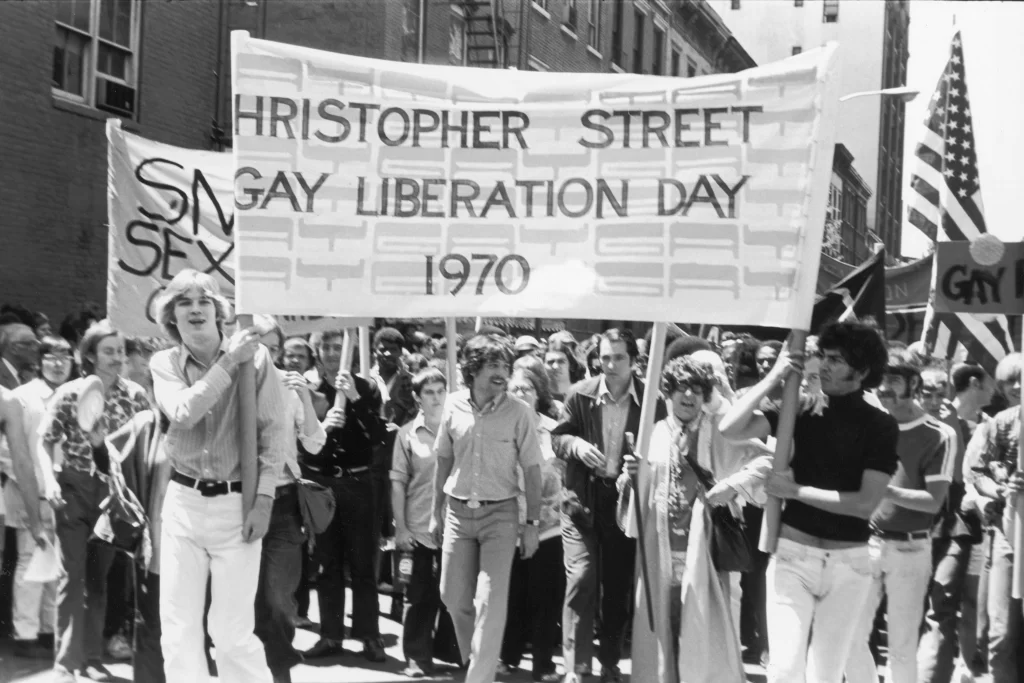

The Stonewall Inn in NYC was a precursor to these clubs, and was the site of a key event that shaped the future for LGBTQI rights and gay liberation. Between June 28 and July 1, 1969, the Stonewall Riots took place in Christopher St, Greenwich Village. It started with a routine raid by the police. The Stonewall had no liquor license as it was run by the mob, so the police came with the intention to collect bribe money. However, tensions escalated as the police threw some homophobic insults and made some arrests. The patrons of the Stonewall formed a crowd outside in the street, which started to grow in numbers with passerbys, making it difficult for police and venue staff to leave the area.

What ensued was a three day protest, which turned the riot into a movement. Many members of the protest were part of the core formation of the Gay Liberation front, creating the world’s first gay community centre. The basis for Pride marches came about by an annual gathering at Christopher St every June 28, marking the anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

Following the Stonewall riots, society was still predominantly homophobic. Even so, visibility of LGBTQI communities increased in the radar of politics and media. Lesbians and gay men started to be elected to public offices and civil rights protections for gay people were adopted in many cities. Sodomy laws were repealed in some US states. Some presidential candidates were more vocal about supporting gay rights, and local gay community centres received federal grants. This was aided by the groups like the National Gay Task Force, who hired professional lobbyists to influence media coverage and legislation regarding gay people and their rights.

This forward approach was one of the key reasons that queer individuals were encouraged to be seen and heard by society – image-consciousness, accommodation, and assimilation became pillars of the Gay Liberation movement. It was no longer about remaining invisible to avoid judgment. It was about gay rights becoming human rights, a normality that should be privileged to any citizen.

Disco was the soundtrack to this, being an inviting and open means for queer communities to go and connect. As disco became more mainstream, clubs catering for heterosexual people also began to pop up across the US, which further influenced youth culture and the growing popularity of gay clubs.

Audio technology’s influence

When you think about the audio technology of the 1970s, it helps to understand why disco sounded as such, and why it was received by the masses like so. Disco was groundbreaking, slick, expansive, funky, and reached into the hearts of an entire youth generation. How could it do that?

Maybe it was the fact that the eight-tape multitrack jumped to 24 tracks, expanding the magnitude and versatility of recorded music. This marks the 7’0s as a decade as a pioneering phase for popular music and the youth culture that listened to it. Household name microphones such as the Electrovoice RE20 and the AKG D-124 and D-90 ensured high quality audio, capturing diverse and experimental music instrumentation in popular genres.

In addition to better quality gear was the fact that there were now electronic musical elements to the sonic palate. Leading up to the ’70s, the Moog synth was used on Abbey Road (1969) as well as the first electronic album Switched-on-Bach (1968) by Wendy Carlos, which sold a million copies by the mid-’70s. Kraftwerk started to use vocoders and an EMS synth, and the Electric Light Orchestra further popularised synth-based music to lay the foundations for future electronic music. The characteristics of ’70s disco infused these electronic elements with expansive instrumental sections.

Wendy Carlos

Wendy Carlos, as per mentioned, was an artist that largely contributed to the popularisation of electronic music with her music, which garnered her unexpected commercial success following its release. It landed her three Grammy awards and a contract to make the film score for Stanley Kubrik’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). However, Carlos is a driving factor behind the scenes of the queer disco movement of the ’70s in that her advocating of synthesisers helped expand the disco genre, hence giving it the extra sonic driving force it needed.

Carlos was also transgender, having started hormone replacement treatments in 1968 and undergoing sex reassignment in 1972, which she was able to fund after the commercial success of Switched-On-Bach. For marketing reasons, she released two more albums as Walter Carlos – Switched-On-Bach II (1973) and By Request (1975) – but she became open about her transgender status and her struggles with self-identity in a 1979 Playboy interview. Her acclaim as a successful experimental electronic artist provided a platform for her to inspire solidarity in others struggling with their own gender identity at the time.

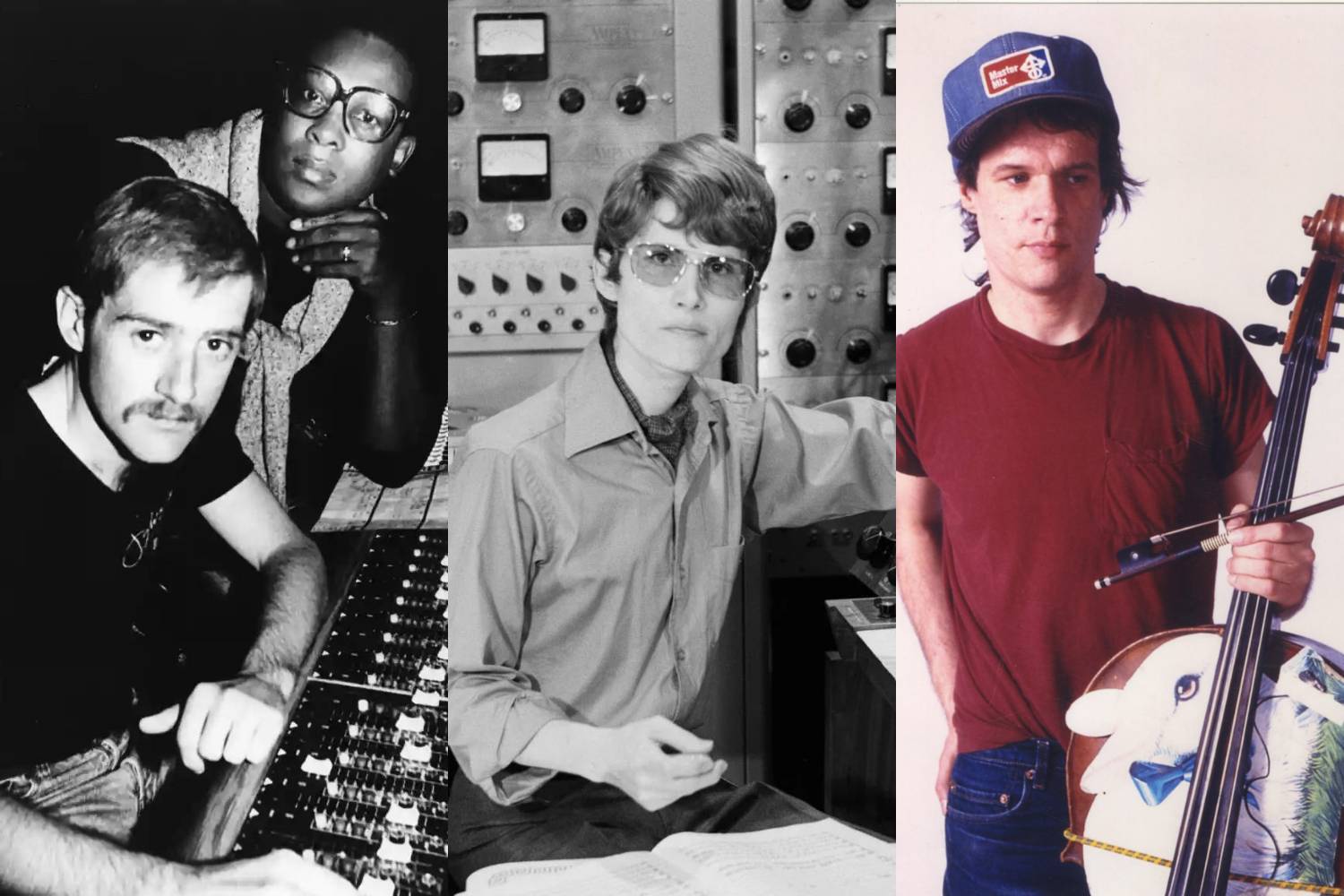

Patrick Cowley

Patrick Cowley was also a predominant artist that explored new territories in disco with electronic instrumentation. He was the creator of hi-NRG, an upbeat style of disco, and was widely regarded as one disco’s most important producers. While he gained more traction in the queer disco scene in the ’80s, he began to be influential and formed some key creative partnerships in the ’70s. In 1971 he studied synthesisers like ‘The Putney’ EMS VCS 3 at one of the USA’s first electronic music schools – the City College of San Francisco’s Electronic Music Lab. His experimenting on synths caught the attention of performance artist Jorge Socarras, whom Cowley finished a body of music with in 1977. The work was released posthumously in 2009 as an album, Catholic.

It was this unreleased work that disco/R&B artist Sylvester listened to in 1978, which spurred him to ask Cowley to join his band. The two collaborated on various hit tracks such as ‘You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)’ and ‘Dance (Disco Heat)’ from Sylvester’s album Step II (1978), and they further worked together on Sylvester’s 1979 album Stars. The collaborations with Sylvester provided a platform of musical status that Cowley used when releasing his own disco hits in 1981 such as ‘Menergy’, a distinct celebration of the gay club scene, and ‘Megatron Man’, which hit #1 and #2 on the Billboard Hot Dance Music/Club Play chart in 1981.

Cowley passed away from AIDS early at the age of 32, which may be one of the reasons why he never fully achieved mainstream commercial success. Nevertheless he’s known as a purveyor of electronic music in the disco scene.

Arthur Russell

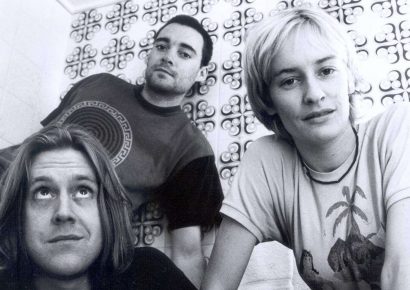

Another influential member of the disco genre was the cellist, composer, singer, and producer Arthur Russell who had a considerable role in the NYC disco and underground arts scene during the ’70s. He formed the disco groups Lola, Loose Joints, and Dinosaur L – which had several underground disco hits including ‘Kiss Me Again’ (1977). His musical influences had roots in country, disco, and avant-garde, with elements of contemporary experimental composition and Indian classical music – both of which he was trained in. He frequented dance clubs in NYC through the ’70s, which fed into his music making and attraction to the underground arts scene. Russell was a prodigious collaborator and producer, working with the likes of Steve Reich, Phillip Glass, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Gordon, David Byrne.

Though he’s known as an influencer in the ’70s NYC queer disco and avant-garde scenes, Russell released his limited catalogue of solo albums in the 80s; 24→24 Music (1982, as Dinosaur L), Tower of Meaning (1983), and World of Echo (1986). He passed away from AIDS-related illnesses in 1992, though a series of reissues, compilations, and a bio-pic has posthumously raised his profile further than he ever knew in his lifetime.

When talking about disco, it’s not the first musical genre people bring up when talking about social and political change. However, disco is anchored in history as a soundtrack for a subculture that embraced self-expression and empowerment of the marginalised. The 1970s was an exciting and challenging time for LGBTQI liberation, and disco clubs planted the seeds for strength, visibility and solidarity in the face of homophobia.

Disco is also a winner on any contemporary party playlist when you wanna let loose. It just sounds too fun not to dance to. That’s a profound thing in itself. It’s got an infectious way of making people move, which ties in with its cultural significance. More proof that music is the great social enabler, binding people together from all backgrounds and corners of history.

So next time you listen to ‘Dancing Queen’, bite your lip and have a boogie. It’s powerful stuff. <3

Head here for more.