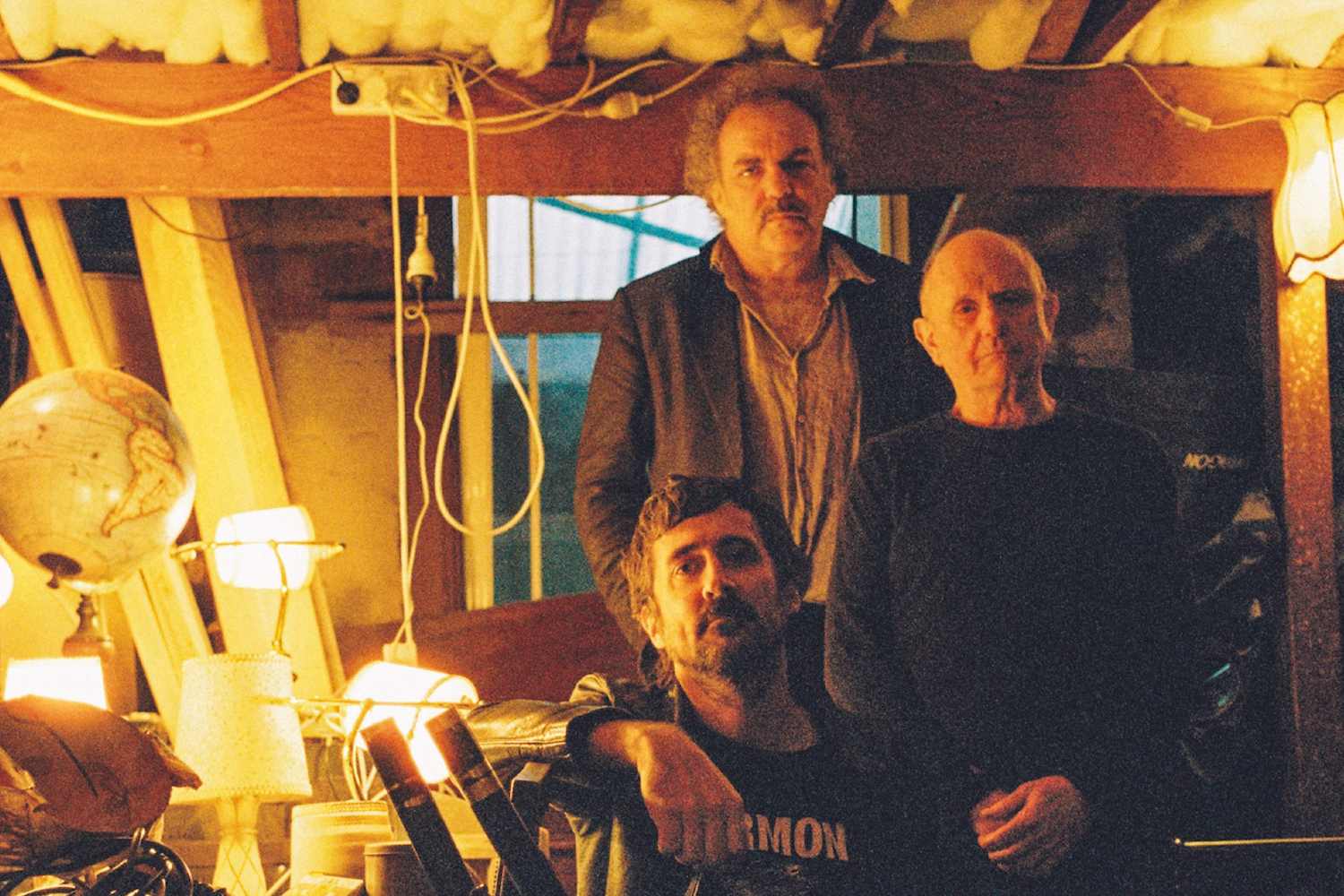

Gareth Liddiard, Chris Abrahams, and Jim White walk into a studio...

Mike Deslandes sits in the middle of his mixing room, surrounded by gear. Rain clouds are rolling in and the air is cool and still – but the room is warm from the power supplies in racks of EQs, preamps, and compressors to his right and the Toft console to this left. Big ADAM monitors sit between all that, ensuring everything is within arm’s reach of the listening position.

There’s a mix up on the console, the gear in a constant state of flux with the number of records passing through this room, and I’m weary of touching anything that might ruin the recall, a process still very much apart of Mike’s workflow – he’s decidedly analogue-minded and has been since he began recording.

Some of this room was moved out to Nagambie to record Springtime, the result of collaboration between Gareth Liddiard (Gaz) of Tropical Fuck Storm (TFS) and The Drones fame, Chris Abrahams (The Necks, The Whitlams), and Jim White (The Dirty Three). A supergroup of sorts, the experience became Mike very much experiencing Springtime as it was created, watching the trio build it from the ground up.

Read up on all the latest interviews here.

“I guess I was a part of the working team at that moment for those few years,” says Mike, referring to his time working on both the more recent TFS records and Springtime. “(Gaz) is an accomplished engineer in his own right, he just wanted to do his thing and not have to worry about that stuff. He wanted a proper engineer to get there, do the job, be on the job… and I do a lot of portable location recording so this was another one of those but in a transportable home.”

Nagambie is a small town that’s a little detour on the way to Bendigo, north of Melbourne’s CBD. It’s peaceful, full of flora and fauna, and isolated enough for a band to focus on making a record without distractions. Idyllic surroundings aside, the property also allowed Springtime to get loud if they needed to.

“[Gaz] saw me as someone who would work efficiently… it’s just how you solve the problem, and we’ll get it done,” states Mike, speaking to the importance of saying yes wherever possible to give the band whatever they need. The makeup of Springtime is an interesting one being three musicians vaguely associated with rock and just about all its surrounding genres, but made up of a “baby grand piano, full drum kit, with some, y’know – Jim’s always got a bit of different percussion”.

“It’s fully live… we had the full vocal P.A. going at the same time with vocal effects and loops, [Gaz] obviously had this guitar and guitar amp.

“Having done a bunch of these before… being out, doing location recording, you know to just be over prepared. So, I bought out a whole bunch of stuff.”

Mike’s focus shifts as he begins to discuss his role within a record – which changes from project to project. While sometimes musicians on a session need a push, a teacher, cheerleader or project manager – Springtime needed none of this.

“All of the songs are the recorded performances, vocals and everything,” Mike assures me.

He recalls thinking, “I’m gonna let them do their thing, and knowing them as players is like – players play, it’s a bit different to, ‘Hey we’ve got these structured songs and we’re gonna come in, tick off every little moment until it’s done’.

“The best thing about location recordings is [that] you’re forced to solve every problem and it’s only you that can do it, so get it done.”

Mike moves to discussing the problems he encountered while making Springtime, noting that the baby grand was set up with its top open, and half a metre away was a drum kit. Both of these are very dynamic instruments on the record, but another half metre away was Gaz, a foldback wedge, and a guitar amp blaring. “On the engineering side, it’s a nightmare really. It’s not great.”

But he made it work in the interest of giving the band everything they needed to make this record.

Mike had a control room set up about 30 metres away from the main live room, a mobile home on a block, connected via hired looms so he could monitor what was happening. Springtime is very dynamic, the performances informing the energy of the room, and the band needing to focus on each other’s playing rather than metering, signal flow, and monitoring.

“They play, so I learnt very quick that the tape just always rolls,” he says with a laugh. “I was there to document their recording, if that makes sense… my role within that was to document what they did, and then mix that.

“I wasn’t thinking anything sonically, I was thinking emotionally. For this to happen, I don’t need to distract them. They were gonna do what they were gonna do, and it was gonna be how it was meant to be.”

Mike understands his role within the machine, and in this case he was purely an engineer, allowing the chemistry of the band to push the record towards the finish line. “Sometimes in my job, I need to be leant on for advice, so I do need to be present. With Springtime, I didn’t need to be there at all. I just needed to be documenting it.

“I knew after set-up on day one that I was trusted by Chris and Jim, who I hadn’t worked with. They saw that I didn’t say no to anything and I was getting it done.”

“These are professional musicians… their life’s work is this. This is how they eat, and I knew that that was what I was walking into.”

The resulting recordings are Springtime which has done scattered tours throughout the country. When pressed on him being the right person to get this job done, Mike laughs, “I’m always an imposter. I was very grateful to be asked… just to be witness to that type of stuff. That level of work. To be a part of that was pretty damn cool.”