Taking you behind the production of one of Australia's most heavily-produced track of the time out of the nation's premier recording studio.

Over budget, brandished as “utterly rubbish” by the label, but ultimately successful thanks to some Molly Meldrum Magic.

When sessions began for ‘The Real Thing’ at 7pm in the summer of 1968/9 at Armstrong Studios in Melbourne, it was to be a conventional three minute track.

An Australian album then cost three to four thousand dollars (or almost 50 thousand in 2022 money) to make.

The bean counters at EMI Records assumed that it — and the B-side, the Hans Poulsen-penned ‘It’s Only A Matter Of Time’ – would ker-ching to no more than a few hundred dollars. When costs sailed past 10 thousand dollars (more than 120 thousand dollars today), EMI panicked, tried to seize the tapes and sacked its producer Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum.

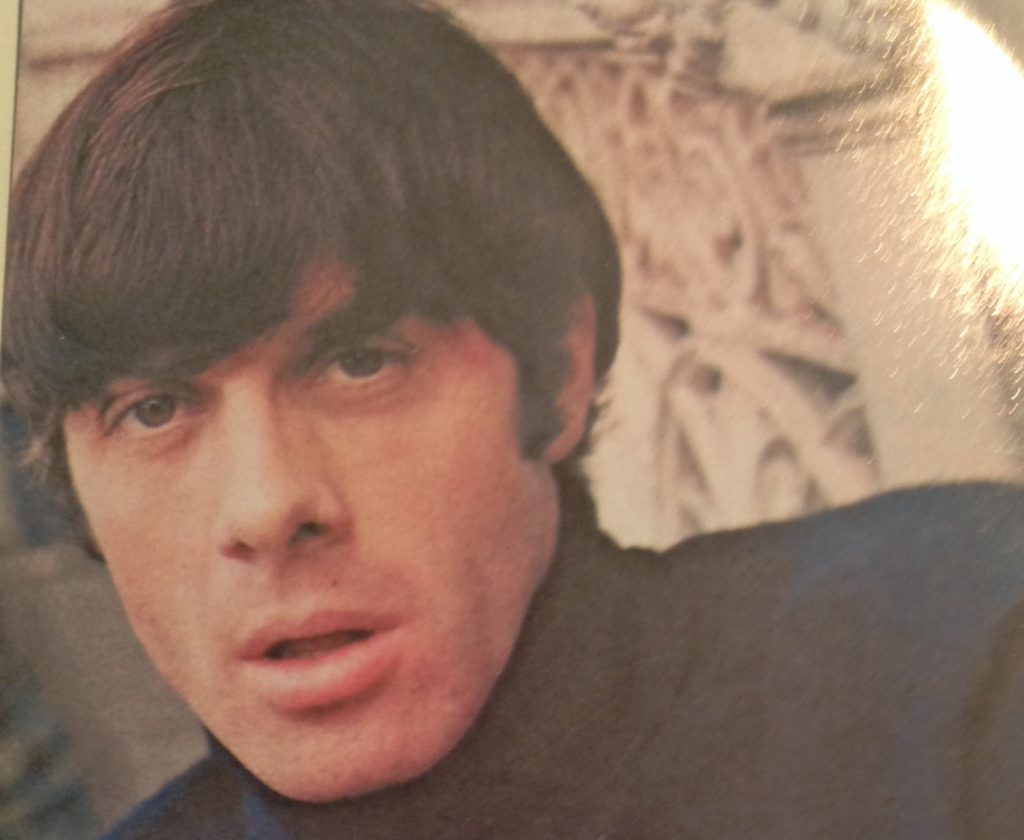

(Image via Mushroom)

(Image via Mushroom)

More than 50 years after the fact, it was inevitable it became a psychedelic Meldrumatic explosion, given the characters in the play.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

Russell Morris, the shy teen surfer who gave up studying accountancy for music, knew his debut solo single had to be left-of-centre if he was going to cut his jib in a field of male warblers like John Farham, Normie Rowe, and Ronnie Burns.

In agreement was his manager Meldrum, the 10-pound-a-week writer at Go-Set magazine, who was a dancer on the mime TV show Kommotion.

Meldrum had managed Morris when he was in the band Somebody’s Image and produced their minor hits ‘Hush’ and ‘Hide And Seek’, so the singer was well aware of Meldrum’s modus operandi in the recording studio.

“He’d get (Somebody’s Image) to play and play and play, for four hours,” Morris recalled. “The band would be exhausted. But Molly had a good ear. He’d be listening intently and suddenly jump up and say, ‘That’s the bit I want!’

“Or he’d say ‘I want it to sound like very white stars on a very cold night’.”

Before the ‘Real Thing’ sessions, Meldrum was in Swinging London as a junior producer at The Beatles’ company Apple.

“Coming from that atmosphere, I was ready for something ambitious when I came home,” he told Mixdown.

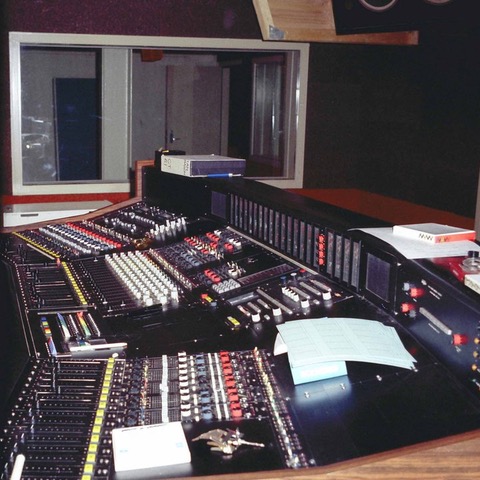

Armstrong Studios

The fact that the ‘The Real Thing’ was recorded at Armstrong Studios in South Melbourne was also an important element in the story.

Bill Armstrong had a creative atmosphere with engineers who could break the rules if need be. Armstrong built a disc cutting machine as an engineering student at Caulfield Tech. A jazz buff, he set up a machine in the veranda of the family home and taped jazz musicians so they could hear what they sounded like.

After stints as a recording engineer for two radio stations and building a studio in a church for W&G Records, he went out on his own in 1965.

Armstrong Studios was set up in a terrace house at 100 Albert Road, rent at 18 pounds a week. At the time making jingles was the more lucrative business, and Albert Road was chosen because that is where the ad agencies were.

Many Sydney studios were full of grey-suited fuddy-duddies. One installed a sensor to cut off that nasty rock if it exceeded the noise level!

But Armstrong Studios had a different culture, always with an exciting vibe as the likes of the Easybeats, John Farnham, Brian Cadd, and the Masters Apprentices cut their tracks.

It started with a mono tape by local company Rola, and then to a two-track, and then to a four-track.

In 1968, Armstrong took a punt on an eight-track by New York company Scully.

“They air-freighted it out to us by Friday, and by Monday we had it working,” he said. “We were the first studio to have an eight-track outside America. Not even Abbey Road in London had one.”

Armstrong worked to get creative engineers on his team. They included Roger Savage who started out as a junior at London’s Olympic Studios helping the Rolling Stones cut their early demos.

Armstrong then expandd his recording capabilities through Graeme Thirkell and his company Optro, who made 16-track machines that were technically better than the bigger brands. He built a 300-watt power amp that put out 240V and locked to 50 Hz, and in which he put in an oscillator which could vary its speed.

The studio eventually housed a 24-track and combined with the personnel, Armstrong Studios was the most state-of-the-art facility in Australia, putting Australian music on the map.

OO Mow Ma Mow Mow

Working on ‘The Real Thing’ was John L. Sayers, a New Zealand-born engineer, producer, and studio designer who joined in 1968.

On the first night of recording, Meldrum handed Sayers a three-inch tape with ‘Johnny Young demo’ scribbled on it, and asked him to run off a copy.

It was for the conservatorium-taught Zoot guitarist Roger Hicks, so he could go off to Studio B to come up with an acoustic intro. The intro channelled Hicks’ guitar hero Jose Feliciano. It would be the last bit to be included in the final product.

Young had reluctantly made the demo after Meldrum turned up late one night at his house with a tape recorder.

Earlier, in the green room of the Uptight TV show in the 0/10 (now Ten Network) studios in Nunawading, Young played some songs he’d written in London while staying with Barry Gibb.

He pitched ‘The Girl That I Love’ but Meldrum and Morris rejected it as being too conventional a ballad with which to launch a solo career. But when they overheard Young strumming ‘The Real Thing’, they zeroed in on that pronto.

Its nonsensical LSD-coded lines like, “There’s a meaning there, but the meaning there, doesn’t really mean a thing” was spun as an anti-corporate message inspired by Coca-Cola’s “real thing” ad blow-up in 1967. Young wrote it with a group, texturally similar to The Beatles’ ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ or ‘I Am The Walrus’.

Besides, he’d promised it to someone else.

That mattered little to Meldrum, who clinched the deal with the late night home visit.

Young: “I didn’t think it was right for a solo artist, but Molly was very adamant and kept pestering me. I give Molly 100 per cent credit for what he did producing ‘The Real Thing’.

“He can be an incredible bullshit artist, but in a studio he can be a genius. Considering the time and the technology back in 1969, what he achieved was incredible.”

At this point Young hadn’t finished all the lyrics, so he threw in the ‘”Oo mama-mow-mow, oo mama-mow-mow” promising to finish them off. Meldrum thought he’d substitute a guitar riff.

The track included The Groop’s Brian Cadd (organ, piano), Richard Wright (drums), and Don Mudie (bass). On the final of their practice run-through, The Groop were on fire and continued to jam on.

Sayers and Meldrum realised they were onto something good, and Meldrum signalled frantically from the control room for them to keep going.

The tape broke after 10 minutes.

Later while checking the tape for leakage, Sayers found Cadd’s piano was covered enough to feature it on its own. Hence it was used as a bridge before the rest of the band was brought in to the record’s climax.

There were backup vocals from The Groop’s singer Ronnie Charles, Danny Robinson (Wild Cherries), and The Chiffons (Maureen Elkner, Sue Brady, Judy Condon). The gifted Billy Green of Doug Parkinson’s In Focus (now known as Wil Greenstreet) contributed electric lead guitar and sitar.

To fill in the extended track, Meldrum went to the sound library and came up with, among other things, a World War II Hitler Youth choir singing ‘Die Jugend Marschiert (Youth on the March)’ which finished with a defiant “Seig Heil!” and an atomic explosion Sayers thought so marvellous he’d sneakily use it on later TV productions.

The Hitler-type speech came from Cadd holding a megaphone made of rolled-up paper reading the instructions on an Ampex tape box.

A ghostly second voice echoing Morris’ lead vocal added to the myth a ghost haunted Armstrong Studios and played with the faders. But it was just Meldrum’s vocal guide to Morris.

To get the new ‘phasing’ effect that Meldrum loved on the Small Faces’ ‘Itchicoo Park’, the mix was brought off the Scully eight-track onto the Ampex AG-440 in the control room.

“There was a similar AG-440 at Philips Studio four houses away, with cables running over the roofs of the houses,” according to Sayers.

“I sent the signal to both the AG-440s, and brought them back into the console next to each other at varied speed against one another.”

Sayers regarded the resulting ‘wooshing’ effect as unbeatable and better than digital versions.

Money talks

Meanwhile, Meldrum kept doing remix after remix over months, and costs escalated.

During an acrimonious phone call, EMI sacked him. Meldrum argued the tape was his. EMI fired back it was theirs as they were footing the bill. EMI despatched two Sydney execs that afternoon to Melbourne to seize the tapes.

A call was put to Armstrong to lock Meldrum out of the studio in case he tried another remix.

According to Morris, before the EMI dudes came, an anxious Meldrum dosed himself with brandy. When they arrived, he grabbed the master tape and scurried to the park across the road.

Morris and Sayers went looking for him, torches in hand, and found him huddled under a bush clinging on to the tape.

They took him back to the studio for a playback. As Molly expected, EMI hated it. The words “utter rubbish” were bandied around. They told him it would only be released in Melbourne, to cover at least some costs.

Undaunted, when the song was released in March 1969, Morris and Meldrum got into the singer’s old car and drove up the East Coast. They stopped at every radio station, played the program directors the track and asked if they would support it. Some put it straight on air.

Faced with such widespread media support, EMI was forced to release it nationally.

It went to #1 on the national charts by June and stayed there for six weeks, remaining in the Melbourne charts for six months.

In England Decca Records gave it no push. The small Diamond label issued it in America with Pt. 1 on side one and Pt. 2 on side two without advising Meldrum or Morris.

That destroyed its chances but after checking which radio stations were playing it, an angry Meldrum sent them the 6.20 minute version, which they picked up on, and ‘The Real Thing’ went to #1 in New York, Chicago, and Houston.

Already traumatised by his newfound fame, Morris refused to go on a promo tour of the US, which led to a falling-out with Meldrum.

“I can’t say that the last eight months have been happy days for either Russell or myself. There were times when we hated each other’s guts,” Meldrum said at the time.

Meldrum produced more chart toppers, but for free. Being employed at the ABC during the Countdown days, he could not accept royalties.

Sayers engineered and/or produced more hits, wrote a manual on acoustics and studio design and designed 14 of them.

They included Music Farm Studio in Byron Bay, the Beyond 2000 and Charles Sturt University facilities, Apocalypse Audio Post Studio, Hello Testing, Cloud Studios, Flying Fox Studios, and the Australia National University Music School Recording Studio in Canberra.

He died in September 2021.

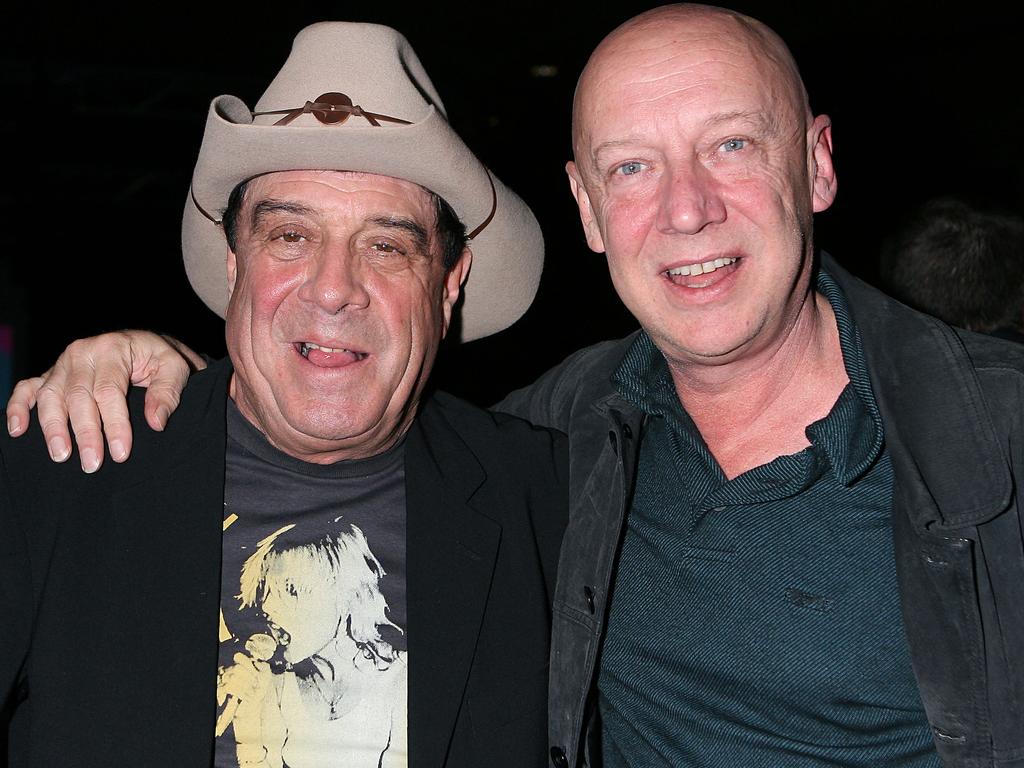

(Photo via Daily Telegraph)

For more technical analysis by Sayers on the making of ‘The Real Thing’, go to his interview with former Little River Band guitarist David Briggs here.