One of the most prolific bands of the past (almost!) three decades, Bright Eyes are back with their first record since 2020.

Their latest offering Five Dice, All Threes is a record full of singalong hooks, uncommon intensity and tenderness featuring notable guest appearances from Cat Power, The National’s Matt Berninger, and Alex Orange Drink. We sat down with frontman Bright Eyes Conor Oberst ahead of the release to chat about making the record, capturing the moments and the unsung magic of Mike Mogis.

Firstly, congratulations on the new Bright Eyes album, Five Dice, All Threes. I’ve been lucky enough to have listened to it a couple of times already and I just feel like there’s so much I can say about this record. It feels like a really exciting moment in time for Bright Eyes. How do you feel now that this record’s finished and is about to be shared with your fans?

I’m very excited. I think whenever we make a new record or whenever I release anything into the world, you don’t really have any idea what people are going to think of it. I mean, we just try to make things that we find interesting and cool.

I’ve always kind of likened it to, you know, you make this present and you wrap it up and you put a bow on top and you make it look as pretty as you can make it. And then you tie it to a balloon and then you throw it in the air and then it just sails away. You have no idea where it’s going to land or like who’s going to open it or who’s going to care about what’s inside of it. And so, yeah, it’s always a bit of a leap of faith I suppose.

You know, the hope is of course, that people relate and people get something out of it, but you never really know. We also have a joke – some of my friends and I that are songwriters – that when you make a record, all your management and your label and your publicist and everyone’s like, ‘Okay, this is going to be the one, it’s going to change your life, this is going to be it. This is the big one.’ And of course, it like never, never is.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

But that’s all right, I just feel lucky that we get to keep doing this after so many years as a band. I think longevity in itself is a success no matter what, like how many people buy the record, stream the record or care about it. But, I think this one came out cool. And I think as far as our music, it’s probably a little more immediate, or easy to get your head around.

Sometimes we do sort of weirder, longer, stranger things and this one feels more direct. They’re kind of like, I guess for lack of a better word, pop songs. There’s no 12 minute songs on it. So that’s a good start. [Laughs]

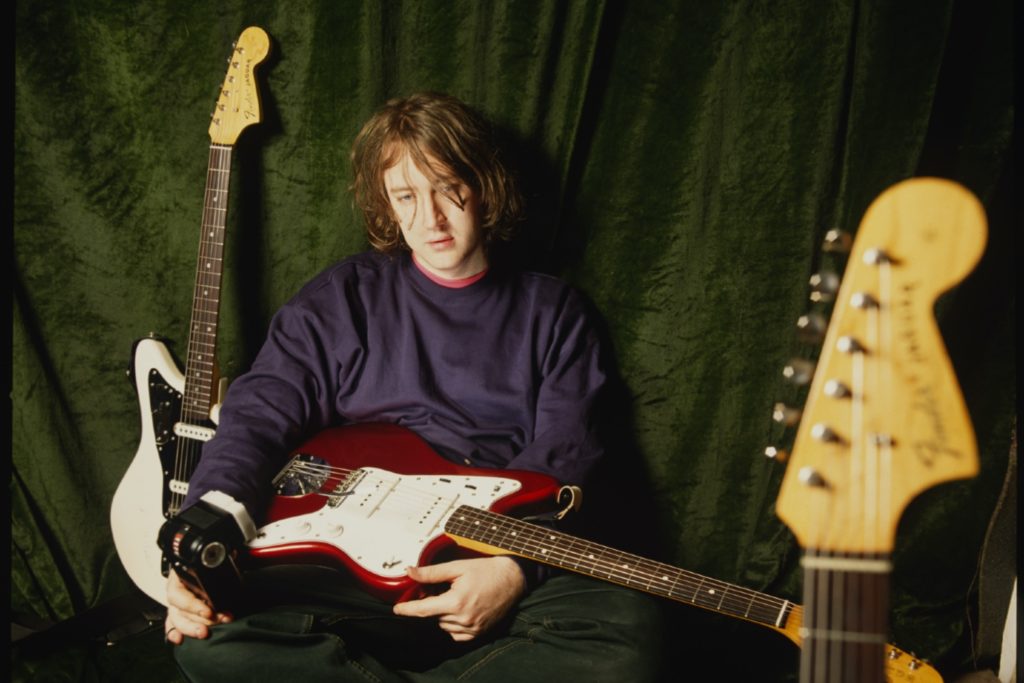

Conor Oberst

I really like that visual of wrapping up the album and sending it off like a present to the world, not knowing how they’re going to perceive it and how it’s sort of up to them at that point. You always hear artists talking about the broad spectrum of feelings they have when they release music, some people are just so nervous. It’s nice hearing you be like, ‘This is just going out there and what’s done is done.’

Yeah I think that my philosophy has always been that if you try to anticipate what your audience would like, or what people want to hear, you’re either going to end up just constantly repeating yourself, or you’re going to end up making something that’s not very good. So you have to kind of follow your instinct in the moment of creation, as you make the music. And yeah, then you hope for the best.

Some things just resonate more with some people… I feel like there are artists and friends of mine that are better at strategising how to get their music into people’s ears. I’ve never been good at that kind of thing. I find it sort of detrimental to the actual art that you’re trying to make. So it’s almost best not to think about that too much while you’re making it. And then, of course, you do the interviews and play the shows, take the pictures and try to promote the music.

To go back to what you were saying earlier about not really knowing how this comes across and how maybe it feels a bit more direct. As a record, I still feel like there is this real sense of familiarity that you get as a Bright Eyes listener. It feels like the band that you know and love, but there’s an adventurous quality to it. It feels like you’re still pushing the envelope there and trying to cover new ground as a band. I think that that’s something that your fans would be really into.

Yeah, I mean, thank you. And I hope so. I think in a weird way, to some degree it’s a throwback to some of the music that I grew up making and listening to. Like back in the 90s and stuff where it’s like, I don’t know what you want to call it, punk rock or indie rock or ‘pick your favourite sub genre.’

That was a lot of the music that I liked back then… like a band like Super Chunk or something. These kinds of punk-indie bands that it was like they were making a pop song but presenting it in a way that’s a little off-kilter. It’s not like pop in the sense of Top 40 radio, but you know it has catchy hooks and choruses and that type of stuff—which if you listen to some of our records, we don’t always do that.

Sometimes we tried to make the most sort of obtuse… just something that we almost were daring people not to like. I think this one feels more like, ‘Here you go, here’s some song I hope you can turn on and have fun listening to it.’ There’s not much more to it than that.

When you released your first single Bells and Whistles, I noticed that there was this real sense of enjoyment that came through in the way of ‘I’m just going to strum this guitar as hard as I can.’ There’s a really nice analog saturation that’s running throughout the whole record and it just sounds like a band that’s enjoying themselves, cutting loose, not really trying to play to any expectations.

Yeah I also kind of feel like, and this has been a long standing sort of situation with us, everything we do is somewhat a reaction to what we did before. And so, with the last record, Down in the Weeds, it’s a lot of big grandiose ideas and orchestras, with John Theodore playing drums and Flea playing bass.

I’m proud of that record too, but it was a lot more complex. And this one just feels like… I mean there’s still plenty of overdubs and plenty of studio magic that Mike Mogis provides and different effects and weird things happening in the recordings. But just as the songs and the presentation, we tried to keep it more on the live sound of a band playing.

In the studio we have a tendency to get carried away with some weird ideas, and then you’re just down the bizarro looking glass and making strange things happen.

… and before you know it it’s the end of the session you’re like, ‘What? Where were we?’[Laughs]

[Laughs] And that happens to us quite a bit. You have kind of a long day or late night, have all these ideas you think are great in the moment, and then you go back and try to listen to it and put it together the next day and we’re like ‘wow, we’re just psychopaths. We’re just maniacs. What were we doing?’

Then you have to pull back from that and say ‘Maybe we shouldn’t have had that weird, super-crazy effect on the vocal.’ It’s a little bit of a balancing act to find the sweet spot.

I read that you opted for a more fast paced approach to the studio time, this time around. How did that influence the sessions? Was it less about trying to get the ‘perfect take’ or less agonising over specific sounds?

Yeah, I think we spent roughly two and a half years making the Down in the Weeds record. Which is a long time to be making a record and thinking about stuff and changing stuff. Adding effects and taking them off and putting them back on.

There’s some imaginative things that are interesting that can happen when you approach it like that. But this one we made probably from start to finish in four or five months – so quite a bit faster. It was intentional because we wanted to just sound more just off the cuff and less manicured.

Some of my other favourite bands are like The Replacements, where it’s like, you can tell they cared, and they did do some interesting production things, but you can tell they weren’t very precious about it. They didn’t take too much time searching for perfection. It was more of just capturing what was happening and that’s it, and then just move on. So that was more of our approach to this one.

I love The Replacements reference. That approach feels like something that drops in and out of music over the years. You hear lots of great records that have that more manicured sound but I find it then becomes really noticeable when a band is just in the moment playing together.

Totally, and I know how it happens because I witnessed it my whole life from making records on four-track to finally getting in a studio with two inch tape machines. Then the dawn of Pro Tools and all of this technology. And you’re right, some really amazing music has come out of that. I’m not anti any of that. I mean, we use Pro Tools. We have tape machines and everything, but it’s more to do with aesthetic choices.

I think that, in a way, some of that older stuff sounds so cool and weird because they didn’t have a way to fix it really easily or anything. They couldn’t just slide the mouse around and make it line up, you know? And you can do that now, but you don’t have to. You can also just be like, ‘Let’s just leave it. Sounds like music.’ But you have to decide that.

I’ve done records like some of my solo stuff and stuff with the Mystic Valley Band. I intentionally didn’t ever get it on a computer. It was all analog and mixed to other analog. And there was no sort of tomfoolery when it came to computer stuff. But that’s not the way Bright Eyes works. Like, [Mike] Mogis loves, [laughs] he loves Pro Tools. He loves all his toys. He loves all his little magic boxes. So I got to let him do his magical power but then be like, ‘okay, let’s just let’s leave that. That’s cool as it is.’ We’re only going to make it worse, the more we try to make it “perfect”.

In terms of your working relationship with Mike [Mogis] and Nate [Walcott], having made a lot of records together by this point – have you noticed that you move back into your similar sort of roles that you had 20 years ago? Or is it something that’s always evolving in the way that you guys just approach studio time together?

It’s kind of a non-answer, but I would say both. Both of those things are true. Like, we’ve all been making music the whole time, whether together or separately. So we have a lot more experience and knowledge and things that we tried that we realised we didn’t like later. We’ve obviously grown, I don’t know if evolved is the right word [laughs], but maybe devolved.

There’s such a shared history and trust and I just don’t have to explain things to them, and they don’t have to explain things to me because we’ve been doing this for so long. I would say our roles are still very similar in the sense of how I write the words and I guess the songs to some degree, although I collaborate with them when I’m writing the songs sometimes.

Nate is just great with all the keyboards and synths and the pianos. He can write amazing orchestral arrangements for like any instrument that we can think of. And then Michael can play basically any stringed instrument: pedal steel, mandolin, electric guitar, banjo.

And then he also is, in my opinion, like one of the greatest producers alive, even though he doesn’t get a lot of credit. His ear is insane, and his ability… I can come up with any sort of abstract idea, and he can figure out a way to manifest it on the actual recording. I can be like, I want this to sound like, you know, a house full of burning children, and he’ll figure out some way to like, make it. I’ve never said that, by the way. [Laughs]

That’s such a relief, Conor. [Laughs]

But you know what I’m saying, you can take weird ideas [to him] and actually make them happen, which is rare. Some people don’t have that much, well one, ability and two, just imagination or willingness to go with a strange idea. Like a lot of producers and a lot of people will shut things down because they’re like, ‘Well, I know that wouldn’t sound good.’ I’m like, how do you know that wouldn’t sound good until we try it? And I think that’s the thing about Michael, is he’s willing to try anything.

That’s so great to hear. Thank you so much for chatting with me today. All the best for the release and for the tour that’s coming up. I know that Bright Eyes fans are going to be so into it. Congratulations!

Five Dice, All Threes is out September 20 via Dead Oceans. You can pre-save the album here, and keep up with Bright Eyes here.