A sonic analysis of one of electronic music's most monumental moments - 'Windowlicker' by Aphex Twin.

On March 22 1999 Richard D. James released a track under his well-known moniker Aphex Twin called ‘Windowlicker.’

Across six minutes, the track sways between awfully out-of-tune synthesisers, jarring vocal samples, chaotic rhythms and awkward sex noises before culminating in a cacaphonic, ear piercing wall of white noise.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

By all means, it’s unlistenable – on paper, it’s the kind of song that would make you squirm in your seat and make your dog uncomfortably pace and howl in the backyard. Some would say it’s one of the greatest electronic tracks ever made.

If you’re familiar with the works of Richard D. James, you’ll know that the man’s a bit of an oddball – in fact, he’s quite possibly one of the most eccentric minds of this generation. In his adolescence, James dabbled in software coding and modifying electronic equipment as a hobby, and began creating music with his array of modified samplers, synthesisers and tape machines at the age of 12.

By the time he was 14, James had started utilising his modified machines and 8-bit computers to record a unique form of music that fused pounding techno rhythms, soaring synth pads, pulsating sequences of ambient noise and reverb-heavy samples from an array of films to create his beloved debut LP: Selected Ambient Works 85-92.

While initially released to a small independent label, Selected Ambient Works 85-92 eventually hurtled Aphex Twin into mainstream consciousness as critics began to catch wind of the record’s genius, with many deeming it responsible for pioneering the genre of Intelligent Dance Music, essentially bridging the gap between the likes of techno auteurs like Jeff Mills and ambient masterminds such as Brian Eno.

In an era where electronic music – particularly acid house and techno – was condemned and ridiculed throughout mainstream media, Aphex Twin proved that electronic music wasn’t just music for nightclubs. Perhaps it could have soul, and stimulate unique discussion. Maybe it could invoke feelings in people without all the negative, drugged-up connotations it was associated with. Maybe it was even the sound of the future after all.

Following the success of Selected Ambient Works 85-92, Richard D. James doubled down on his eclectic musical output, releasing an array of records and creating various pseudonyms such Caustic Window, AFX and Power-Pill in order to constantly release his diverse sonic experiments.

1992 also saw the release of the single ‘Didgeridoo,’ a frenetic fusion of machine gun drums and the distinctive drone of the Aboriginal instrument which somehow managed to reach #55 on the UK Singles charts.

Some would go on to argue that ‘Didgeridoo’ acted as a precursor to the emergence of drum ‘n bass, a genre which Aphex Twin would go on to revisit in subsequent works such as 1996’s Richard D. James Album.

This era also saw the release of Selected Ambient Works Vol. 2 in 1994 – a much more evident foray into ambient music that many consider to be one of the genre’s defining releases – as well as the classical-influenced …I Care Because You Do in 1995, the latter bearing a distorted image of James’ own face which would soon become a recurring theme in subsequent Aphex releases.

However, it was with the release of 1997’s ‘Come To Daddy’ and its accompanying video that made Aphex Twin a household name.

A snarling, brutal drill ‘n bass affair with a terrifying video to match, ‘Come To Daddy’ was originally conceived by James as a drunken death metal parody, with its unprecedented critical and chart success catching him off-guard.

James later expressed his remorse at the success of the single in an interview with Index Magazine – “Come to Daddy’ came about while I was just hanging around my house, getting pissed and doing this crappy death metal jingle. Then it got marketed and a video was made, and this little idea that I had, which was a joke, turned into something huge. It wasn’t right at all.”

Almost 18 months after the release of ‘Come To Daddy,’ Aphex Twin returned with ‘Windowlicker.’

A nauseous sonic odyssey that fuses James’ digitally processed vocals with wonky drum rhythms, rolling snares, a deceptively simple synthesiser chord progression and oddball samples before concluding in an ecstatic wall of distortion, it’s difficult to place a finger on what’s just so special about ‘Windowlicker.’

Some elements of the track sound incredibly organic and warm, while other parts simply sound cold and sterile – a contrast which seems to be a recurring theme throughout Aphex Twin’s music. It’s almost as if an alien from outer space was explained the fundamentals of manmade music and then created an electronic track without ever listening to one prior.

In a nutshell, ‘Windowlicker’ essentially packages everything great about Aphex Twin’s output from the ’90s into one track, and its impact was instant.

In the year of its release, NME crowned ‘Windowlicker’ as the best single of 1999, and Pitchfork later ranked it above the likes of Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ in its Top 200 Tracks Of The ’90s, while the song peaked at number 16 on the UK Singles Charts.

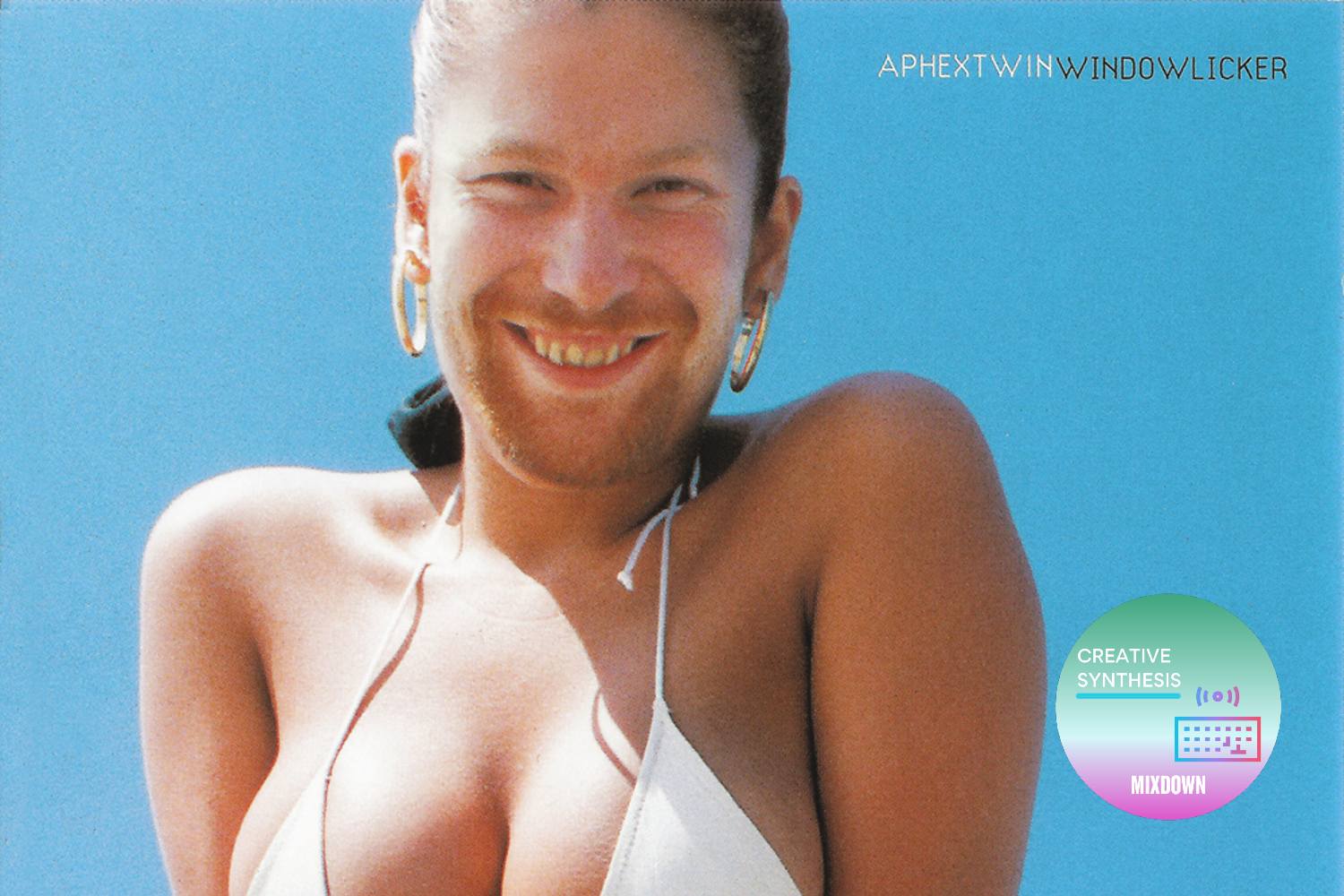

‘Windowlicker’ was also matched with a brilliantly bizarre ten minute music video which saw James team up once again with ‘Come To Daddy’ director Chris Cunningham to create a tongue-in-cheek parody of a lavish late ’90s rap video.

The infamous video features 127 instances of profanities and racial slurs within the first four minutes of its runtime, as well as a number of shots of overtly sexualized, bikini clad models superimposed with James’ signature twisted grin on their faces.

Despite it obviously being a parody of clips by the likes of Puff Daddy and Hype Williams, Cunningham and James’ ‘Windowlicker’ video was subject to significant critical analysis from various cinematic and literary fields, with many criticizing seemingly problematic portrayals of sexism and race throughout the clip – mainly due to the fact that the video was spearheaded by two white British men.

Nevertheless, ‘Windowlicker’ would go on to be nominated for Best Music Video at the 2000 Brit Awards, and is still celebrated as one of the best music videos of the ’90s.

In retrospect, it’s safe to assume that the braver, more experimental side of electronic music would be in a much different place today without ‘Windowlicker.’

The legacy of the track can be heard prominently throughout the fabric of Flying Lotus, Oneohtrix Point Never and Jon Hopkins’ musical output, and its influence is audible even in the works of James Blake, Death Grips, Grimes and Flume at their weirdest.

Twenty years on, it’s hard to deny the influence and legacy left by ‘Windowlicker’ – despite a huge shift in technology and the creation of electronic music, ‘Windowlicker’ still sounds like it’s one of the most progressive pieces of music ever produced.

Long live Richard D. James – may your music continue to challenge, terrify and inspire the zeitgest for years to come.

This article was originally published on March 20, 2019.

Revisit Aphex Twin’s musical collaboration with Korg here.