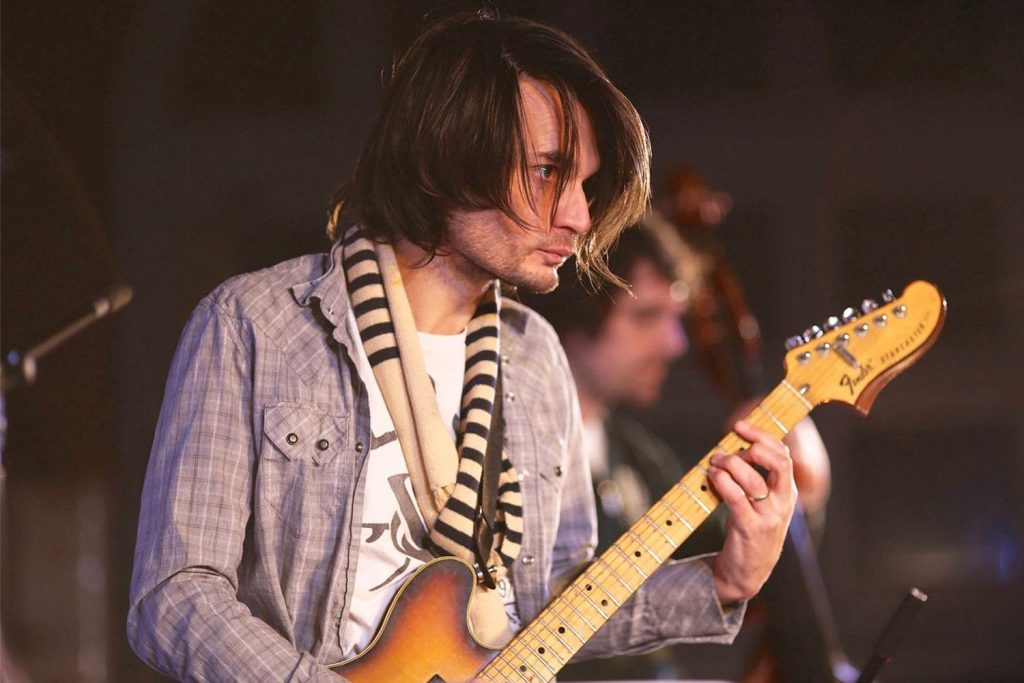

The seminal producer reminisces on making the biggest Australian alternative album of the '90s.

After a string of breakout EPs culminated in the group regrouping to Thailand to record their debut LP Tu Plang in 1996, Regurgitator released their highly successful sophomore album Unit in November 1997.

The album signalled a new direction for the band with a style that could broadly be described as a fusion of ’80s synth-pop and alternative rock. It was wildly successful, receiving overwhelmingly positive reviews and delivering five songs which crossed the band over into the commercial mainstream. Unit also went on to win five ARIA awards, including Album of the Year and Producer of the Year in 1998.

The band and the album’s producer Lachlan Goold (AKA Magoo) broke with convention at the time by setting up their own warehouse studio in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley, with the space subsequently becoming known as The Dirty Room.

The production ethos behind Unit went on to prove that it was entirely possible to produce a commercially successful album using a “do-it-yourself” attitude and low-cost digital production tools – something that totally unheard of in an era where 24 track analogue tape studios were still very much the standard in the industry.

What was it that brewed up this perfect storm of success? We recently had the opportunity to catch up with Magoo to discuss the project, and the process behind the recording of Unit.

What motivated yourself and the band at that time to set-up a recording space in that way?

Magoo: “A lot of it was motivated by Martin, the drummer. He had a very good business mind, and he drove the concept of going ‘why give the money to a commercial facility when we can actually buy gear that’s good enough’.

“The Prodigy’s Fat of the Land came out just before Unit and the band were reading about how they had used ADAT and Mackie, and it just kind of opened a door for them… (Suddenly) it felt like it was possible to do it all yourself.”

Delving further into the technical specifics of the project, what equipment was involved in the recording?

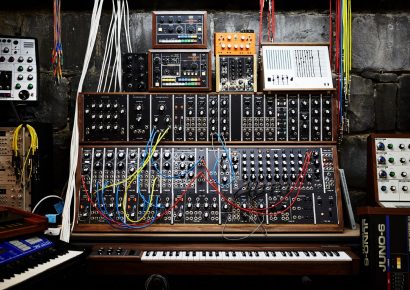

Magoo: “Martin had a 24 channel 8 buss Mackie and an ADAT. Then with the advance they bought two more ADATs, so that we could have 24 tracks.

“I had an AKAI S3000 sampler, as did Quan. Then we hired a Mac Quadra to run Cubase, a rack of eight Neve 1073s and a Neuman U47 FET. The band bought an Eventide Harmonizer and a Nord Lead 1 keyboard. The sound of that record is really the Nord Lead keyboard – it’s all over it.

“We had to wire up all the patch bays as well so that we could run it all. We also had the Mackie automation. You put it on the inserts of the Mackie, and it gave you a balanced send and return. You got a fader pack and a software package over the top where could do automated fader moves and mutes.”

Did you mix the album in the space as well?

Magoo: “We mixed it in the space there, which was probably crazy, but part of that record actually led to the way that I worked for a long time after that.

“When we started, they only had four songs. During Tu Plang, they had all the songs, and they had done their own demos, but the record company made them re-record more demos at Red Zeds studios. They just got sick of the songs by the time it came to record the final versions.

“With some of the songs, the demos were better on Tu Plang, just because they were fresher. They would do the songs in a different version just because they were sick of how they were doing it on the demo, not because it was better.

“Before Unit there was four songs. We set-up and recorded the four songs and then they said what are we going to do now? So, then I mixed while they wrote more songs. Ben wrote two songs and Quan wrote two songs and I mixed them. Then we started going song by song, recording and mixing as we went. We couldn’t have done that in a commercial facility.”

So, you had a lot more creative freedom and flexibility essentially?

Magoo: “If we didn’t do what we did, after doing Tu Plang in Bangkok as well, I don’t think they could have gone to Sydney or Melbourne to make the record. It felt like it had to be one up, and some would argue it was one step back rather than up, but it was more about the creative freedom it allowed.

“The gear influenced the sound of course. The mixes capture the energy sonically… I think capturing the essence was more important than the fidelity… which has probably always been my thing anyway. I guess we all had that in common. We wanted it to feel right and if it sounded right that was a bonus.

“I think it was the circumstance that influenced the sound of the album. It was the time. Some people like going into the studio and banging out a record in three or four days. A lot of people like to have time and finesse it. We had the luxury of recording a song and then go it’s not quite the direction we want and then record it again”.

Revisit our discussion with legendary Australian record producer and engineer Mark Opitz.