Streaming economics and TikTok's viral power are pushing songs shorter than ever, with chart-toppers now averaging under three minutes.

Size, it seems, does matter—especially when it comes to writing hit songs.

In a world that is dominated by streaming and short, attention-grabbing content, it’s clear that the shorter the song, the more likely it is to rise to the top. Bart Schoudel, a GRAMMY-nominated producer and engineer who worked on Charli XCX’s Brat told Billboard, “The shorter the song is, the more streams it’s going to get”.

Schoudel advises that these days, talent scouts who plough through dozens and dozens of demos tend to impatiently pass over songs that drag their way to the hook—implying short and snappy is what they’re looking for.

Founder of Perth-based Perfect Pitch Publishing, Clive Hodson, states that royalties from Spotify are “based on a minimum listening of 30 seconds”. “The shorter the song, the more opportunity you get for more streams, particularly with their ruling that you have to have 10,000 global streams in the last month earn any royalties at all.”

Catch up on all the latest features and interviews here.

Aside from the length, Hodson also emphasises the importance of a memorable hook or a standout instrument—like the bagpipes on AC/DC’s “It’s A Long Way To The Top.”

“It becomes an earworm, which is so important. You’ll walk down the street, and it comes into your head, and you go, ‘Where the hell did that come from?’ That’s what you strive for when you’re writing.”

The history of rock is littered with songwriters who hadn’t realised they had written a classic. What does Oasis’ “Wonderwall”, Guns N’ Roses’ “Sweet Child O’ Mine”, The Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”, GangGAJANG’s “Sounds Of Then (This Is Australia)”, The Angels’ “Will I Ever See Your Face Again”, Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, John Mellencamp’s “Jack And Diane”, REM’s “Shiny Happy People” and the Small Faces’ “Lazy Sunday” have in common?

Their writers never rated them particularly high—in fact, they often dismiss the tracks as filler. Yet these songs went on to become evergreens and perennial royalty generators, with many finding lucrative second lives through advertising campaigns.

Advertising sync gravitates toward shorter tracks because they pack so much into just a few minutes. For Australian and New Zealand songwriters, the money can be monumental. Neil Finn is rumoured to have received well over a million dollars when New Zealand’s tourism board licensed “Don’t Dream It’s Over”. The Swingers, who’d fallen on hard financial times, were reportedly happy to pocket a six-figure sum for each of the three years that their sole hit “Counting the Beat” was used by Kmart in a Lemon Paeroa soft drink in New Zealand. The story goes that the late Peter Allen’s estate earned seven figures for each year that Qantas has used “I Still Call Australia Home”. His Australian publisher called the figure “exaggerated” but agreed the deal was still a substantial one.

The Who’s Pete Townshend received a six-figure sum for each of the three years that their song “Who Are You” was used by Who Magazine in Australia. Moby was paid handsomely for Sydney’s Star Casino use of a snippet of a song. The numbers rise considerably if the act and the song are high-profile. The Rolling Stones charged Microsoft millions to use “Start Me Up” for the worldwide launch of Windows 95.

Songwriters may say, “I’ve got the perfect song for an ad,” but it’s not as simple as writing a song about a car and expecting Ford or Mitsubishi to call. “There is no rhyme and reason,” Clive Hodson agrees. “If a brief comes up for a song like that, it gets in. I say to my writers, There’s no such thing as ‘perfect for sync’… until something happens and it’s in a TV ad, or a film or TV series, then it’s perfect for sync!”

TikTok’s influence on song length cannot be overstated. With 1.59 billion monthly active users worldwide as of February 2025, and Australian users jumping from 5 million in 2023 to 8.5 million this year, the platform has become a kingmaker for tracks. The trick with TikTok is to get a track to go viral. The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights”, which broke through on the platform, went on to hit the 4 billion mark streaming on Spotify and is estimated to have made him tens of millions. It stayed in the charts for a year, and at #1 in America for four weeks.

“I’ll never stop being humbled by anything I create making its way to millions of people, let alone billions,” he said.

Jason Falls, a senior influence strategist at Cornett, said in an interview with Billboard that because of TikTok’s “addictive mechanism”, users spend a lot of time on the platform scrolling and finding music (new and old).

“As you flip through different channels, if one song, particularly in a challenge, goes viral, now you’re listening to that same 15 seconds over and over again. It’s the earworm that gets in your head, and then you go buy it or download it on Spotify.”

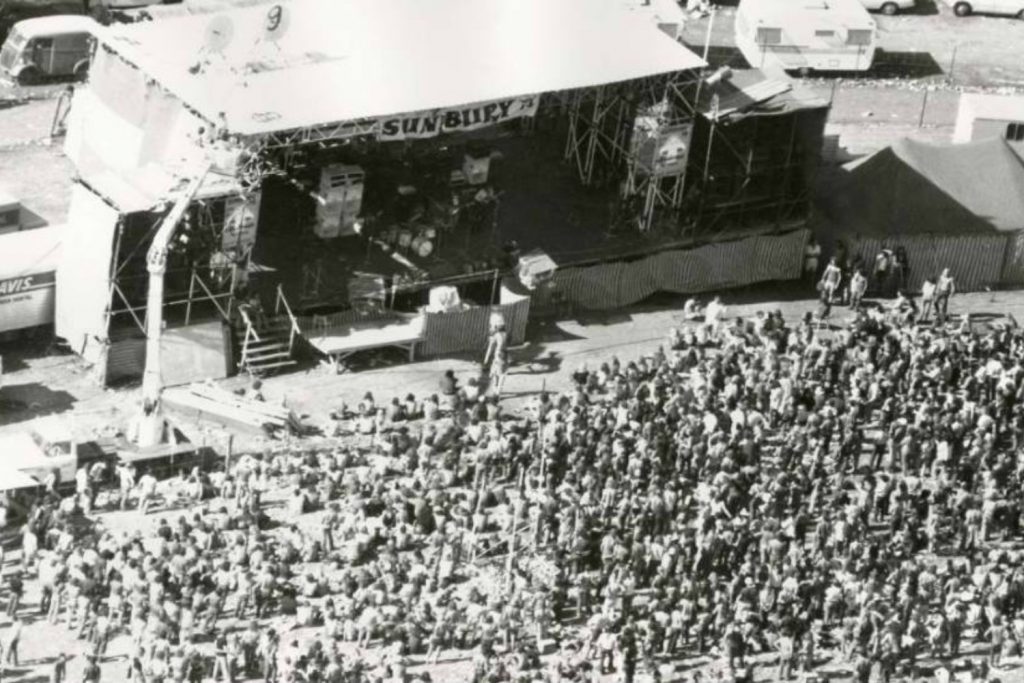

The length of the single was determined from the rock era (from the 1950s) by a combination of tech and radio. Shellac and vinyl records could hold only 3-5 minutes of music on each side. Radio, all-powerful in those days, insisted on telling artists and their producers that shorter cuts meant they could squeeze in more music in between the ads. So the great American rock and roll classics found their way on to Australian Radio.

These included Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel” (2:02), Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” (2:10), Bill Haley & The Comets’ “Rock Around The Clock” (2:00), Jerry Lee Lewis’ “Great Balls Of Fire” (1:58) and Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” (2:39).

Australia’s first rocker Johnny O’Keefe had the shortest song to top the Aussie charts with “Own True Self” (1959) spanning 1:44 In the early ’60s, the practice continued with The Beatles’ “She Loves You” (2:19) “I Saw Her Standing There” (2:55), The Beach Boys’ “Surfing USA” (2:29) and “I Get Around” (2:12).

By the mid-’60s, the popularity of cassettes and, more notably, LSD and albums as a major medium, saw songwriters and record producers break the verse-chorus-verse format and find more freedom with what made a single. Radio then had to contend with mini-epics as The Beatles’ “Hey Jude” (7:12), Russell Morris’ “The Real Thing” (6:20), Barry Ryan’s “Eloise” (5:50), Richard Harris’ “MacArthur Park” (7:21), Stevie Wright’s “Evie Pts 1, 2 & 3” (11:11) and Don McLean’s “American Pie” (8:42).

The coming of FM radio meant longer tracks were acceptable. The advent of CDs and then streaming allowed tracks to be as long as they wanted. Songwriters are divided as to how long a song should be. “Don’t bore us, get to the chorus, stupid,” is one creed among some publishers.

PinkPantheress, whose songs on her 2021 album To Hell With It averaged 1 minute and 18 seconds (1:18), told ABC News: “A song doesn’t need to be longer than two minutes 30 seconds. We don’t need to repeat a verse. We don’t need to have a bridge. We don’t need it! We don’t need a long outro.” But Lady Gaga represents writers on the other side of the spectrum who see composing as a solely creative thing, and that listeners won’t get bored if the track is compelling enough. “Whatever length the artist wants is the perfect length,” she insists.

Chartmetric’s 2024 Year in Music Report showed the average Spotify charting song was around 3 minutes long—nearly 15 seconds shorter than in 2023 and 30 seconds shorter than in 2019. In the ARIA top 10 end-of-year singles chart, six tracks were under 2 minutes, and two others just crossed the 3 minute mark. The average Billboard Hot 100 song clocked in at 3:30, down 8.6% from 3:50. In addition, five or six years ago, 1% of hit songs ran 2.5 minutes. Now 6% of all hits are 2:30 seconds. If you look specifically at the tracks that topped the Billboard Hot 100, these have decreased by around 18%, from 4:22 in 1990 to 3:34 in 2024.

At the 2024 Grammys, nearly 20% of songs were under three minutes. At the 2025 Grammys, two Record of the Year nominees were Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso” at 2:55 and Charli xcx’s “360,” at 2:13. In early 2025, Jack Black’s “Steve’s Lava Chicken” made chart history in Australia. From the A Minecraft Movie, it ran just 34 seconds, and the shortest track to make the local charts. It reached #71 and created a stir within gamers. The song was written by Black with the film’s director Jared Hess for a scene where Black’s character Steve cooks a chicken by pouring lava on it.

The track set a record in the USA’s Hot 100 and the UK Singles Chart. “Steve’s Lava Chicken” debuted at #78 in America and was streamed 2.5 million times, certifying it gold. In the UK it peaked at #9 on its third week. Black said at the time, “I want to send big love to all the Minecraft fans for getting us up there – it’s insane! Love you!”