Slipstream is a completely DIY effort, capturing Chuck Sics' unique ability to blend atmospheric layers with his trademark self-aware lyricism.

There’s something quietly defiant about an artist who shapes every element of their music. Sydney’s Chuck Sics has done just that with his debut EP Slipstream, and the result is a collection of lush, atmospheric tracks that are both expansive and intimate.

A DIY record is no easy feat. For someone who writes, mixes and produces their own music, knowing when a track is finished can feel like an endless puzzle – there’s always one more tweak tempting you back to the desk.”Mixing a song for me is like constantly noticing little imperfections that bother me that then I have to fix,” Sics admits. “I spend day after day making lists of problems to fix and then adding new ones that I notice.”

Catch up on all the latest features and interviews here.

So how does he let go? “I think the rate at which I noticed imperfections with them eventually slowed down long enough for me to be happy to release them. I still notice new things I have a problem with occasionally, but overall I’m pretty happy.”

His perspective on the finished work is refreshingly grounded. “There are plenty of things I would do differently now, but when I look at this music as if it’s a manifestation of a past self, I feel kinda nice about it. It’s like an old photo where you might not love how you look, but you’re having a good time, so it’s nice.”

At the heart of Slipstream sits a drum kit that, by Sics’ own admission, sounded “pretty awful to begin with.” He decided to sample his friend River’s kit – but quickly discovered that polished samples weren’t going to cut it.

“I had tried using other samples and found they always sounded too good, and because of that, they sounded unreal,” he explains. “So I spent a day recording my own samples and programming them into an instrument on the Logic sampler. I used a cheap microphone in a bad room, so they actually sounded pretty awful to begin with – I had to do a lot to make them sound right.”

This philosophy of intentional degradation extended across the entire record. “I kind of did that with everything on the record. I was never happy with how something sounded straight away – I always felt like I had to mess it up in some way.”

The breakthrough came during work on “I’ve Been Thinking”. “I had just sampled a whole kit and programmed it into a MIDI instrument, gave it a bit of mixing, and I decided that would be the drum sound for the whole record,” Sics recalls. “It felt like the perfect sound for what I was going for, and it really inspired me to make the rest of the songs.

Sics kept this up with a deliberately heavy-handed approach to processing. “I really overcooked everything, somewhat intentionally,” he says. “I compressed and saturated everything heaps and often would put a lot of that stuff after things like delay or chorus effects. I wanted everything to sound like it was coming out of the same machine.”

While most of the EP tracks evolved gradually, “Slipstream” itself was a last-minute addition that transformed the entire project. “My label said they felt like the EP could use one more song, and I decided on a whim it should be this one,” Sics explains. “When that was finished, I felt like it really elevated the whole project, or at least provided it with one more different musical perspective. Everything sounded fresher to me after that was put in there.”

Not every track required such evolution. “M.A.D” and “Alone on a Plane” were what Sics calls “flukes” – songs where everything clicked immediately. “Everything just felt right about them to begin with. I think that’s why I like those the most, funnily enough.”

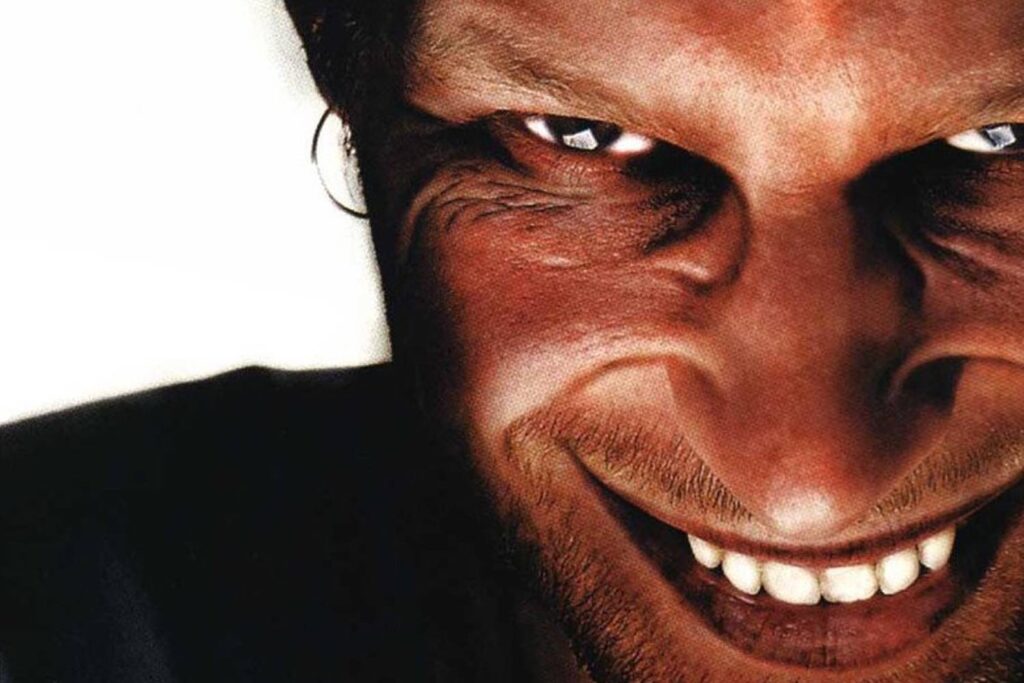

Possibly the most fascinating insight into Sics’ creative process is his synaesthetic relationship with his music. When designing the artwork for Slipstream, he kept gravitating toward blue, green, and red – until he realised why.

“I was staring at Logic Pro X on a computer screen which had blue audio tracks, green MIDI tracks, and when you hit record on any of those tracks, they go red,” he explains. “And those colours are what this music sounds like to me. I’d be curious to see what colour my music sounds like when I’ve been looking at something else while I’m making it.”

It’s a reminder that visuals and sound exist in constant dialogue. “I think it’s impossible to disconnect the two,” Sics notes. “What you see has such an impact on what you hear, so I do wonder what other people see of me and my music and how it affects how they listen to it – I think about it all the time with every artist I see.”

Chuck speaks of translating his self-made songs into a live, full-band show. “Something I love about playing these songs with the band is that the music becomes what it was always supposed to be – band music,” he says. “Each of them plays stuff their own way, and together we just make a different sound. There are a few intentional adaptations to make things exciting, but what I love most is hearing how each of them puts their spin on things.”

For artists considering the full DIY route, Sics offers a balanced perspective born from experience. “I will say that it feels really good to feel self-sufficient in making music. I spent a long time waiting around for other people to help me with stuff, and eventually I decided to learn how to do all the stuff to the best of my ability. It has made me feel very connected to the music, but it can be very frustrating and taxing on your sanity.”

If there’s a piece of advice to take on, it’s this: “Be easy on yourself, be hard on yourself, don’t slack off and don’t burn out.”