Analysing Alex Winter's look at one of the most provocative minds in music.

What does it mean to be successful as a creative individual? Does success entail using one’s creativity to write a plethora of easily accessible FM radio rock tunes, with the aim of selling countless records and accumulating shitloads of money?

For a band such as the Eagles, for sure. Or does it entail using one’s literary talents to embed messages of social cohesion within their music, with the aim of procuring some semblance of collective progress? For an artist such as Bob Dylan, most definitely.

For Frank Zappa, however, success simply meant writing and performing music that he found fulfilling.

Never miss an update – sign up to our newsletter for all the latest news, reviews, features and giveaways.

Zappa

Alex Winter’s latest documentary, simply entitled Zappa, explores the life and extraordinarily vast output of a complicated, obsessive genius — one who vehemently rejected the very idea of commercial success, and displayed a scathing cynicism towards the capitalistic forces that drove the music industry in the United States.

With access to a cache of unseen live concert footage, interviews and home videos, Winter carefully weaves together these pieces of material throughout the course of the two hours, mindful not to rely too heavily on one resource above another. The result is perhaps the rawest depiction thus far of a supremely talented yet seemingly aloof man who devoted his life to one sole cause: music.

The film begins with footage of Zappa’s final rock performance in 1991: “This is the first time I’ve had a reason to play my guitar in three years”, the ailing composer tells a raucous crowd of Czech fans who had only recently been freed from Soviet rule. A cult-like figure in the eastern-European nation, Zappa vociferously instructs the crowd to “keep it unique”: a mantra that defined his very aesthetic.

The way in which Winter elects to unfurl the documentary chronologically is fitting, given the number of twists and turns that defined much of Zappa’s working career. The film details the success and then inevitable implosion of his first band, The Mothers, as former band members recall the sometimes unrealistic expectations foisted upon them by their quasi-dictatorial bandleader.

Guitarist Steve Vai, who played with Zappa throughout the early ‘80s, recounts a sentiment shared by numerous former colleagues: that they were merely “tools” used by the composer in order to realise the unrelenting stream of his internalised musical conceptions.

Not that Zappa would have flatly denied this, either. In one archived interview, he openly admits that he writes music so that he can hear his own ideas being performed. And if members of the public happen to enjoy it, then that’s even better.

As an avid Zappa fan, I couldn’t help but feel that the film glossed over the contributions of certain band members, particularly those who played on classic LPs such as Apostrophe (1974), Sheik Yerbouti and the three-part rock opera Joe’s Garage (both 1979).

Keyboard pioneer George Duke, drummer Vinnie Colaiuta and the vastly underrated multi-instrumentalist Terry Bozzio are all merely mentioned in passing, making you contemplate how different Zappa’s mid-‘70s output would have sounded were it not for the tactful virtuosity these musicians brought to the mix.

However, Winter does well to highlight Zappa’s status as one of the world’s first truly independent musicians — not solely in a musical sense, but also with regards to the business side of things. As someone who harboured a bottomless disdain for the manipulative and misleading practices of the US music industry, Zappa decided to found his own, self-titled record label in 1977.

The composer’s rejection of the entire ethos that drives the industry is palpable: “The whole idea of selling large numbers of items in order to determine quality is what’s really repulsive about it”.

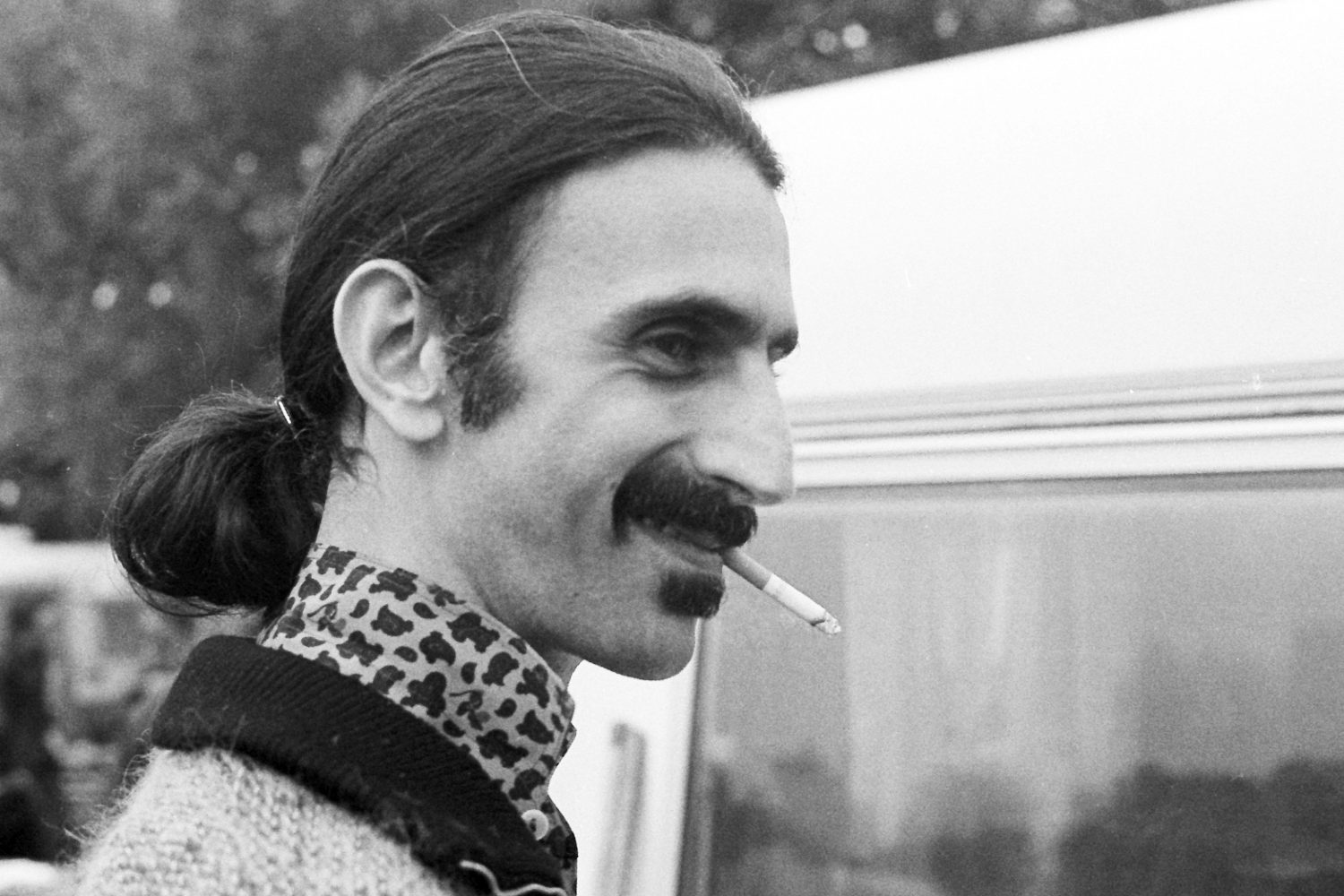

Perhaps you might be wondering why I’m referring to Zappa as a composer, rather than a songwriter or guitarist — even a cursory viewing of the documentary would do well to illustrate Zappa’s profound passion for avant-garde orchestral composition. In fact, the majority of photographs shown throughout the feature depict Zappa smoking a cigarette while intently hunched over leaves of manuscript paper.

Winter’s portrayal of the final chapter of Zappa’s life is easily the most emotional part of the film, as he comes to terms with his cancer and impending mortality. All the while, he is steadfast on bringing some of his most significant compositional inventions to life, utilising the talents of the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

The inclusion of footage from these rehearsals is, in my opinion, the zenith of the documentary. Though greying and visibly frail, Zappa conducts the orchestra with an electric dynamism that many conductors would struggle to muster. One can’t help but be taken aback by the dissonant yet iridescent qualities of not only the music, but the man himself.

Zappa is now screening in Australian cinemas. Find out more here.