Sometimes, size does matter.

Australians make the worst historians. You can put that on the coat of arms.

Whether it’s a by-product of colonialism, the cultural cringe or us failing to see our perceived cultural value in the face of an ever expanding global economy (my money is on the latter), there is little denying our tendency to let local history slip by the wayside.

Read more gear features here.

This especially rings true in the fickle world of musical subcultures, where locally borne movements tend to bubble under the surface for a period before quickly being extinguished to make way for the next big import or the next big repurposing of the 808.

But this wasn’t always the case.

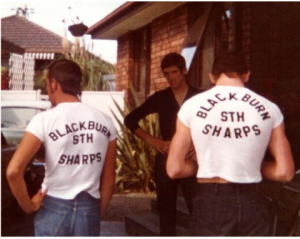

The Sharpies were an army of homegrown proto-punks who ruled the working class suburbs of Melbourne and Sydney from the mid ’60s right through to the late ’70s, but whose influence can still be heard in a bunch of bands of the current era (ECSR, Amyl & The Sniffers, POWER etc.).

A truly endemic subculture with its own customs and conventions, the Sharpies were a welcome antidote to the squeaky-clean prosperity and rampant consumerism of post-war Australia. So called for their ‘Sharp’ appearance, the Sharpie uniform of shaved head/mudflap mullet and boots was almost as striking as their choice in music: ragged, locally-produced guitar boogie played at unspeakably high volume.

This was during a period where the battle for wattage was in full swing, with many local PA systems struggling to compete with the ever-increasing venue sizes brought about by the sudden influx of gig-going sharpie youth.

In turn, this meant a requirement for more stage volume, as local builders sweated schematics and hacked popular overseas designs to extract everything they could out of the humble guitar amp. The resulting arms race would give birth to some of the loudest guitar amps to ever roll out of any factory, anywhere.

Almost like a bogan answer to the Jamaican sound system, these amps were big, ugly and designed to operate at extremely high output: the perfect approach for a country with a lot of space and not a lot of neighbours. So with our earplugs in and everything set to eleven, here is our guide to some of the biggest, baddest Antipodean oddities of the Sharpie Era.

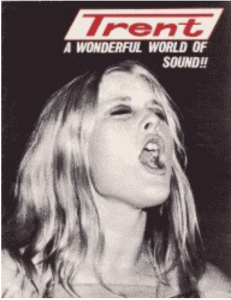

Trent Wildcat D

An early pioneer for big amps the world over, Trent were a brand with something to prove. When The Monkees reached out and commissioned the local manufacturer to provide the backline for their 1968 Australian tour, Trent knew their reputation was on the line.

Not wanting another Shea Stadium on their hands, the Brisbane builder did what any self-respecting Aussie would do in the face of mounting international pressure-they got to work building some of the largest production guitar amplifiers in the world, one of which was the infamous Wildcat D.

Consisting of a 300 watt head paired with dual 8 x 12” cabinets (for a total of 16 speakers in all) the Wildcat D was an obnoxiously loud prospect from the get-go. For further reference, just check out the below sales pitch (taken from the original Trent catalogue):

‘It’s stupendous. If it is used without discretion the eardrums are in danger of permanent damage. It will overcome the screaming of teenyboppers for the popular large group, and project over a huge area.’

Damn teenyboppers.

Now, this was precisely the kind of amplifier that you did not want in the wrong hands, but as the ’60s turned into the ’70s and common sense fell by the wayside, the Wildcat D found itself a new purpose – facilitating the deafening three-chord boogie of the Melbourne Sharps.

This was an amplifier designed to be played in the middle of the MCG, to crowds in the tens of thousands and now it was being loaded into dance halls and medium sized venues by punky looking kids with mullets, shaking foundations and rattling eardrums – all in the name of a good time.

With its era appropriate red tolex and looking like the robot maid from The Jetsons, the Wildcat D was the beginning of Australia’s fascination with the loud and overblown, kick-starting the big amp movement that would go on to have an influence on so many Sharpie and Pub Rock bands that followed in the decade to come.

With the Wildcat D, the bar had now been set and while Trent would remain a prominent name in the years to come, it was a small independent builder from south of the border who would take our natural inclination for monolithic amps and inject it with the kind of sick Ozploitative bent that would come to define the big amp era. And that brand was Strauss.

Strauss Warrior

Gary Nessel and John Woodhead started Strauss Amplifiers in 1962 in South Yarra, at a time where jangly instrumental acts like The Atlantics and The Denvermen were in vogue. It didn’t take long for the fledgling brand to pick up momentum, and by the mid ’60s the duo were opening a storefront on Princes Bridge (now the site of Federation Square), right in the heart of Melbourne’s city centre.

Manufacturing guitar, bass, and PA amps (the latter of which proved a big influence on their guitar amp designs moving forward), Strauss quickly moved away from the small combo amps that typified the early years of the brand, adopting the ‘bigger is better’ mantra as early as the late ’60s.

This new found commitment to big amps with big wattage positioned Strauss as one of the leading figures of the local amp wars of the early ’70s, taking the concept of the mega-amp and riding it out to its logical conclusion.

That ‘logical’ conclusion was the Strauss Warrior, a 350w all-valve guitar amp. Yes you read that correctly. This wasn’t a repurposed Bass or PA rig, this was a purpose built, guitar specific, 350w monstrosity made to put Sharpie royalty like Lobby Lloyd and Billy Thorpe at the very top of the mountain (or at least, Sunbury).

Weighing in at a metric shit tonne and with enough wattage to power a small suburb, the Warrior was a logistics nightmare by the standards of today.

‘It was like the La Trobe power station’, noted Lloyd’s longtime running mate and fellow Coloured Balls guitarist, Ian ‘Bobsy’ Millar.

‘Lob would have about 32 twelve inch speakers stacked up and I’d have about 15. Those Strauss amps definitely put out a lot of power in that regard.’

Boasting no fewer than six KT-88 valves in its bulky head unit and frequently paired with a ridiculous number of speaker cabs (no less than four 8x12s being the norm) – the Warrior was anything but portable, often requiring its own bump in/bump out procedure independent of anything else going on that evening.

Combine this with its tendency to chew through valves and speaker cones at an alarming rate and it quickly became almost a full time job-transporting, assembling and maintaining the monster Aussie rig.

In terms of sheer volume, the Warrior was (by all accounts) absolutely devastating. Just have a listen to this ABC TV broadcast of Loyde and the Coloured Balls from ’73. Keep in mind that these are some of the highest calibre broadcast engineers in the country, operating some of the best equipment money can buy. They don’t even come close to containing the spill.

Strauss Polka

The ‘conservative’ little brother to the brands ludicrous 350w Warrior amp, the Polka was nonetheless 200 watts of vicious Aussie tone, and is still an utterly monstrous amp by the limp-wristed, combo-centric standards of today.

With four KT88s under the donk and utilising the same dual drive stage/massive output transformer employed in other thunderous Aussie amps of the era, the Polka was as close to ‘Studio Amp’ as the Sharpies got – a portable, lower wattage option for that rare occasion where 350 watts might be a tad overkill (but still with enough raw power to tear the local RSL a new one).

With the head unit alone weighing a back-breaking 21kg and with an output transformer akin to something out of a Holden Monaro, the all-valve Polka is a perfect example of Australian brutish ingenuity, becoming something a staple through the 1970s before being decommissioned and banished to the garage after the volume wars subsided and everyone came back to their senses.

Other than being an extremely large amp that somehow feels small, another interesting aspect of the Polka was that it was one of the first Australian amps to gain truly nationwide approval, transcending its Melbourne locale and becoming a popular model in music stores across the country. The legacy and popularity of iconic Strauss models like the Polka was enough to see a relaunch of the brand in the early 2010s.

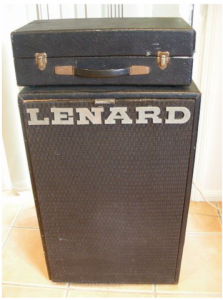

Lenard GB200

While Strauss emerged as the biggest name in local amps, they definitely weren’t the only show in town and up in Sydney it was a very different story (as it usually is).

After all, the Australian amp industry was birthed from scatterings of grassroots builders, at a time were custom PA and guitar amp were very closely interlinked. This meant that many amps of this era were built to spec or with specific backlines or in mind.

Prior to the Polka, little thought had been put into distributing these amps on a national scale and as a result, the domestic amp industry was for the most part, extremely provincial. Every city had their builder, for Melbourne it was Strauss, Brisbane had Trent/Vase and for Sydney, Lenard ruled the roost.

An early pioneer in sound reinforcement, the Sydney brand quickly became a go-to for touring international artists, providing amps and PA’s for the rotating cast of big name touring acts, visiting our shores in the late ’60s / early ’70s.

This led to the company producing more and more one-off guitar and bass rigs and before long they were churning out a slew of big wattage production amps out of their Cammaray factory, one of which was the GB200.

Suitable for both guitar and bass, the GB200 featured a particularly unique layout, with valves laid on their side under a perforated metal top, in turn providing amazing ventilation for the four (often overworked) 6CA7’s located beneath the grille.

This unorthodox setup meant that a ‘flip-top’ road case could be directly built into the chassis, a curious design feature for the time, but one that was particularly warranted given the GB200’s heightened sensitivity to beer spillage and the various other occupational hazards that came with the pub rock/Sharpie lifestyle.

Capable of going from sweet whisper to guttural roar often in the same musical phrase, the GB200 was an extremely dynamic, extremely tasteful amplifier, prized for its relative portability and quiet running noise.

Its outstanding projection and extreme volume, a trait no doubt enhanced by the brands continued use of the legendary E-tone speaker in their cabs, made the GB200 one of the most sought after Aussie amps of the late ’60s / early ’70s.

Sadly, the open air design of the GB200, coupled with many years of hard living, has meant that very few of the original GB200 units made it out of the ’70s alive. Its next of kin, the closed cab SGB200 version, still occasionally pops up from time to time on eBay or on vintage guitar groups: but even then, these are usually missing the original cab or are covered in tasteless ’90s band stickers (a recurring theme amongst a lot of vintage Aussie gear).

Holden / Wasp 200XL

Another Sydney-sider, Holden/Wasp was a cross-pollination between the NZ based manufacturer Holden Amplification and Sydney-based Wasp Industries.

Originally forming in the late ’60s to give the big British manufacturers some much needed competition, the Holden/Wasp partnership would quickly evolve from imitation to innovation, integrating some very Australian design cues into their bastard take on the classic British stack.

In keeping in line with the local thirst for high voltage rock and roll, Holden/WASP were one of the first manufacturers to offer super-sized 200 watt variants on their amps, a sales tactic that proved popular for many Australian manufacturers at the time.

The 200XL is particularly noteworthy for its weirdo topology, which employed an additional drive stage directly after the phase inverter (as a design, is something rarely encountered outside of ’70s Australia, even to this day).

The inclusion of this additional drive stage would later be echoed in releases from Eminar and Strauss, in turn becoming one of the hallmarks of the Australian sound that typified the Sharpie Era.

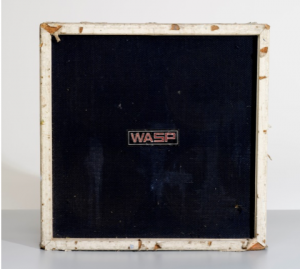

Deniz Tek’s (Radio Birdman) original Wasp cabinet.

Combine this with the 200XL’s four 6550 power tubes and the brands knack for producing some of the finest cabs of the era, the majority of which employed locally produced Rola/Plessey speakers, and you had all the makings for an extremely loud, extremely colloquial sounding rig.

With their reputation for technical consistency and bombproof reliability, It didn’t take long for the Wasp logo to become a familiar sight across stages all through Sydney and Brisbane (Melbourne was still very much a Strauss/Eminar town).

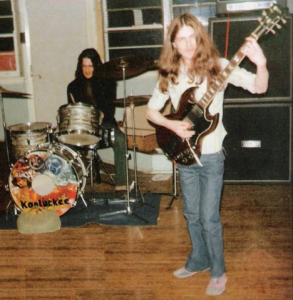

Peep the below photo of Angus looking very um… Young, putting his Wasp through its paces in Sydney, back in the early ’70s.

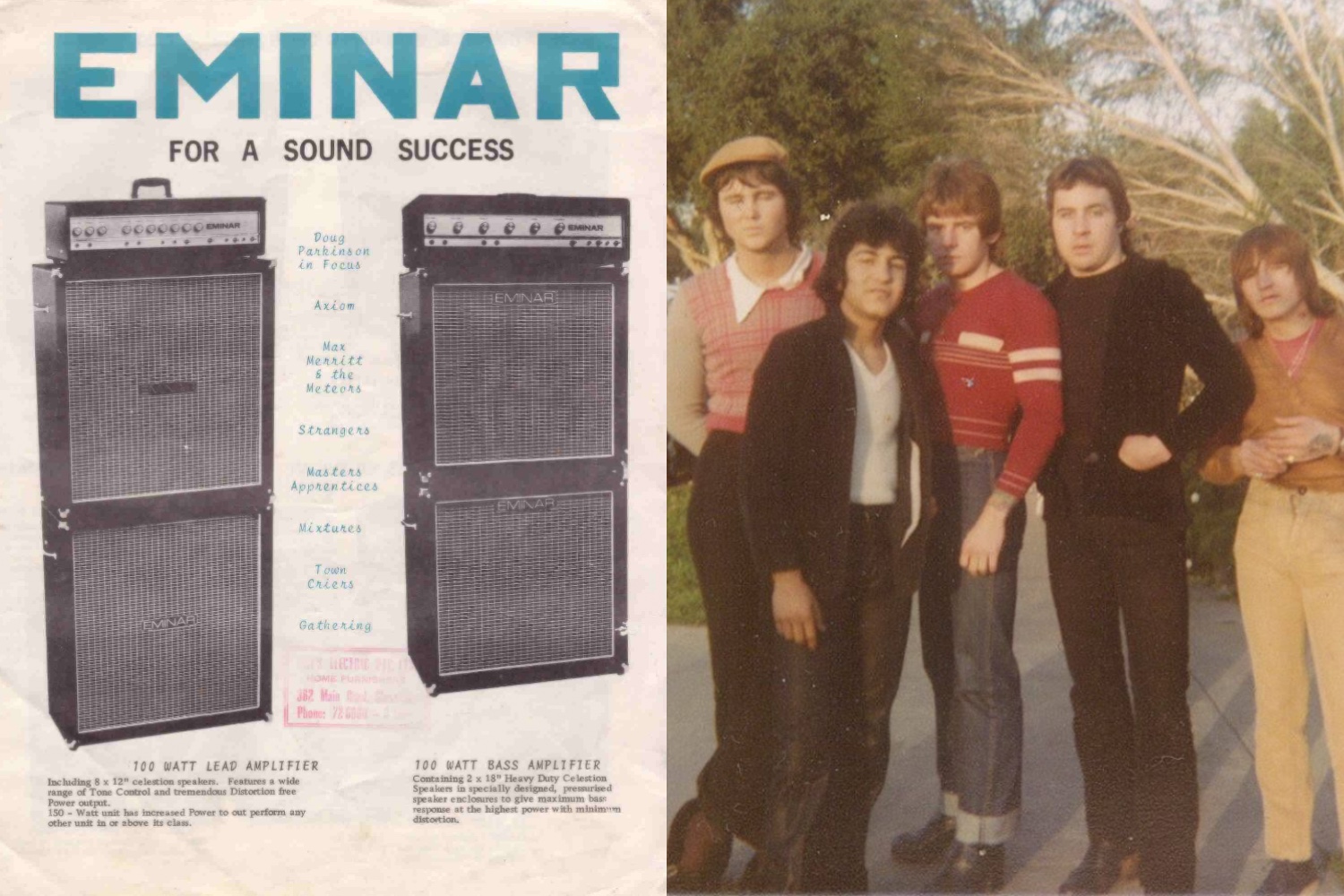

Eminar 150w Piggyback

Without question one of the highest quality purveyors of pure Aussie muscle, Eminar was the brainchild of Gary Millington and Peter Roberts (M&R), two Melbourne musicians who came of age playing in the ultra-competitive band scene that accompanied the first wave of Australian Rock’n’Roll (1956-1962).

Spurred on by a shared interest in electronics, M&R decided to pool their resources, cross-collaborating on various amp and PA projects through the early ’60s, all in the interest of giving their respective bands the technological edge over the competition.

It wasn’t long before the duo expanded their scope to include outside commissions and by the mid ’60s M&R were setting up shop in High St, Northcote, building custom amps and PA systems for the leading bands of the day.

By the time the Sharps were coming into the picture, Eminar had firmly established themselves as a leading name in the local amplifier market, boasting an extensive range of both high and low watt offerings in their ever expanding product line.

Amps like the 150w ‘Piggyback’ were particularly Sharpie adjacent, with their panaromic faceplates and staunch industrial aesthetic striking a chord amongst a working class youth culture keen to bring back the biff.

Sonically, these amps are renowned for their remarkable headroom and massive output, utilising an unorthodox topography capable of ringing out insane SPL numbers from their conservatively listed 150 watts. Employing six EL34 tubes (and with imported Celestion Greenbacks coming stock on all Eminar cabs of this vintage) the Piggyback provided an interesting counterpoint to the grittier, more colourful amps of the day.

They were the decidedly ‘cleaner’ option at a time where grit and colour were very much the hallmarks of a ‘good’ amp. This made the ‘Piggyback’ an awesome pick up for pedal enthusiasts or for thrillseekers eager to push the ‘Piggyback’ into breakup territory: at which point you are probably already deaf.

Also of note is Eminar’s stellar reputation for build quality and ruggedness, a trait that would see the brand exit the ’70s as one of the few Aussie manufacturers left standing, as tariffs were lifted and the Fenders and Marshalls of the world started to make their presence felt in the local market.

And that’s where this particular story ends, as the ’70s gave way to the ’80s and tastes and circumstances changed, so too did the demand for the local amp manufacturer.

Australia was no longer the isolated island nation it once was, and with local buying patterns becoming more and more reliant on imported culture and borrowed history, the Australian amp builder went the way of the T-Rex (the dinosaur, not the band).

The once youthful Sharpie gangs of Melbourne and Sydney also bit the dust, with the primary belligerents having aged out of the very subculture that birthed them, there was little left to do but grow up and move on.

The generation that followed were the working class punks and metalheads of the outer suburbs, but with their splintering of sub-genre and preference for international acts, it was never quite the same.

In the eyes of conservative, mainstream Australia, all of this barely flicked the needle. By 2020, the idea of local manufacturing is almost inherently counter culture, and questions about identity and endemic culture are usually met with either camp irony or visible discomfort.

Thankfully, little sub-plots like the big amp movement offer an interesting case study, a perfect example of the Australian tendency to go full turbo, when (quite literally) left to our own devices.

Rediscover the moments that minted the Australian music festival industry.