From a TB recovery to pioneering synthesisers as we know them today

In a world of endless virtual synths, plugins and samples, a tactile physical synthesiser still holds allure, charm, and – in the case of early iterations such as the Ondioline – manifest fascination.

An incredibly expressive and tonally diverse monophonic instrument, the Ondioline, if you can find one, remains dynamically relevant with tantalising performance potential.

Ondioline synth synthesizer

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

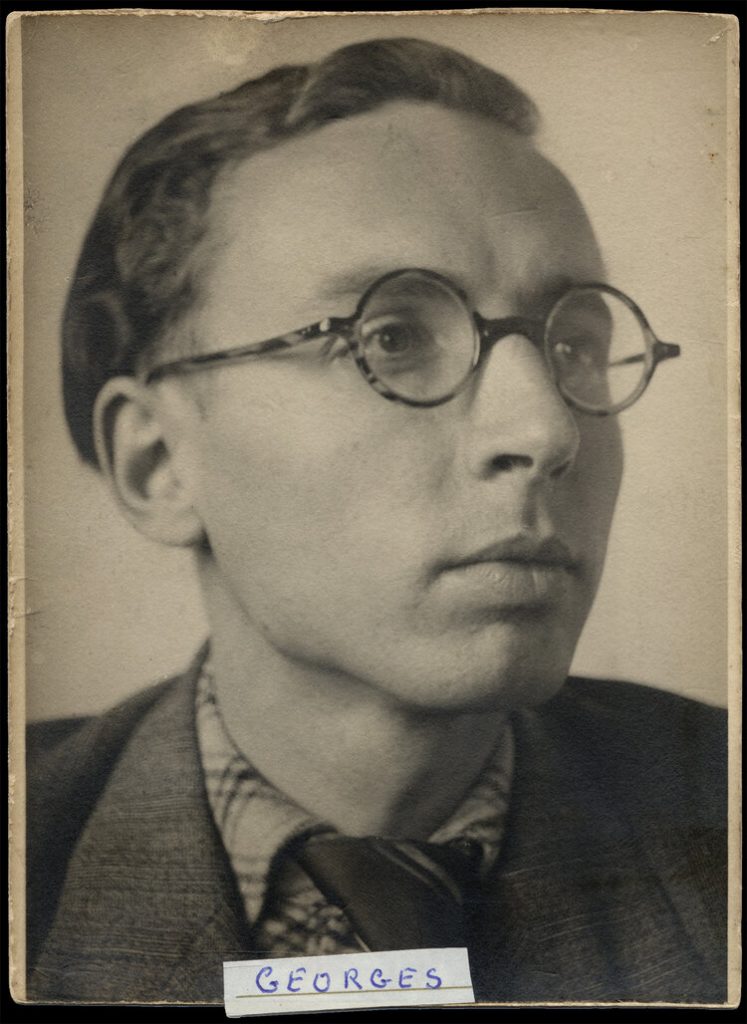

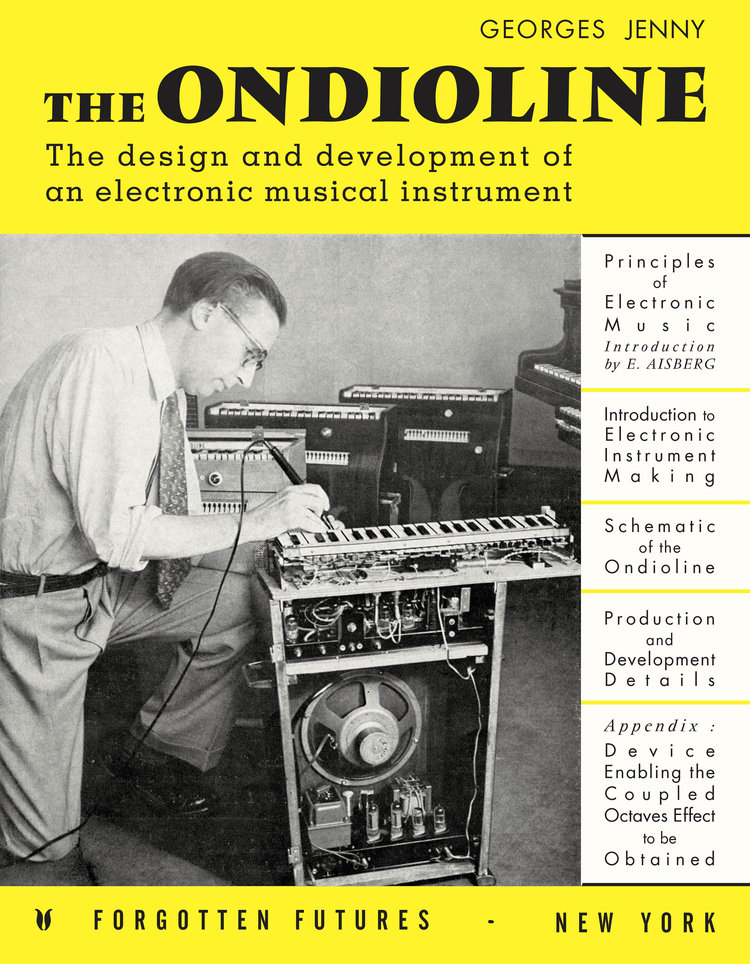

Designed and hand-built by Georges Jenny in the 1940s, the intent was to follow the pipe organ’s manner of replicating various acoustic instruments: flutes, bassoons, horns, bagpipes, oboes, banjos, spinets, clarinets, bongos, cellos, violins etc. Given there were no presets, as per an organ, an accompanying handbook identified which of the many lever combinations could achieve these intended sounds.

Georges Jenny

Up until the late 1960s, Jenny (who passed away in 1975) ended up selling around 1200 of the instruments that he mostly built himself, and encouraged user modification and tinkering by providing the schematics in a book. All of this insight remained available only in French until Gotye’s ‘Forgotten Futures’ non-profit initiative sponsored a much-needed English translation.

French advertisements from the 1950s showcase an astounding violin-like range of performance tones – variations in attack onset and vibrato. Onset dynamics are achieved by striking the keyboard harder or softer, or by using a knee switch on the left to raise volume as a volume pedal might.

The player had the option of using manual vibrato by physically shaking the keyboard, which sits on top of a spring, or by switching on an automatic vibrato, which produces sound more like a modern synth.

A rotary knob on the front allows switching between four registers as a modern mini keyboard controller might, as well as sonically adding four octaves (down to a sub range) underneath the fundamental. This latter feature offers the Ondioline a whisper of polyphonic quality.

There’s also a metallic strip which, when hit, creates electronic percussive sounds. If hit while depressing a note, it will add another dynamic tonal choice into the available palette.

There’s a lot of freedom in an instrument designed to move the air in a room, so while still obviously relying on electricity, there’s much appeal in the custom-built tube amplifier and speaker cabinet the mini keyboard sits atop in being an aesthetically pleasing part of the instrument itself. During the development of the Ondioline, various models existed, with the keyboard sometimes sitting in different positions on top of different shaped amplifiers.

Theremin

The expressive quality of the instrument means it can sound almost theremin-esque, with tonal movement akin to a talk-box or a synth with a wah pedal perhaps.

1960s compositions from artists such as Jean-Jacques Perry used the instrument as a vehicle for quirky French jazz-influenced works or even spaghetti westerns, rather than say, the house/techno/trance or synthwave styles we might associate with synthesisers today.

The Ondioline comfortably sits in a mix alongside acoustic drums, bongos, double bass, piano, and guitars, with an Ondioline (or three) filling the role of a transistor organ such as a Farfisa perhaps. Or even that of an early 20th century-recorded orchestral strings section. But the Ondioline has unique tonal qualities of its own: Perry calling some sounds “Cat” and another “Cartoon”.

There’s so much significance to Perry’s work with the instrument. He is reputed to be the only known Ondioline virtuoso, and became a salesman and representative of the instrument, even appearing on the American TV show I’ve Got a Secret mimicking various instruments on demand. He would tuck the instrument in against the piano, playing it with his right hand and knee, while his left was playing piano accompaniment.

The gifted musician’s compositions entertainingly explore the range of the instrument. His quirky French-cinema style has the instrument stuttering, whistling, meowing, and dancing around like a bassoon.

The Ondioline has to be heard to be believed. It’s incredible not only for the era in which it was created, but is still tantalisingly inspiring, offering a unique sonic pallet to create with.

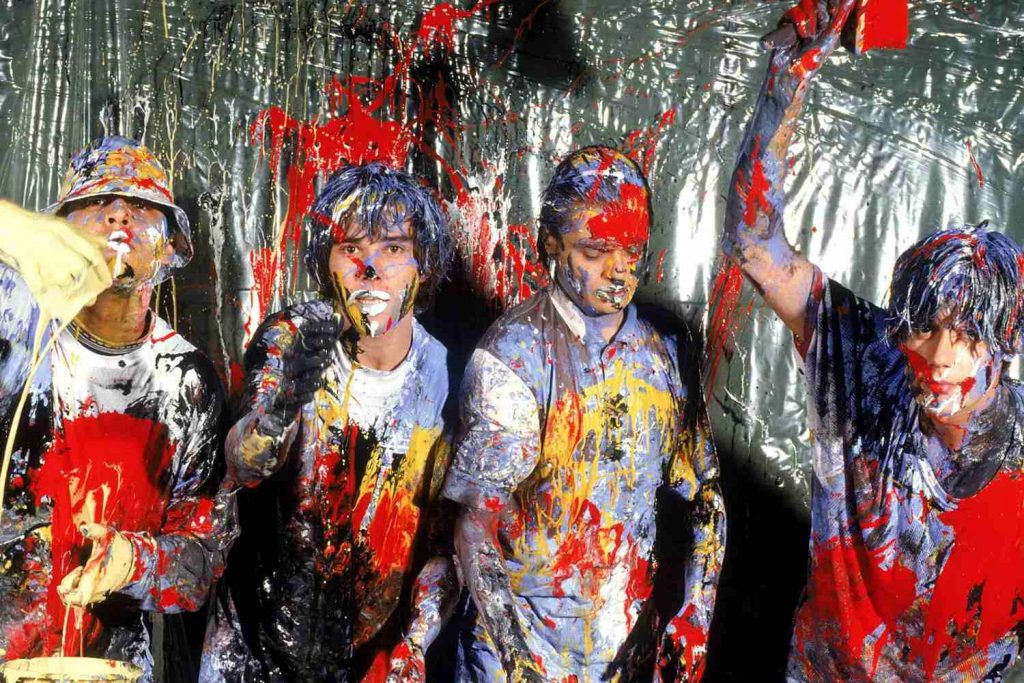

Listening to Perry’s work on the instrument, one can understand why Gotye has become so enamoured with it. Devoting time and money to initially acquire a very damaged one (purchased sight unseen!) and then to have it restored, Gotye embarked on a whole new venture – Forgotten Futures – to promote the exceptional marvels of the little-known Ondioline.

The smile-inducing sonic possibilities and the way it sits so comfortably amid acoustic instruments make it seem like a perfect Gotye instrument when considering his existing body of work.

Not long after Perry passed away in November 2016, Gotye’s ‘Ondioline Orchestra’ was formed, with a single ‘Cigale’ released in 2017 (in honour of Perry and sitting comfortably next to Perry’s work), and at least one live performance in 2018.

Gotye’s provision of the English translation of the schematics book is an important perpetuation of Jenny’s culture of encouraging users to physically dabble with their instruments, as it’s meant others can now technically understand and restore instruments themselves. Technicians such as Stephen Masucci and Daniel Kitzig have restored numerous Ondiolines, and Forgotten Futures are even recreating spare parts.

Forgotten Futures is an apt name indeed for a team giving a wonderful instrument from the past such a hopeful and inspired future.

Head to the Ondioline website for more information. For more Gotye and Ondioline action, check out this piece from the New Yorker.