The South African music industry underwent a massive change when Nelson Mandela became the first democratically elected president in 1994, and the political and economic sanctions that had been placed on the country under apartheid rule were lifted. Kwaito grew out of the township of Soweto, and married slowed down house beats with melodic rapped vocals and heavy bass lines. The name itself is derived from the Afrikaans word kwaito, meaning hot tempered or vicious, and while the lyrics were initially in Tsotsitaal, they expanded to include a mixture of English, Zulu, Sesotho and the South African street slang Isicamtho, amongst other indigenous languages.

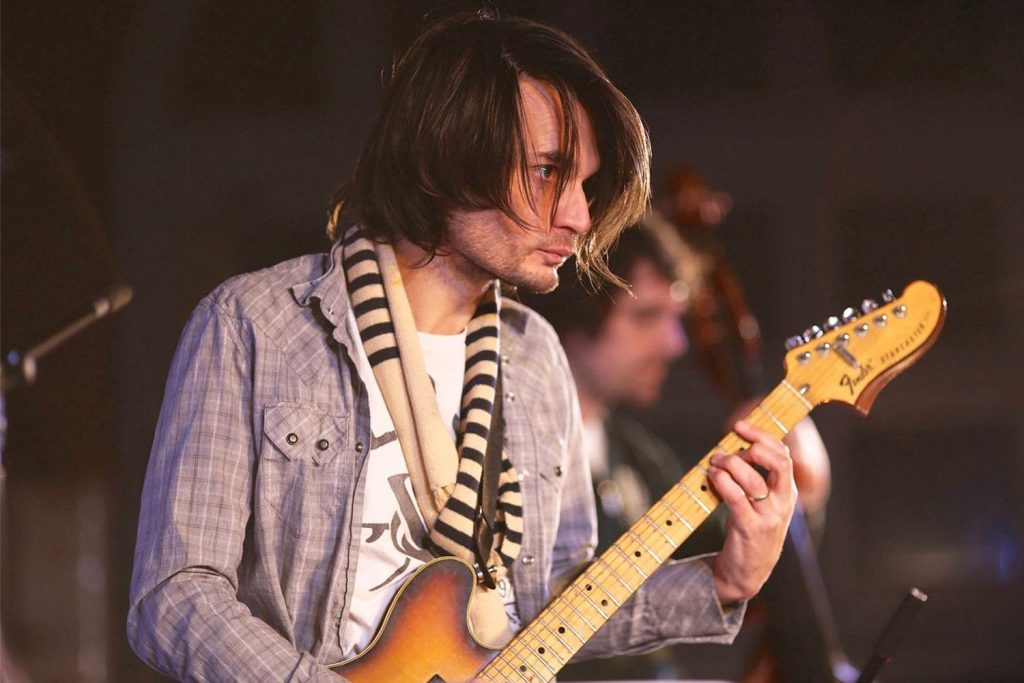

Though house music had existed in South Africa for several years, it wasn’t until the sanctions were lifted that people had greater access to international musical styles, and by this time their version of house had been adapted to suit the taste of the Johannesburg youth. Two house DJs from the area named Oscar Mdlongwa, known as Oskido, and Christos Katsaitis are credited with being amongst the first to slow down the tempo to around 110bpm and introduce lyrics that reflected township life. “After we slowed down the beats we started thinking, ‘Why can’t we put our own lyrics on it? Why can’t we write, we are free now,” said Oskido to The Guardian.

Oskido

The production values were decidedly simple and part of its initial popularity certainly rested in the fact that musicians with little resources could adapt pre-existing house beats to create new tracks and then perform them without owning any instruments. The music grew to include several rhythmic and melodic variations that borrowed from the country’s past, including 1920s marabi, ‘50s kwela, ‘80s bubblegum and imibongo, a traditional form of African spiritual poetry.

Though the songs spoke of local life in the townships, the music soon grew criticism for featuring overly sexualised and misogynistic lyrics that placed an emphasis on glamour and consumerism over substance. The heroes of the previous generation of South African music, such as Miriam Makeba, Brenda Fassie and Hugh Masekela, had been overtly political, and by making this new music purposefully apolitical in a time of such major national change, the young musicians were making a distinct break from the past. Like gangster rap in the USA, this in itself was a defiantly political act, declaring for themselves what the first generation outside of apartheid were all about.

“After the release of Nelson Mandela we were tired of singing these political songs,” said Oskido. “I think we just came up with this idea of talking about things in a way that can relay the message via a dance culture.”

However, in 1995 Arthur Mafokate had the first major kwaito hit with his song ‘Kaffir’, the word being an ethnic slur used against black people, with the main hook repeating the refrain, ‘Don’t call me a kaffir’. Not only was the song highly controversial, with critics claiming it was spreading hate speech and being banned from some radio stations, the song was embraced as a message of empowerment by kwaito fans.

According to Oskido, he was called into a meeting with Mandela who was concerned about the message that kwaito was spreading at such a sensitive time for the country. In 1997, Oskido’s group Brothers of Peace (BOC) put a call out to several well established jazz legends to collaborate on their Zabalaza album, which resulted in contributions from the late pianist Moses Taiwa Molelekwa and Masekela, and led to the group being signed by US production team Masters At Work.

This was not a token gesture from Masekela, who would go onto record his own interpretation of kwaito on the 2005 album, Revival. “Kwaito is going to be around for a long time,” he wrote in the album’s liner notes. “It’s going to become part of mainstream music. I find nuances in it that so-called critics will never understand. It’s the core of township feeling.”

A 2003 article in Brand South Africa reported that, with a population of over 40 million, half of whom were under 21 years old and 75% of whom were black, youth culture exerted a major influence over not only popular culture but national identity.

Dancehall: From Slave Ship to Ghetto, a book by Sonjah Nadine Stanley-Niaah, estimates that 30 per cent of the hit records in South Africa between 1999 and 2004 were by kwaito artists, though other sources report that for a few years its sales were only second to gospel.

Mandoza

Mandoza became one of kwaito’s first crossover superstars, with the release of his 2000 album Nkalakatha, which not only played with the tempo but also introduced elements of American commercial R&B and hip hop. However, sales began to decline as a more internationally minded version of house music, such as that played by South Africa’s most famous DJ, Black Coffee, became increasingly popular. By the mid-2000s kwaito realigned itself with these trends by speeding up the tempo that once helped differentiate it, resulting in a more industrial house blend that purists claimed watered down the sound and symbolism.

Today kwaito continues to evolve as a new generation of South African artists reinterpret and repurpose it; however, the genre will forever by linked to the anger, defiance and revolutionary spirit that came out of the townships in the 1990s.