"I've always been obsessed with drums. They fascinate me." - John Bonham

John Bonham continued, saying “Any other instrument – nothing. I play acoustic guitar a bit. But it’s always been drums first and foremost.”

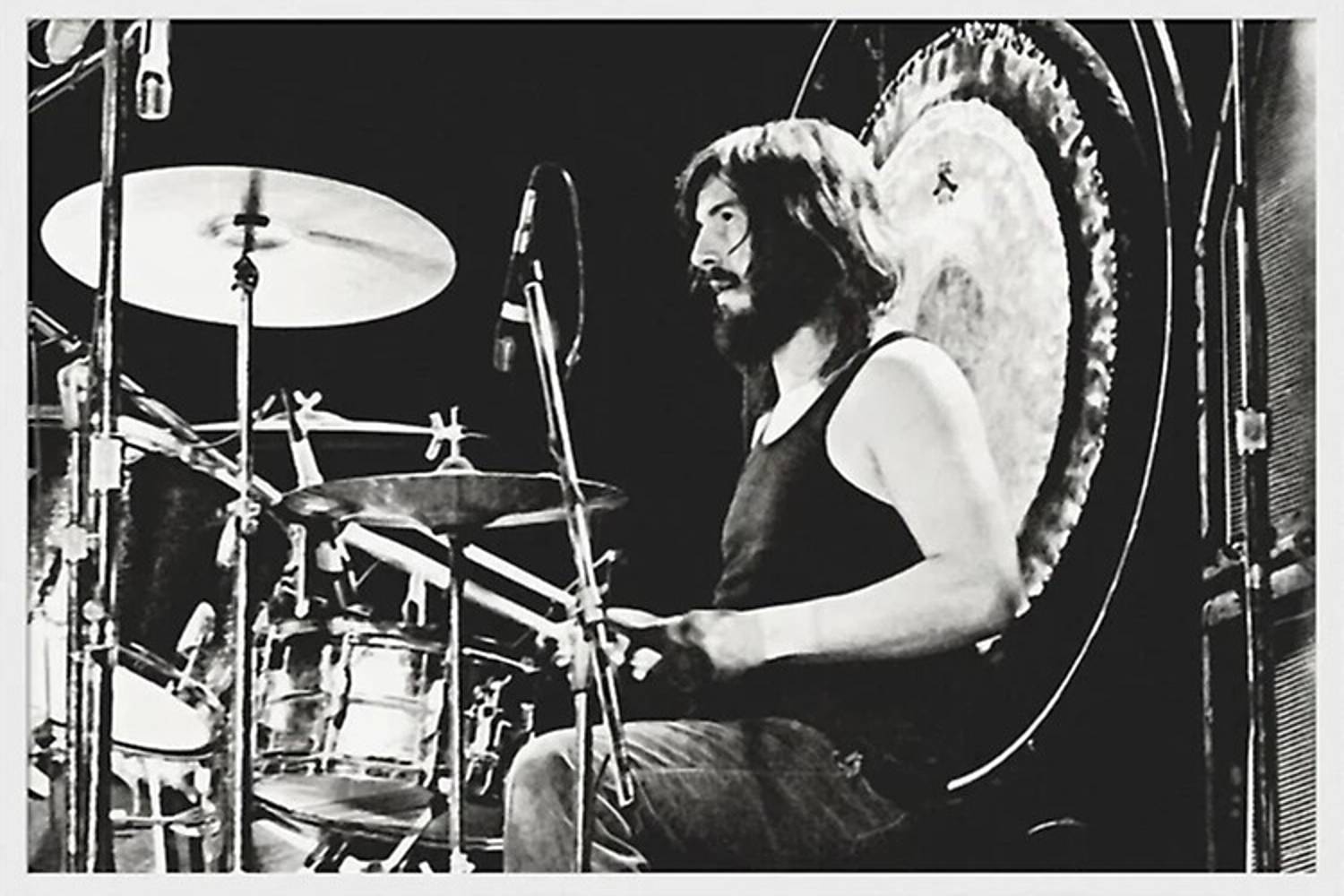

John Bonham

“I don’t reckon on this Jack-of-all-trades thing. I think that feeling is a lot more important than technique.

“It’s all very well doing a triple paradiddle – but who’s going to know you’ve done it?

“If you play technically you sound like everybody else. It’s being original that counts.”

Read all the latest features, lists and columns here.

Birmingham

John Henry “Bonzo” Bonham was part of the early Birmingham sound in the 1960s, when colleagues like Cozy Powell, Bill Ward of Black Sabbath and Bev Bevan of The Move/ELO went for a loud sound.

Ward recalled: “Bonham was an inspiration when playing half-time blues. His grooves were always in the sweet spot.

“He filled the emptiness between the fours of the snare with triplets and polyrhythms, astonishing the listener and gathering delighted applause for each splendid execution of what seemed the impossible.”

Most Imitated

One of the most imitated and respected drummers of our time, Bonham died at the age of 32, officially on September 25, 1980.

He could be an arch raver destroying hotel rooms and riding a Harley Davidson bike down the corridors of a five-star hotel to living on a farm with his family and collection of vintage hot rods and bikes, to being a ferocious human who admitted he suffered from stage nerves.

It was the depression he felt at leaving his children behind to go on a world tour, which led to a fatal 40-vodka binge.

On December 4, the band issued a statement that they were breaking up. It was a testament to their knowledge he was indispensable to them.

Led Zeppelin had been rehearsing for the world tour, to start that October in the United States.

The band had contacted Australian promoters about a return visit.

John Bonham left a tremendous legacy behind. One wonders in which awesome ways he (or come to think of it, Zeppelin as a band) would have developed if he had lived.

Meantime if you want to capture his sound, here are 12 tips.

1. HIS BASS DRUM IS BIGGER THAN YOURS

Bonham went for large bass drums (26” x 14”) because of his swing/jazz hero Buddy Rich.

It wasn’t always his size. Led Zeppelin 1 was made with a Slingerland, a present from the Yardbirds’ drummer when they broke up in 1968.

The kit Bonham took on Zeppelin’s first US tour in December 1968 was a 22″ x 13” bass, two 16″ x 16” toms, a 13” x 9” kick, a 14″ x 5” Ludwig chrome snare, a ride, two crashes and 14″ hats.

They were opening for Vanilla Fudge, and its drummer Carmine Appice and Bonzo stuck up a bromance, getting him a Ludwig sponsorship.

Oversized

“When he saw my two 26″ maple bass drums, oversized toms, and deep snare, he wanted the same, Appice related.

“I called Ludwig: ’I think this band is going to be really big.’ How’s that for an understatement!

“They gave him the same setup as mine, complete with gong. He loved it.”

One of Bonham’s drum techs in the late ‘70s, Jeff Ocheltree, said in a YouTube workshop “The batter side and the resonance side was pitched higher than one would think.”

Amount Of Air

This was because the size of the drums, a large amount of air had to move quickly through the shell “and get a round full sound.

“That was the secret of his great sound, the fact that the heads were tuned up a lot higher on the bottom than they were on the batter side and that gave the whole total sound of the drum on the impact with the stick.”

2. BE “BRIGHT AND POWERFUL”

Bonham: “I’ve always liked drums to be bright and powerful. I’ve never used cymbals much. I use them to crash into a solo and out of it, but basically I prefer the actual drum sound.”

“I really like to yell out when I’m playing. I yell like a bear to give it a boost. I like our act to be like a thunderstorm.”

3. GO BACK TO HIS HEROES

He might have changed hard rock. But a lot of John Henry’s Zep work were inspired by the jazz, swing and big band skinsmen he grew up idolising, as Buddy Rich, Max Roach and Gene Krupa.

The idea of playing with his hands came straight from Papa Jo and Joe Morello.

He even incorporates swing influences on that archetypal metal anthem “Whole Lotta Love” which allows him to drive the song and push the other three to perform to greater heights.

Just before his solo on “Moby Dick”, he’d shout out “the drum also waltzes!”, referencing a Max Roach track from 1966.

Impact

Also having an impact were Motown, R&B and soul players he heard as a teenager – like Clyde Stubblefield and Bernard Purdie) and whom he investigated further on Zep’s frequent US tours.

The opening to “Rock And Roll” is an out-and-out tribute to Charles Connor’s intro to Little Richard’s “You Keep A-Knockin’” (1956) while “Black Dog” incorporates many funk and Motown syncopations.

4. DOUBLE PLY COATED BATTER HEAD

Bonzo liked the double-ply batter head, tuned to medium pitch. He placed a felt strip under the head near where the head would hit.

For the res, he’d use a single-ply head with an inner plastic muffling ring, tuned higher than the batter head (most likely between a half step and a fourth), using an old bass head cut up to save money.

5. SIGNATURE TRIPLETS & LEFT DOWNBEATS

Put simply, a musical triplet allows the player to play three notes in the time of two notes.

It was a Bonham signature and done so quickly some assumed he was using double pedals.

Actually he only used a standard bass drum pedal, putting a toe first and then followed by a leg, giving the second stroke a louder sound.

The idea of playing six notes in the place of four, came from Rich, Krupa and Roach.

Best Examples

Experts have suggested that Bonham’s best versions of this move were in “Kashmir” from the self-titled live DVD and “Since I’ve Been Loving You” from How The West Was Won, where he accentuated the third and final on the kick, or just the left hand notes.

Another signature Bonham move was to skip the normal drummer approach of stressing the right hand with the right foot on the downbeat.

Instead, as one Bonhamophile explained, he would sometimes “enjoyed playing his kick on the upbeats of a phrase while his left foot held the downbeat.”

You start with the hi-hat, on the upstroke bring the kick in, with the floor hat echoing the same beat as the hi-hat.

The first snare shot lands on the downbeat, same as the floor tom and the hi-hat. The next share is on the upbeat and ends on the kick.

It is a difficult one, but Bonzo liked it because it provided more textures as on “Four Sticks”, and made him sound he was playing more drums than he really was.

6. DON’T JUST MAUL, BE LEARNED

Sabbath’s Bill Ward said Bonham’s talent lay in his being a natural and a very learned student.

“Behind his almost brutish and chaotic appearance he was an endearing man, studious, and a hopelessly caught-up-in-drums-and-drummers man,” Ward told Bonham From The Perspective Of His Peers 2.

“His knowledge of drumming was overflowing. This was the Bonham I knew.”

Bonham himself said, “I never had any lessons. When I first started playing I used to read music.

“I was very interested in music. But when I started playing in groups I did a silly thing and dropped it. It’s great if you can write things down.”

7. TAKING THE MIKING

The secret of capturing Bonzo’s thunder on record was how the engineers miked him.

Glyn Johns accidentally found the best way to capture Bonzo when working on the first Zep album in 1969.

While directing four mics from the middle of the stereo mix, he unintentionally directed one of them to one side – and got the result he wanted. For the kick drum, try the Shure Beta 52.

New Approach

Brother and Led Zeppelin IV engineer Andy Johns tried a new approach on “When The Levee Breaks”, one of the greatest drum sounds in rock history.

They were recorded at the bottom of a staircase of the Headley Grange manor, with two Beyerdynamic M 160 strung up a stairwell from the floor above.

This was passed on to a pair of Helios F760 compressor/limiters set aggressively to obtain a breathing effect.

A Binson Echorec, a delay effects unit, was also used.

Thunderous

The thunderous sound accentuated Bonzo’s impeccable use of hi-hat, kick, and snare to denote the fear and menace of the impending flood sung about in the song.

Some years back, Mixdown and Abbey Road Institute posted a session on recreating the track’s drum sound.

Another engineer, Eddie Kramer, reckoned technology was not that important with Bonham.

It was about his muscles, technique, and instinct for when to swing, be blues gentle, or just be mean’n’ murderous.

Thing About Bonham

“Here’s the thing about Bonham,” Kramer explained in the Ask Eddie Kramer series on Gibson TV.

“If you put him in the room and you only had three microphones [of any level of quality], you could record John Bonham.

“The way he hit the damn drums and the way he tuned the kit …That combination is the sound. Watching him play … the contact was so fast and had so much impact.”

Live, Bonzo preferred a pair of Shure PGA181s, one directly over the snare, and the other 6” above the floor tom and to the side.

Mics

In the book BONZO: 30 Rock Drummers Remember the Legendary John Bonham, Anthrax’s Charlie Benante noted that while John Henry didn’t use too many in the studio, “the mics that he did use were placed in a certain way that when he heard it back, it sounded exactly how he heard it when he sat there.

“So, sometimes when you hear drums mixed on a record, they may sound like a little disproportionate type of thing, because the toms don’t sound as equal as the snare or kick.

“But with him, everything was mixed really well and compressed, so the triplets always came out sounding correct. And he was totally on top of that.”

8. KEEP IT SIMPLE

The success of Ringo Starr and Charlie Watts relied on their playing the band, not playing the drums.

The simplicity of something like “Kashmir” or “When The Levee Breaks”, keeping the boat steady while all around were intricate musical overplays, showed that Bonzo didn’t have to prove himself to anybody.

9. USING YOUR HANDS

Quote: “I can get an absolutely true sound. It hurts at first, but the skin soon hardens and now I can hit a drum harder with my hands than with drum sticks.”

10. STATUS CYMBALS

John Bonham was a Paiste man, first with the Giant Beat (which consisted of a bronze alloy (B8) and a smaller tin content than Zildjian’s (B20) range.

Then came the 2002 Series which launched in 1971, around the time he became a Paiste endorsee, and which he mostly used (although he was still using some Giant Beats on the early tours) with a preference for aluminium cymbals.

He occasionally used the 600 and 3000 series, specially the 20 Formula 602 Classic Medium Ride from 1978 on.

Bright Enough

Bonzo was drawn to the Paistes as they were bright enough to be heard over the Zeppelin sound, and tough enough to withstand his hammer.

A typical Bonham cymbal setup would include:

- 24” 2002 series ride

- 15” 2002 series Sound Edge hi-hats

- 16” or 18” 2002 series crash on his left

- 18” 2002 series medium ride for crashing on his right

According to Paiste, he would sometimes also use an 18” crash on his left and a large 22” or 24” crash/ride on his right, all from the 2002 series, and whose heights he would keep changing.

Arsenal

To capture his sound, your arsenal would also include a 14” or 15” hi-hat, a ching-ring (headless tambourine), that famous Ludwig cowbell from the early ‘60s which are these days difficult to get, and a pair of timpanis (Ludwig Universal Model copper-shelled) ranging from 20” to 32” inch.

Alternatively try timables or Natal congas because Bonzo used those before switching.

Eventually he added three gongs (also inspired by Carmine Appice) in various diameters (29”, 36” and 38”) in hammered brass initially with two painted Chinese characters (latter changed to Paiste) to the front, top of rim with two suspension holes.

Bonham would warm up the gong with a mallet, using it for percussive effects as well as a whack-out. He’d set them on fire midway through Zep’s set.

Gongs

Don’t even think of getting one of these gongs unless you’ve landed an inheritance.

In 2009, a 36” symphonic gong used at the London Royal Albert Hall on January 9, 1970, sold for US $64,660 (AU $98,620).

11. USING THE WRIST

“It was all in his wrists,” said Charlie Benante of Anthrax.

Bill Ward of Black Sabbath offered: “Bonham was light of foot and light in his wrists.

“It was his dexterity, his touch that seemed to intuitively know how to find the power points on each drum.”

Jimmy Page put on his producer’s hat when discussing why Bonham was a dream to record.

Marvellous

“One of the marvellous things about John Bonham which made things very easy was that he really knew how to tune his drums, and I tell you what, that was pretty rare in drummers in those days.

“He really knew how to make the instrument sing, and because of that, he could just get so much volume out of it by just playing with his wrists.

“It was just an astonishing technique that was sort of pretty holistic if you know what I mean.”

If you look at video footage and photos of Bonzo in full flight on stage, he never flails above his head.

By keeping his hands low, usually level with the rims, he could conserve his energy. By using the power in his wrists, he’d whack down with such ferocity that the drums would resonate fully.

12. TOMS AND SNARES

John Bonham used two or three toms, usually a 14” rack + 16” or 18” floor toms, with which to get those awesome fills.

The single-ply resonant heads double-ply batter heads would be both tuned to medium and roughly a third apart.

Let the size of the tom decide the tuning.

For a snare, most recommended is a Ludwig LM402 Supraphonic 6.5” x 14”, aluminium (“never chrome or brass” for Bonzo, said his tech Ocheltree) although others have said steel or brass are close enough.

Resonance

Keep the resonance by not fitting it too high, and best mic would be a Shure SM57.

The batter head should be higher than the normal “standard”, and the reso head a fourth higher than that.

“The snare drum tuning was an important part of the John Bonham sound,” according to Ocheltree.

“He understood the dynamics in the snare sound and the batter sound, in that he pitched the snare sound way up and he never choked the snares.

“He loosened the snares just enough so you get the sensitivity of the snares but you’d also get wholeness of the drum from top to bottom.”

Keep reading about Glyn Johns here.