A deep dive into the techniques used to write and record some of the most iconic ABBA songs.

You’d be hard pressed to find a group as original as ABBA. With decades of widely popular albums and musicals under their belts, they’ve garnered plenty of fans across the globe. ABBA songs are defined by the combination of their unique harmonies and feel good songwriting, but perhaps most importantly, showcase their original production and recording processes.

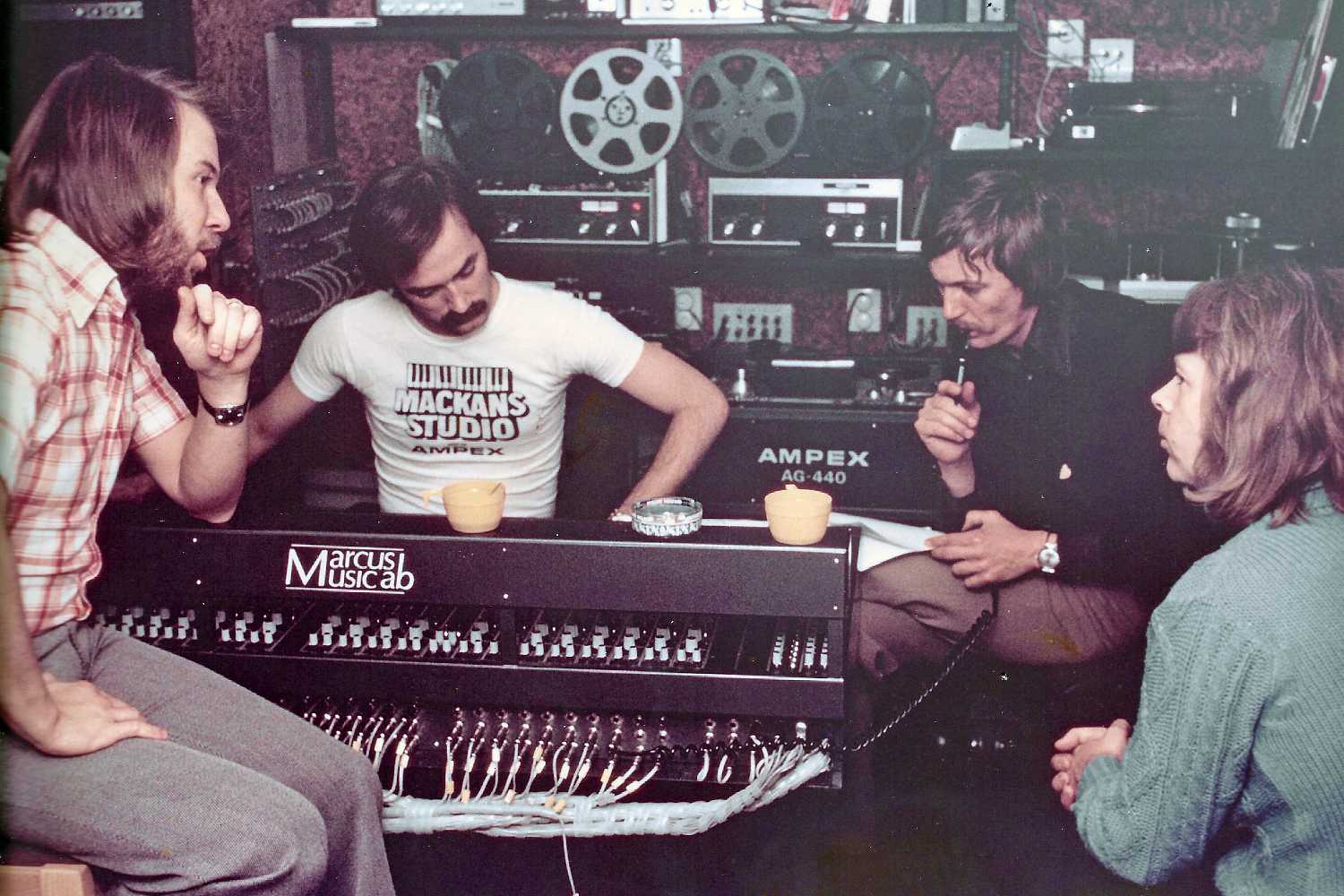

These processes are widely regarded as some of the best and ABBA’s long-time producer Michael B Tretow’s unique approach to the recording process helped the Swedish four-piece achieve stardom. There’s a lot to creating an ABBA song. Using a selection of rare and sophisticated gear, Michael, along with Bjorn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson worked tirelessly to make each track an experience.

Read up on all the latest interviews, features and columns here.

The trio often recorded each element of any given song separately. Channels were gained up and pitch shifted after the fact, resulting in that unique sparkle many have tried to replicate.

Starting with the most distinct element of any ABBA piece, the pristine and expertly mixed vocals. Many fans have gravitated towards vocalists Frida and Agnetha’s unparalleled cohesiveness, and the fact that they flowed together like one voice. This was thanks to track isolation and pitch shifting, but also due to the use of their boutique and highly sought after Harrison 5632 console.

Their longtime drummer Ola Brunkert’s performances were often recorded in a drum booth, in isolation from the rest of the band. Michael noted in an interview at the time that they sought out the dryness the booth holds.

ABBA songs

A number of ABBA tracks were produced by Tretow; ‘Ring-Ring’, ‘Waterloo’, and ‘Super Trouper’, among many others, but something that’s common through those tracks is the tom heavy drum mixing. To not overpower the light and quaint vocal lines, Michael would only mic the toms and bass drums, believing that the cymbals overpower the rest of the arrangement. Due to his eversion to cymbal heavy music, he’d chuck AKG-C414 condenser mics on the drums, perfect for picking up the lower sounds ruminating from Brunkert’s kit.

The guitars (bass and electric) would be next in Michael’s process, recording Benny, Bjorn’s and bassist Rutgar Gunnarson’s guitar lines in their own room—a storage room or add-on—anything that could house an amp and guitar player. The amp would be pumped up to 11, with sound filling the room. The amp was miced, and a mic was placed outside the room, both picking up every little slide, bend and strum. Once again, this unique process gives the guitar lines their own flare and individuality which can be heard throughout much of ABBA’s discography.

A commonality through much of ABBA’s music—from ballads to rock—is the piano. Michael would capture the grand piano with three C414 condensers, which seems to have been one of his favourite mics.

The idea of using three mics to record a piano was not so common at the time and Michael became one of the first engineers to do so. The piano lines throughout ABBA’s music are some of the most iconic and the layering of these three lines giving a flare to songs like ‘Mamma Mia’, ’S.O.S’, and ‘Ring Ring’. The middle line was fed through a MXR flanger, which was then run through a bucket brigade delay—allowing for a sort of automatic pitch shift that the group seems to love so much.

Another main element of any ABBA track is the synth lines, and it was the Polymoog that gave their music that distinct electronic vibe. In an interview with Sound International Magazine in 1980, Michael outlined the Polymoog recording process for ‘Arrival’ saying “the Moog was picked up by two ambient mics only. To get a ‘natural’ sound, as if it were a bunch of real instruments playing out in the studio, I moved the amp in the room for every overdub we made, and recorded each harmony in stereo on two tracks. If you listen to the record it’s very hard to tell what instrument it is; it sounds like all-metal bagpipes – or something.”

It’s clear through, a lot of the engineering behind recording the fullness of ABBA is brought through by a lot of ambience. Mics were placed in various spots throughout recording to catch room noises the main mics didn’t pick up. This broadens the room feel of their tracks and helps gives a lot of their music that distinct orchestral feel.

Then after the long, and at times tedious process of recording, re-recording and overdubbing instruments, it comes time for mixing. The mixdown process starts with the Michael putting together a basic mix, with Benny and Bjorn mixing their own versions. Then they’re all put together, and an ABBA song is created.

A number of ABBA’s releases have been put together at their studio; Polar, which is equipped with a rare Harrison Mixer and Universal Audio LN 176 valve limiting amplifiers, the latter of which is yet another integral facet of the ABBA sound and a precursor to the legendary 1176! Michael used these compressors on all the instrument tracks, which helped normalise the volume of each track and add to the depth throughout their music.

The last time Michael worked on an ABBA release was 1981’s The Visitors, then after suffering a stroke in 2001, retired from public life.

Modern ABBA music has been notably less common, the group disbanding after their last album, having reformed at various points to work on the popular Mamma Mia film series, and have come together for an upcoming album titled Voyage.

21st century ABBA has had engineer Bernard Löhr at the helm, working alongside Benny and Bjorn for production of modern ABBA, not wanting to replicate their sound in the ’70s but give it a modern spin. In an interview with Sound on Sound, Löhr outlined his differing approach on the track ‘When I Kissed The Teacher’ from the second Mamma Mia film. The song holding a whopping 84 tracks, clearly following Tretow’s ‘Wall of Sound’ mentality.

The engineering process for this recent release was very clean, with plugin use sparse. The Waves SSL G-Channel plugin was one of the only changes to their original setup and it was used on some of the backing vocal lines and 10 drum tracks, providing some mid-range punch, and some of the dryness that was integral in early ABBA work.

As you can see, there was quite a lot that went into ABBA’s music production process, which is one of their reasons their tracks still stand out to this day. Maybe next time you’re in the studio you could utilise a few of these tricks for your mixes.

Keep up to date with all things ABBA here.