Tracing stompboxes from the early routes up to their rise to prominence in the '70s.

There was a time not long ago, before guitar effect pedals, when effects were strictly a studio tool, the result of experimentations by engineers and musicians, such as Les Paul, who began to create echo effects by manipulating reel-to-reel tape.

Once guitars became amplified in order to be heard above the big bands of the 1930s, manufacturers began to look at ways to add further expression to the instruments.

Today, we’re gonna take a deep dive into the origins of guitar effects pedals and how they became the standard for guitar players the world over.

Summary:

- The first guitar effect pedals was created by DeArmond and was a Volume pedal, followed by a tremolo pedal but they weren’t suitable for stage use.

- Gibson produced the first distortion pedal in the ’60s which was popularised by The Rolling Stone guitarist Keith Richards on ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’.

- The Wah pedal was created by a twenty year old engineer by accident, which birthed the legendary Cry Baby guitar pedal.

Read all the latest features, columns and more here.

An example of this added instrument expression was the Rickenbacker Electro Vibrola Spanish guitar that was produced between 1938 and 1942, and featured a built-in motor that moved the bridge in order to create a vibrato effect.

Trem-Trol Model 60 or 60A

Not long after, Rowe Industries created the DeArmond Model 600 Volume Pedal, followed in 1941 by the DeArmond Model 601 Tremolo Control, also known as the Trem-Trol, Model 60 or 60A. When it launched commercially in 1946 it was the first in a now huge number of standalone guitar effect pedals on the market.

The unit created a tremolo effect by running a signal through a water-based electrolytic fluid, with an electric motor driving a spindle that moved up and down to create fluctuations in the signal, resulting in volume modulation. It had two controls— increase and speed—and found an early adopter in Bo Diddley, who used it on his 1955 number one hit ‘Bo Diddley’, thus changing the rhythm of rock ‘n roll forever.

Such early pedals were not extremely practical for stage use as they were fragile, bulky, and expensive; however, when transistors became widely available in the 1960s it meant that pedals could become lighter and more affordable.

Gibson Maestro Fuzz-Tone

In 1962 came the world’s first distortion pedal—the Gibson Maestro Fuzz-Tone, which retailed at $40 (US). The pedal was based on a circuit designed by Nashville studio engineers Glenn Snoddy and Revis Hobbs, who had been trying to emulate a sound that Snoddy happened upon by accident when an output transistor in a console caused a bass signal to distort, whilst recording the 1961 country ballad ‘Don’t Worry’ by Marty Robbins.

However, Gibson marketed the pedal as being designed to alter the tone of guitars and basses in order to emulate the sound of different types of instruments, such as brass. Although they produced 5000 units in 1962, sales were not good until Keith Richards used a Fuzz-Tone on The Rolling Stones’ ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’ in 1965, after which the pedal’s sound became highly in demand. Ironically, Richards has stated that he was in fact attempting to recreate the sound of a horn line on the song’s iconic riff.

FZ-1A Fuzz-Tone

To meet the sudden demand, Gibson released the FZ-1A Fuzz-Tone and moved an estimated 40,000 pedals in late 1965, and several other companies quickly released similar models, such as the Burns Buzzaround, Macaris Tone Bender, the Electro-Harmonix LPB-1, which later became the Big Muff Pi, and the Arbiter Fuzz Face, which was used by Jimi Hendrix on Are You Experienced in 1967.

At the same time another major invention was hit upon almost by accident. The all conquering success of The Beatles meant that the Vox amplifiers they famously used had become extremely popular in America, and consequently the UK company who made them, Jennings Musical Industries, needed a US distributor. Striking a deal with the Thomas Organ Company in LA, the shipping costs were soon found to be too prohibitive, leading to Thomas Organ actually buying the rights to manufacture Vox locally.

CryBaby Wah

Brad Plunkett, a then 20-year old engineer, was charged with the task of finding a way to make the amplifiers cheaper to produce, and in attempting to replace a mid-boost switch with a cheaper potentiometer, he found that turning the pot created a strange pitch fluctuation. Realising he was onto something, Plunkett took a volume pedal from a Vox Continental organ and replaced its workings with the pot and a 9-volt battery. Pressing the pedal down accentuated the lower frequencies and raised the highs, resulting in a harmonica-like ‘wah’ sound.

The Thomas Organ Company employed the Vox Ampliphonic Orchestra to demonstrate their products for marketing purposes, and the group’s guitarist, Del Casher, made one such recording using the pedal, named the Cry Baby, to be distributed to instrument stores in 1967.

This caught the attention of Frank Zappa who hired Casher to play in his band, and in turn is said to have introduced the pedal to Jimi Hendrix, who would use it on ‘All Along the Watchtower’, ‘Voodoo Child (Slight Return)’ and more. Unfortunately for Thomas Organ, nobody registered a trademark on the unit’s name and in 1966 Dunlop released their own Cry Baby, which became very popular and helped to dominate the sound of funk and disco in the 1970s.

With guitar effect pedals becoming their own industry, several companies were formed in the 1970s to address the market, including the formation of Roland’s BOSS subsidiary in 1973. The company began to manufacture compact pedals in 1977, releasing the classic DS-1 distortion pedal the following year.

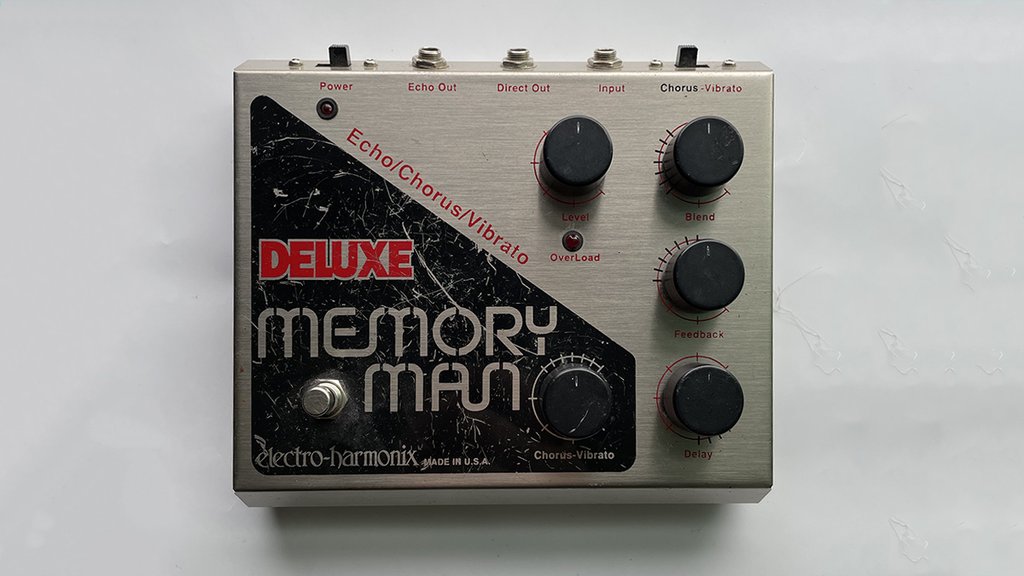

Electro-Harmonix Memory Man

In 1976 Electro-Harmonix released the first of their Memory Man echo/delay units, the Solid-State Echo/Analog Delay Line. The idea was to recreate what had previously only been possible in the studio by manipulating tape, and utilised a bucket brigade delay integrated circuit, which passes the signal through several stages, each creating a signal delay before the output.

The pedal was a watershed moment, allowing guitarists to affordably and easily achieve and control delay onstage. After this, pedals went wah-wah, with them basically every guitarist having at least one in their setup, not to mention the chains commonly found today. For that, we have these pioneers to thank.

Read more about the history of the Wah pedal here.